1. The Emperor’s New Clothes

In Hans Christian Andersen’s famous tale, the vain Emperor buys a magnificent set of clothes from a pair of weavers, who inform him that these clothes are only visible to smart and competent people. He goes out in a great procession, showing off his new clothes to the public. The townspeople, who have also been informed of how these clothes work, hold forth about their beauty … until one child blurts out that the emperor is naked.

The story resonates because it illustrates real human tendencies:

The emperor and townsfolk are unsure of their own competence, so they are not sure if there really are clothes there. In case there are, they don’t want to reveal their own failings to others by admitting that they can’t see the clothes.

Even those who realize that the emperor is naked still don’t want to say anything because they don’t want to stand out from the crowd or contradict all of their fellows. (As in the Asch conformity experiment.)

The child naively blurts out the truth because he has not yet learned to fake reality like the adults.

2. The Vulnerability of Art

Many people suspect that the art world suffers from a similar problem. Perhaps a great deal of art is not as good as people say it is, or maybe isn’t good at all, and art people are just trying to trick us in the way that the swindlers tricked the Emperor.*

[*This idea is discussed (but not asserted) in Iskra Fileva, “Truth Without Taste” (ms.), from which the Kosinski example below derives.]

They tell us that these art works have great merit, but that only a person of refined taste can see it. When we fail to see it, we’re not sure if it’s not there or if we just lack refined taste. So we pretend to see it, and maybe we talk ourselves into thinking that we actually see it. In doing so, we create further social pressure for others to pretend to see the greatness of these artworks.

This story is far more likely than Anderson’s story, because art perception is highly subjective and can more plausibly be claimed to depend upon some special, difficult-to-detect capacity of “refined taste”.

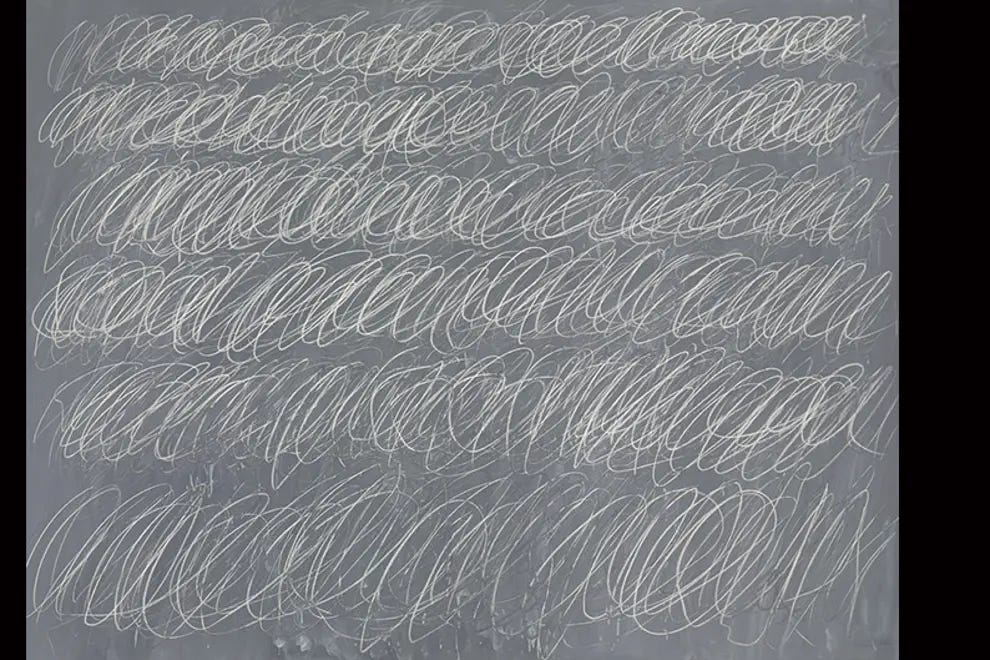

Cy Twombly

Before getting to any controversial cases, let’s start with one that you’re almost certainly going to agree with. Let’s start with the blackboard scribbles of the modern, abstract artist Cy Twombly:

That blackboard sold for $70 million.

I’m no art expert, but I call bullshit on that. If somebody tries to tell me that is a great artwork, I am going to find it vastly more probable that that person is bullshitting me than that that is actually great art. Indeed, I would go so far as to say the above image has about zero artistic value.

That is an existence proof for the “Emperor’s New Art” phenomenon. Now that we know this can happen, we can wonder how many other artworks have benefitted from it.

It would seem easier to trick people into thinking that a work with some aesthetic merit has a lot more merit than it really has, than to trick people into thinking that something with no merit is really great. So there probably are many more examples of works that have significant merit but are overrated than there are of Twombly-like nonsense masquerading as great art. If you can’t think of any overrated artists, that is most likely because you have been taken in by the emperor’s-new-clothes trick.

Casablanca

Casablanca is widely accepted as one of the greatest movies ever made. Around 1982, journalist Chuck Ross tried submitting the script of this iconic movie, with a different title and different author’s name, to 217 agencies to see if they would represent it. (http://www.tvweek.com/open-mic/2012/11/the-most-outrageous-experiment-even-conducted-in-the-movie-industry-do-those-working-in-the-movies-k/)

Of the 85 agencies who claimed to have read it, only 33 recognized it. (Another 8 thought it was similar to Casablanca.) Of those that did not recognize it, almost all rejected it on the merits. Only three wanted to represent it, plus another one who wanted to turn it into a novel. The rejecting studios gave many criticisms, especially of the supposedly excessive dialogue (which is actually the best aspect of the film).

This shows, again, that people’s perception of artistic quality is heavily influenced by what they know about the reputation of the art work.

Kosinski

Ross did a similar experiment with the manuscript of Jerzy Kosiński’s critically-acclaimed, award-winning novel Steps. When submitted under a different author’s name, the manuscript was rejected by all 14 publishers he submitted it to, including Random House, the actual publisher of the novel.

3. Shakespeare

Initial considerations

A few weeks ago, I quoted a short argument from Sam Bankman-Fried that claimed that the initial probability that the greatest writer was Shakespeare is very low. (SBF’s post) Many have ridiculed SBF for this, though most critics don’t seem to understand the argument. Anyway, Shakespeare is an excellent candidate for an overrated artist.

As SBF said, it would be surprising on its face that the greatest writer should have been born in the 1500’s, when (a) there were a lot fewer people in total than today, (b) people had much lower literacy, and (c) they had much less education.

It wouldn’t be at all surprising, though, that we would have a heavy bias toward the past.

People have a bias towards old things in other areas. E.g., if you ask who the greatest thinkers are in almost any area (unless it’s a new field, like computer science), people almost invariably name figures from long ago.

“Being the greatest writer” is not a property that you can just see. There is no proof of someone’s “greatness”. It’s a matter of highly subjective judgment, which is exactly the sort of thing that would be very easily influenced by bias.

Reputation feeds on itself. Very few people make completely autonomous judgments about merit. Each new generation learns from the previous generation what the “great” works are, then passes that on. Scholars want to discuss the figures who are already famous, not take a risk by talking about someone whom other people aren’t talking about. By doing this, they further increase the fame of the great figures. And so it goes. That is why the “greatest” figures tend to be from the distant past.

Other ways in which modern people should be advantaged with respect to writing potential:

People have a lot more leisure time for writing.

Many more people are buying books, thus creating a greater market for writers.

Modern writers have the benefit of looking at the great works of the past.

Given the interconnectedness of the modern world, modern writers have access to ideas from many different cultures.

They also have more ability to collaborate with or share ideas with artists all over the world.

Per the Flynn effect, IQ’s have gone up by about 30 points (2 standard deviations!) in the last century.

“It’s a curious pattern that whenever we have objective measures of something, the best performers are always from the recent past. This holds for running, darts, field goal kicking, weightlifting, memorizing the digits of pi, and chess. It’s only in subjective fields … that we see the supposedly ‘best’ performers being from long ago.” —Richard Hanania

From all this, if we hear a bunch of people saying that some dude in the 1500’s was the greatest writer ever and vastly superior to anyone today, it’s more likely that that is due to the bias toward the old and the already-famous, rather than that that person was really vastly better than anyone today.

Defenses of Shakespeare

Maybe great writing gets harder over time, because older writers have already picked the low-hanging fruit. That would make it unsurprising that the greatest writers should be in the distant past.

Reply: This is more plausible for natural science, in which there is a limited set of objective facts to discover. In creative endeavors, where there is an unlimited range of things to create, it’s more plausible that having access to more past works would make it easier for you to create great things.

Maybe Shakespeare is great because of his influence, rather than his intrinsic writing skill.

Reply: Okay, if you want to use the word “great” like that, sure; Shakespeare had a huge influence, perhaps the most of any writer. But I don’t think that’s all the Shakespeare-lovers mean. I think they actually believe his writing is either the best or close to the best that has ever existed in terms of its intrinsic aesthetic merits.

But we have to look at the work! We can’t just look at the prior probabilities or circumstantial considerations. And once we look at the work, we see that it’s amazing!

Okay, no. I looked at the work. That’s how I first learned that it was mediocre.

Admittedly, Shakespeare was an extremely skilled user of the English language. He was very skilled at doing some difficult things that I don’t care about:

He coined many catchy turns of phrase (“the green-eyed monster”, “Brevity is the soul of wit”, “All that glitters is not gold”, etc.) Why don’t I care about this? Because I’m assessing his work as art, and when I read his plays or poems, the fact that they contain catchy phrases that have become famous does very little for my aesthetic experience.

He wrote entire plays in iambic pentameter.

He wrote lots of sonnets, which are a type of poem governed by specific, arbitrary rules about length, rhyme scheme, and stress patterns. I also don’t care about these things.

Suppose you learned that there was someone who could write a play while standing on his head and juggling three fish. That’s very hard. Perhaps no one else in the world can do it. But that doesn’t mean those are good plays. I bet you wouldn’t go read them for that reason. (Compare the error of the labor theory of value.)

Likewise, the difficulty of writing a whole play in iambic pentameter doesn’t mean that is good. I’m not going to enjoy a play because of that.

But let’s get to the main things.

Characters

I had to read Hamlet, Macbeth, King Lear, and Romeo and Juliet in high school. I didn’t like any of the characters in any of them. People tell me that Shakespeare’s amazing works have universal appeal, but they didn’t speak to me at all. I could not empathize with any of these characters; I could not care what happened to any of them. I found most of them tawdry, uninteresting, venal. I don’t find it enjoyable to contemplate the deeds of such people. There are many works of literature with far more interesting and more developed characters.

Stories

I didn’t find any of his plays to be good stories, either. They have simple, often contrived and uninteresting plotlines. A man plots to kill the king in order to become king. Two lovers wind up killing themselves over a misunderstanding. I don’t see what’s so interesting about these events. Many novels have far more engaging, interesting, suspenseful, etc., stories.

SBF points out that, despite its reputation as the classic love story, Romeo and Juliet is a very low-quality, unrealistic, one-dimensional love story. There’s no development of their relationship, no subtlety; Romeo is in love seconds after seeing Juliet, with zero interaction. There are much deeper and more moving love stories in literature.

These elements – characters and plot – are not minor extras. They are the main things about a work of fiction. If you’ve got weak characters and plot, it doesn’t matter to me how great your language skill is. If I give you a cardboard sandwich, but I put some really nice garnish around it on a really fancy plate, that doesn’t make it a great meal.

Messages

I also didn’t find Shakespeare to have impressive ideas. An example is the famous “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day” sonnet, which advances the shallow and false thesis of the immortality of verse. (Poetry is not immortal. It merely sometimes lasts a little longer than a human life.) It also pretends that writing a poem that putatively addresses someone but provides no information at all about that person constitutes keeping that person alive in some meaningful sense. That’s also a silly idea.

Perhaps there are other great lessons to be learned from Shakespeare that I have missed (this is entirely possible, since I’m no Shakespeare scholar and only read a few works long ago). If so, someone please tell me some of those lessons.

Have you heard of the idea that the money paid for some artwork is money laundering? Clever if true.

Actually the main critique is that of a fact that books undergo natural selection just as animals in evolution

So if you know something from 1000 years ago and that’s something popular now, it must’ve been popular for centuries and centuries in a row thus greatly increasing probability of greatness aposteriori