Here, I figure out why conceptual analysis failed and what concepts are really like.*

[ *Based on: “The Failure of Analysis and the Nature of Concepts,” pp. 51-76 in The Palgrave Handbook of Philosophical Methods, ed. Chris Daly (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).]

1. The Failure of Analysis

Philosophy began with attempts to define things. Socrates asked people “What is virtue?”, “What is justice?”, “What is knowledge?” Famously, he never found out.

Two millennia later, a movement arose in the English-speaking philosophical world known as “analytic philosophy”. At its inception, analytic philosophers thought that their main job was to analyze language or concepts. Many very smart, highly-educated people dedicated careers to the project of conceptual analysis in the 20th century. If ever we should have expected that project to bear fruit, it would have been in the 20th century.

What do we have to show for it? Only negative results—we refuted some analyses. We never found a single correct analysis. To speak more cautiously, as far as I can tell, no one—either in the 20th century or any other time—has ever advanced an analysis of any philosophically interesting concept that was widely accepted by philosophers as correct. Nearly all analyses are subject to counter-examples that most philosophers would agree refute the analysis. (Caveat: sometimes you will meet a philosopher who claims to have correctly analyzed some concept. But hardly ever do you meet one who thinks that anyone else has correctly analyzed a concept.)

( *The field of mathematics is an exception to the rule. It contains many precise definitions that are widely accepted by mathematicians. There may also be a few other concepts that can be defined. )

The attempts to define “knowledge” after 1963 are the most instructive case, because that term received particularly intense scrutiny. Philosophers went through dozens of increasingly complicated analyses and counter-examples over several decades, and no consensus emerged. To this day, we don’t know the definition of “knowledge”. Philosophers had similar experiences when they tried to define such things as “good”, “cause”, “if”, “freedom”, and so on.

This raises some questions:

What made people think that we could and should analyze concepts?

Why did it prove so difficult, and what does this tell us about the nature of concepts?

2. The Roots of Conceptual Analysis

a. Empiricism

The project of conceptual analysis was given motivation by the popularity of empiricism, which held that all knowledge must be either analytic or empirical (there is no synthetic a priori knowledge). Once you adopt that theory, you should next wonder what kind of knowledge philosophy itself might be producing. The 20th-century empiricists didn’t want to deny that they were producing knowledge, but they also couldn’t plausibly claim that they were producing empirical results (nor did they want to have to start doing observations and experiments). So they were almost forced to say that philosophy is all about analytic knowledge, which is knowledge that derives from the understanding of concepts, or of the meanings of words. So the job of philosophers must be to analyze concepts or words.

Fortunately, few people think that anymore.

b. The Lockean Theory of Concepts

Here is the important part. The drive for conceptual analysis comes from a very natural way of thinking about concepts and meanings, which is probably the way you’d think about them if no one told you differently. I call it the Lockean Theory of Concepts (but I don’t care whether this was really Locke’s view). It includes three elements:

1. Concepts are directly introspectible mental objects.

2. Most concepts are composed of other concepts.

3. The application of words is governed by definitions, which describe the composition of the concepts that a word expresses.

Notice two implications of this view:

(i) that most concepts should be definable. Apart from a few simple concepts, most concepts will be composed of other concepts. Since we can directly, introspectively observe our concepts, we should be able to describe how they are composed, and that would be to give a definition.

(ii) that definitions are useful, even necessary, to understand most words.

The history of philosophy, however, shows that this theory is wrong. If the Lockean Theory were true, we should have many successful analyses by now. Also, if the Lockean theory were true, the lack of analyses would prevent us from understanding and applying words. But in fact, we have approximately zero successful analyses, and this hasn’t stopped us from understanding and applying words.

3. An Intuitionist Theory of Concepts

Following is a better theory about concepts, which seems vaguely in line with some intuitionist views in ethics.

a. Properties and Natures

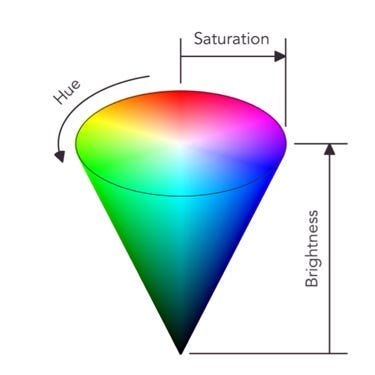

Every thing in the universe has a specific nature. This is a maximally specific, comprehensive property (or, the sum of all the properties of the thing). This would include, e.g., the exact shade of color of the object (or the exact distribution of colors throughout the object). The natures of things vary along numerous dimensions. We can imagine a space with those dimensions, the “quality space”: every particular thing occupies a point in the quality space. (You can also include dimensions for spatial locations and relational properties.) There could in principle be more than one thing at that point, but in practice, each ordinary object is the only thing that has its exact nature (other objects may be similar but we never find one exactly the same). The quality space is like the color cone (see image), but with dimensions for all other properties, not just colors.

There are also more general properties, such as redness, roundness, cathood. These are properties that many objects share. These can be thought of as regions in the quality space. Compare how the property redness is a roughly wedge-shaped region in the color cone.

Aside: This is a non-traditional way of thinking about properties. In the traditional view, one treats properties as primary and thinks of the natures of objects as conjunctions of their properties. I treat specific, determinate natures of things as primary, and think of properties as ranges of natures.

b. Concepts

When we form a concept, we are drawing a line (or a hypersurface, to be more pedantic) around a region in the quality space. Everything in that region is what the concept applies to.

How do we draw the boundaries of concepts? Many factors can influence this. We want concepts to be useful for conveying information in the world we live in. Hence, we tend to draw lines that wind up including a lot of things in the world. If there is a cluster of objects in a certain region of the quality space, we draw a line around that cluster. Had objects clustered differently, we would have drawn our conceptual schemes differently.

Example: Pluto used to be considered a “planet” when we thought there were 9 planets in the solar system. It was smaller than the other 8 planets, but that was okay. Later, astronomers discovered that there were 50 other objects in the solar system that were similar to Pluto and different from the other 8 “planets” (in a way similar to how Pluto differed from the other 8 planets). So we redrew our conceptual scheme to make the 8 big planets fit in one category (“planets”), and the 50 smaller things (including Pluto) another category (“planetoids”).

Conceptual boundaries also depend on practical interests. For instance, the category “bachelor” is of interest because humans are interested in who is eligible to marry a woman. That is why most people find the Pope to be, at best, a borderline case of a “bachelor”. He’s an unmarried man, sure, but he’s not quite a bachelor, because he’s not exactly marriageable.

Conceptual boundaries also drift over time. The etymology of most modern words shows them originating in words with completely different meanings. The meanings must have drifted through the quality space.

There are infinitely many regions in the quality space, so there are infinitely many possible concepts, though of course any human mind can only grasp finitely many concepts at a time.

c. Language & concepts

Most of our concepts are tied to language: we are prompted to form a concept by hearing a word in our language. We attempt to imitate how others are using that word, so each use we hear (while we are learning) influences our dispositions to apply that word. To “understand” the word is to have formed the right dispositions – i.e., to have become disposed to apply the word (or at least to sense that its application is appropriate) in approximately the same circumstances that people in your speech community apply it. Your understanding just consists of having those dispositions.

E.g., my grasp of the concept of knowledge consists of my ability to tell when it is appropriate to apply “knows” to someone’s mental state and when it isn’t.

4. Against Locke

Every element of the Lockean theory is deeply mistaken:

1. Concepts are not directly introspectible mental objects.

They are instead dispositional. Thus, the way to limn the contours of a concept is usually not to directly, introspectively examine that concept. The way is to activate your linguistic dispositions by imagining specific scenarios and observing your own disposition to find the application of a certain term appropriate or inappropriate.

2. Most concepts are not composed of other concepts.

They are constituted by dispositions that were formed by distinct sets of experiences. Each concept can have a unique boundary, which need not coincide for any distance with the boundary of any other concept. The boundaries can have complex, idiosyncratic shapes. This is why most concepts are indefinable.

3. The application of words is not governed by definitions.

It is governed by these dispositions that we spontaneously form after hearing others’ word usage and attempting to imitate it. We almost never learn words by hearing definitions; we almost always learn by seeing examples of the correct use of the word. This is why it does not matter that we don’t have definitions for most words; this does not stop us from learning and applying the words.

All this explains (i) why conceptual analysis failed in the 20th century, (ii) why we don’t need definitions, and (iii) why we evaluate definitions using particular examples. About point (iii), consider that we rejected the “justified, true belief” analysis of knowledge based on the Gettier examples, rather than applying the analysis to conclude that the Gettier examples are cases of knowledge. Nearly everyone instinctively found that the correct reaction.

It can still be useful to try to clarify concepts – e.g., by distinguishing a concept from others that it is often confused with, by drawing out some key conceptual relations (one concept implying another, etc.). What we don’t need and shouldn’t expect to do is to identify the exact necessary and sufficient conditions for the application of a given concept, using other concepts.

Hi Dr. Huemer, you said that to understand a word is to have formed the right dispositions to apply the word in approximately the same circumstances that people in one's speech community apply it. Wouldn't this suggest that AI language models understand the meaning of words? After all, Chat GPT has a strong disposition to use words in the same circumstances that people in the speech community apply them. Yet from what I've heard you say about the Chinese room thought experiment, AI language models don't have genuine linguistic understanding. So how would you resolve this tension?

How do your views on the resolution of the Sorites Paradox fit into this scheme? Would you say that heapness is a concept with fuzzy boundaries, or that the word “heap” ambiguously denotes many precise concepts?