1. Two Musical Masterpieces

As you know, Ludwig van Beethoven was among the greatest musical composers ever. For example, his Moonlight Sonata may be the most beautiful piano piece ever composed: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Tr0otuiQuU.

That version of it has 204 million views on YouTube. (My most-viewed video has 90k views, thus showing that Beethoven is ~2200 times greater than me. But I digress.)

Nevertheless, as wonderful as this piece is, it pales in comparison to what must be, judging by the numbers, the single greatest musical masterpiece ever to spring from the mind of man. I refer, of course, to the breathtaking “Baby Shark Dance”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XqZsoesa55w.

If you have not yet experienced the sheer joy of “Baby Shark”, you simply must follow the link to experience it for yourself. Any ten-second bit in the middle will do.

Doubtless you will immediately sense its greatness. Nevertheless, an interesting philosophical question arises: How do we know that “Baby Shark” is an artistic masterpiece?

One way we can tell this is that “Baby Shark” has been viewed over 13.6 billion times on YouTube, which is by far the most views of any of the hundreds of millions of videos posted on that platform. (Note: There are only 8 billion people on the planet.)

Still, though “Baby Shark” is clearly a work of genius, some might be skeptical about the assertion that it is greater than Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata. These are very different genres of music. Can they really be compared? And isn’t aesthetic value subjective anyway? Who is to say which of these is the greater artwork?

Well, me.

2. The Case for Baby Shark

a. Moral Value

Surely “Baby Shark” has brought more total enjoyment to the world than the Moonlight Sonata. Again, it has been viewed 13.6 billion times, which is about 13.4 billion times more than the Moonlight Sonata.

Granted, the Moonlight Sonata was also listened to for many years before “Baby Shark” was first composed, going all the way back to the beginning of the 19th century. But realistically, those listens aren’t going to make a big difference to the numbers. Anyway, clearly today Baby Shark is entertaining more people than Beethoven.

You might hypothesize that the Beethoven fans get more enjoyment per listen than the Baby Shark fans. But this really isn’t obvious; children can get quite excited about Baby Shark. Anyway, even if that’s true, it’s unlikely to outweigh the huge advantage that Baby Shark has in terms of sheer volume.

Enjoyment is good. So, prima facie, Baby Shark is morally better (better in terms of agent-neutral, objective value) than the Moonlight Sonata — unless there is some huge other advantage that Beethoven has over Baby Shark, which is hard to identify.

b. Artistic Merit

“What about artistic value?” you say. “Surely that’s the main thing here, and that’s different from moral value.”

Fair enough. It is easy to see that Baby Shark has great artistic value:

The purpose of art is to produce aesthetic pleasure.

Artistic value should be judged by reference to the purpose of art.

Baby Shark produces more aesthetic pleasure than the Moonlight Sonata.

Therefore, Baby Shark has greater artistic value than the Moonlight Sonata.

All of these premises seem true. Obviously, Baby Shark does not produce more pleasure than the Moonlight Sonata for all viewers. But it apparently produces pleasure for more viewers than the Moonlight Sonata. And this pleasure is evidently aesthetic (what else might it be? It’s not like it’s producing gustatory pleasure, or sexual pleasure, or the pleasure of gaining higher social status. It’s the pleasure of listening to a song, which is paradigmatically aesthetic.)

Since Baby Shark does better at the central purpose of art than the Moonlight Sonata, it is a better artwork.

3. Similar Cases

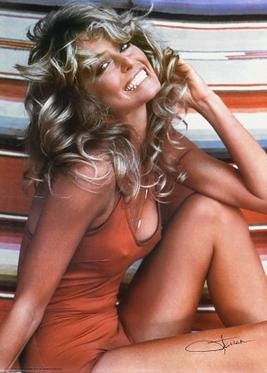

If the above reasoning is correct, there will be many other examples of modern masterpieces that far outpace the great works of the past. The Da Vinci Code easily beats Anna Karenina; Avatar far surpasses Casablanca; and the Farah Fawcett swimsuit poster beats the Mona Lisa.

4. The Puzzle

I have a deeply embarrassing confession, which many of you will have already guessed, given my previously-revealed inability to appreciate the genius of Shakespeare (https://fakenous.substack.com/p/the-emperors-new-art): I did not enjoy Baby Shark Dance. Yes, I know it is a masterpiece due to the argument given above, yet my dull, uncultivated sensibilities leave me unable to take the proper joy that I know others take in Pinkfong’s magnum opus. Indeed, when I first heard it, I was inclined to consider it auditory trash.

Hence, the puzzle: Why does it seem to many adults that such works as the Moonlight Sonata are “better” than the likes of Baby Shark? Ignorant shark-haters might be inclined rather to phrase the puzzle thus: In what way is the Moonlight Sonata better than Baby Shark?

5. Solutions

a. Excluding children’s art

Baby Shark is clearly meant for children and is mainly enjoyed by the young. Some might be inclined to dismiss the entire genre of children’s music as inferior to adults’ music for whatever reason. If you harbor this prejudice, simply take another example. The second most viewed video of all time is “Despacito”, which is also a music video, but one clearly meant for adults: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kJQP7kiw5Fk

It has been viewed 8.3 billion times (again, more than the number of people on the planet). This example would serve to raise the same puzzle.

b. Quality

Pleasurable experiences differ in both intensity and duration, both of which are aspects of quantity (the more intense the pleasure is, and the longer it lasts, the more total pleasure there is). But, according to John Stuart Mill, pleasures can also differ in “quality”. The pleasure of listening to a poetry reading, for example, is of higher quality than the pleasure of eating a tasty meal or having sex. So perhaps the aesthetic pleasure of the Moonlight Sonata is also of higher quality than that of Baby Shark.

I find this explanation insufficiently explanatory. As it stands, the explanation is too close to simply saying “the Moonlight Sonata is better”. Or rather, “the experience of listening to the Moonlight Sonata is better”. What makes it better? How do we know that it’s better?

Mill is often read as claiming that quality trumps quantity when it comes to pleasure, and that anyone who was familiar with both higher- and lower-quality pleasures would always prefer higher-quality ones over lower quality ones (which is how we know that they are indeed of higher quality). So, to make it concrete, I assume that Mill would prefer the pleasure of a good poetry reading over that of good sex.

I don’t think Mill’s preferences are as universal as he believes. Indeed, I think it would be a challenge to find any man outside of Victorian England who would side with Mill, however much they like poetry.

You can certainly identify descriptive differences between the pleasures called “lower quality” and those called “higher quality”. The “lower quality” pleasures are more fun, more boisterous, more universal, and less socially appropriate. But I don’t see that any of this makes them intrinsically worse.

c. Complexity

Baby Shark is a very simple piece of music, among the simplest that you can find. Perhaps that is also what makes it artistically inferior to most adult music.

But why would complexity be an artistic value? Does this mean that baroque art is pro tanto better than other styles? On the contrary, we often consider simplicity to be an aesthetic merit.

d. Qualified critics

Music experts prefer the Moonlight Sonata over Baby Shark. Maybe that’s what makes it better. (Compare David Hume’s view.)

One version of this view is that music experts judge that Moonlight > Shark. This runs into the Euthyphro dilemma: is Moonlight better than Shark because the qualified critics judge it better, or do they judge it better because it is better? Presumably it should be the latter. There is also a circularity problem if the qualified critics are understood as those who are good at appreciating good art.

So the best version of the view would probably be that good art is that which causes pleasure in the most sophisticated audiences, where this sophistication can be described in purely descriptive terms, without using aesthetically evaluative language. Perhaps the qualified audiences are those of high general intelligence, high sensitivity to the descriptive features of the art, and extensive experience in viewing (/hearing) art. Perhaps there are certain kinds of art that tend to produce the most pleasure in those audiences, and that is what we call “good art”. It is plausible that the Moonlight Sonata would be among these, while Baby Shark would not.

How would this view respond to the argument of section 2 above? I suppose it would reject premise 1, “The purpose of art is to produce aesthetic pleasure”, in favor of:

1*. The purpose of art is to produce aesthetic pleasure for smart people who consume a lot of art.

This seems a very elitist and parochial conception. Is that what we want to say?

If we met aliens who were much more intelligent than us, perhaps they would enjoy very different art than us. Would we then have to conclude that our “great” art wasn’t so great after all?

e. Robustness

Perhaps the aesthetic pleasure produced by good art is more robust than that produced by bad art. For instance, the pleasure of Baby Shark does not typically survive growing up. In the case of “Despacito”, perhaps one gets tired of it more easily than one grows tired of the Moonlight Sonata (assuming one can appreciate both to begin with). I’m not certain whether this is true, but it seems plausible.

This would give Moonlight a definite advantage over some of the more popular musical compositions, but it’s not clear that it outweighs the sheer quantity of enjoyment produced by the latter.

f. Beauty

A more plausible revision to premise 1 is:

1’. The purpose of art is to produce beauty.

The Moonlight Sonata is beautiful. Baby Shark, whatever else it might be, is not beautiful. So Moonlight is artistically better than Shark.

The problem is that 1’ doesn’t seem to be generally true. All or most great musical pieces are beautiful. However, many of what are considered good artworks are not beautiful and do not aim at beauty. For example, consider Picasso’s Guernica:

This is considered a great painting, but I don’t think you’d call it beautiful. Or take Salvador Dali’s The Persistence of Memory:

Again, it doesn’t seem to be aiming at beauty. (I choose these examples, rather than something like Rothko or Andy Warhol, because it would be too easy for you to just say the latter are bad artists, whereas I don’t think you’ll be inclined to say Picasso or Dali are bad artists.) If the purpose of art is to produce beauty, then which is a better artwork: Guernica, or Thomas Kincade’s The Village Lighthouse?

The latter is at least closer to being beautiful. But I don’t think anyone will consider it a better work of art.

6. Concluding Questions

What is the purpose of art? If the “best” art isn’t that which is most beautiful, and it isn’t that which produces the most pleasure, then why should we care about artistic value? In what sense is good art reliably better than bad art?

Perhaps the solution is a hybrid account of aesthetic value, like one sometimes sees in the literature on well-being, where aesthetic pleasure and some other objective value are jointly constitutive of the aesthetic good. So, even though baby shark yields more pleasure than Beethoven, the latter is also beautiful. The pleasure Beethoven's music yields is caused by/due to to its being beautiful. What great about art that isn't beautiful? It might be such that it produces aesthetic pleasure due its manifesting some other value like, say, understanding, wisdom, creativity, etc. If something like this is right we also have a pretty good way of explaining why so much contemporary art is just plain bad; namely, even if, ex hypothesi, such art manifests *some* value or other, it fails to produce aesthetic pleasure. Like, there's certainly something creative about many contemporary works, even if that creativity is often displayed in ways that are aesthetically displeasing.

I think part of the reason why there is so much subjectivity in aesthetics compared to ethics is because works of art take on a collective meaning from their observers/critics. As you implied, comparing Guernica and The Village Lighthouse as simply the works of art themselves ignores the context in which Picasso painted that piece which gives it a much deeper meaning about human suffering. Van Gogh comes to mind as well. Almost no one in his life saw the artistic value of his paintings that future people now line up around the block to see because his work is now understood within the tragic context of his life. It would be interesting to see what works of art people would enjoy the most if you took a bunch of people who somehow had never seen any famous art and had them collectively rank pieces solely on their aesthetic merits. I think the result would be that individual taste is much more subjective when removed from other factors like fame and artistic prestige.