Here, I explain why people are irrational about politics.*

[* Based on: “Why People Are Irrational About Politics,” in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics, ed. Jonathan Anomaly, Geoffrey Brennan, Michael Munger, and Geoffrey Sayre-McCord (Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 456-67. Originally posted as a web essay around 2002 (?). ]

1. The Puzzle of Political Disagreement

Disagreements about politics are widespread, frequently very strong (people on both sides are highly confident), and persistent (it’s almost impossible to persuade people). Most subjects are not like this. E.g., people don’t have such widespread, strong, and persistent disagreements about geology, or astronomy, or biology (unless politics or religion get involved). So, why is politics like this?

The fact that there is so much disagreement entails that people are very unreliable at getting to the truth about politics. So part of the question is: why are we so unreliable about this subject?

Here are some possible explanations:

Difficulty: The issues are really hard to figure out, so people just make understandable mistakes, like miscalculations.

Ignorance: We don’t have enough evidence to resolve the issues.

Divergent Values: Maybe people have conflicting fundamental values, and they adopt the political beliefs appropriate to their values.

Irrationality: We tend to be irrational when we think about politics.

#1-3 probably each contribute something to the problem. However, I think #4 is the main explanation.

2. Against Ignorance & Miscalculation

Ignorance and the difficulty of the issues fail to explain several key features of political disagreement:

a. Strength

If the issues are hard, or we lack evidence to resolve them, then people should have weak opinions, not really strong ones (unless we are irrational).

b. Persistence

We should also be able to persuade each other by giving each other more information, or (in the case of miscalculation) pointing out each other’s mistakes in reasoning … again, unless we’re irrational.

c. Correlations with Non-Cognitive Traits

You can guess people’s political views (at much better than chance reliability) by knowing non-cognitive facts about them, such as their gender, choice of occupation (where this occupation doesn’t expose them to relevant political evidence), aesthetic tastes, and (non-cognitive) personality traits.

d. Clustering of Political Beliefs

You can guess someone’s views on one political issue by knowing their views on other, completely orthogonal issues. E.g., guessing someone’s view on abortion from their view on gun control.

What explains all this?

3. Divergent Values

The divergent values theory fails to explain:

a. Clustering

Divergent values don’t explain why views about logically unrelated issues correlate. In some cases, the correlations are the opposite of what you’d expect. E.g., you would expect that people who think fetuses have rights would be more likely to think animals have rights (because they have more liberal views of the criteria for rights).

b. Why values diverge

The theory just explains one kind of disagreement by another kind of disagreement.

You could try to explain values divergence by, say, appealing to an anti-realist theory of ethics. For the problems with anti-realism, see my book, Ethical Intuitionism. In addition, this approach implies that there are no facts about the correct political positions. But that then makes it weird that people argue about them as if there were such facts (each treats their own position as objectively correct).

c. Non-values disagreements

Many, perhaps most, political disagreements concern descriptive facts, not values. E.g., in the gun control debate, almost all the discussion is about such factual questions as whether gun control laws work and whether guns prevent tyrannical government. In the present debates about Trump vs. Biden, people disagree about such things as whether either candidate committed election fraud in 2020, whether either candidate is suffering from dementia, whether either is going to weaken America, etc.

4. Rational Ignorance & Irrationality

According to economists, many voters have rational ignorance about political issues: they are uninformed because collecting political information would take time and effort, which is a cost, and that cost outweighs the expected benefits to them. This is partly because most individuals realize that they have close to zero chance of ever actually changing public policy; therefore, the expected benefits to them of having correct political views are close to zero.

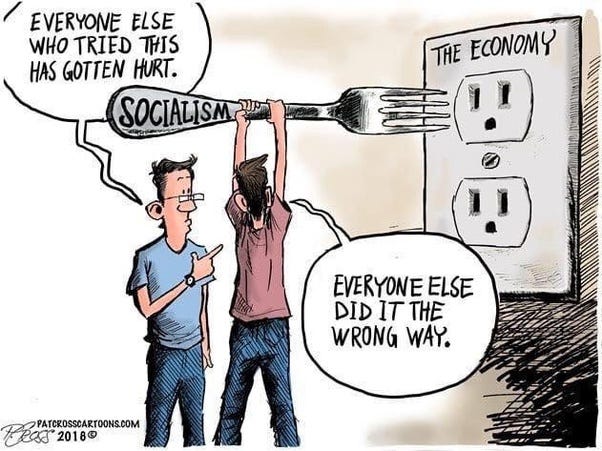

A parallel theory explains why most people also think irrationally about politics. Thinking rationally has costs: it requires effort, and it often results in being unable to believe what you want to believe. Most people, again, realize that they have almost no chance of changing public policy, so the expected benefits to them of having correct political beliefs are near zero. So the “cost” of being rational about politics tends to outweigh the expected benefits. (See The Myth of the Rational Voter.)

Note that there are two notions of “rationality” in play here. The theory just described assumes that people tend to instrumentally rational (roughly, they tend to do the things that get them what they want), and it uses that to explain why, in some cases, they are epistemically irrational (they form beliefs in a way that isn’t truth-directed, they commit logical errors, etc.).

This theory assumes (i) that people have things they want to believe (apart from wanting to believe the truth or what is supported by the evidence), and (ii) that people can control their beliefs. Let’s discuss those things.

5. What We Want to Believe

We don’t just always want to believe what’s objectively true. Here are some influences on our belief preferences:

a. Self-centered bias

We might want to believe things that serve our own interests, or (more commonly, I think) things that appear to serve the interests of groups that we favor. For instance, if you want to be “on the side of” blacks in America, then you might want to believe that affirmative action.

b. Self-image

Political beliefs can help us portray ourselves (both to ourselves and to others) as a certain kind of person. E.g., if you want to portray yourself as nice, you support more social welfare programs; if you want to seem patriotic, you support more military spending.

c. Social bonding

People like to fit in with particular social groups, and you may have to adopt particular political beliefs to do that. If all your friends are highly progressive, you’ll have psychological pressure to hold progressive views.

d. Coherence

People like to believe that all important considerations point in the same direction on a political issue; they don’t like to admit that difficult tradeoffs have to be made. Thus, we’ll either believe (i) that capital punishment is just and an effective deterrent, and hardly anyone is wrongly convicted, or (ii) that capital punishment is unjust and not an effective deterrent, and many people are wrongly convicted. It’s hard to find people who hold “conflicting” views in the sense of finding different considerations pointing in opposite directions. But of course, reality isn’t so convenient: in reality, different considerations point in opposite directions all the time.

These things explain why people would often want to hold certain political positions, independently of whether those positions were correct or supported by the evidence.

6. How We Control Our Beliefs

Some philosophers claim that a person cannot control their beliefs. For example, you can’t just decide to believe that you’re a giraffe, given that you can just see that you’re not one.

Here are some ways that we can control our beliefs:

a. Biased weighting of evidence

We can’t just believe something that we have no evidence for and conclusive evidence against. But if there is a lot of mixed evidence, we can attach a little more weight to the pieces of evidence that support what we want to believe, and less to the evidence on the other side, than is objectively justified.

b. Selective attention and energy

We can decide to spend time thinking about the arguments on one side of an issue. We can try to think of reasons in favor of a view, and not try to think of any objections. If we hear an objection, we can try to think of responses to it, and not try to think of any responses to our responses.

c. Selection of evidence sources

We can gather information from sources who agree with us politically, and not listen to the sources with conflicting political views. Practically everyone (who is engaged with politics) does this, practically all the time.

d. Subjective, speculative, and anecdotal arguments

We can rely on arguments that turn on subjective judgment calls, arguments that call for speculation about things we don’t have conclusive evidence for, and arguments based on a few specific examples (which have been chosen by us) rather than statistics. All of these kinds of reasoning are very susceptible to bias, so they are a great way of getting yourself to believe what you want to believe.

If a person is very clever, they can come up with ways of maintaining the beliefs they want to hold in the face of almost any evidence or counter-arguments. This is why it is almost impossible to convince an academic to change his political views.

7. What Should We Do?

The problem of irrationality is the worst social problem, because it is the problem that prevents us from solving all the other problems. If we’re forming beliefs irrationally, it would be sheer luck if we actually fixed our problems. (Compare: what if your doctor was deciding what medical treatments to give you based on his emotional reactions, his self-interest, his desire to bond with some social group, etc.? His care would almost certainly make you worse off.)

The solution starts with making people aware of the problem, because it’s harder to form beliefs irrationally once you’re aware of the ways in which you might be doing that. Irrationality typically involves some degree of hiding what you’re doing from yourself. More specifically, we should try to identify the subjects on which we are especially likely to be biased, e.g., topics on which we have strong emotional reactions, topics on which the social group we want to belong to has strong views, etc. (see sec. 5 above).

The other key move is to make an effort to avoid engaging the mechanisms for controlling beliefs listed in sec. 6 above. When you have a political belief, or any controversial belief, you make an effort to think of objections to that belief. You should try to collect evidence from a variety of (reliable) sources with different perspectives. And you should try to avoid relying overly on subjective, speculative, and anecdotal arguments.

Bear in mind that people in general tend to be highly unreliable about politics, it’s unlikely that you’re a radical exception to this, so you should be open to the possibility that you’ve made a mistake, especially with controversial beliefs. If many smart people disagree with you, it is likely that there are some rational reasons for the other side. (This isn’t guaranteed to be true, but it is usually true.) So if you regularly fail to see how anyone could possibly hold the opposite view on political issues, and those people regularly seem to you either evil or idiotic, be advised that the most likely explanation for this is that you are dogmatic.

You should read The Myth of Left and Right (or watch a YouTube video about it) by the Lewis brothers, Hyrum (a historian) and Verlan (a political scientist). They offer much evidence to support the claim that the clusters of beliefs concerning political issues accepted by self-identified leftists (e.g., liberals/progressives) and rightists (e.g., conservatives) vary with time and place. Also, those belief systems are internally contradictory. So, neither side can be right about everything even though they assume they are and that their ideological opponents are wrong about everything.

In order for a complete political philosophy to be objectively correct, it must be both internally and externally consistent. To be externally consistent, no proposition within the system of propositions that constitute the philosophy can contradict any true proposition outside the system in any other field of knowledge. It's logically impossible for there to be more than one political philosophy that's both internally and externally consistent. I suspect we both have a pretty good idea about which political philosophy is both internally and externally consistent. Any inconsistent political philosophy can be destroyed by classical logic's principle of explosion.

I'm certain that it's impossible for there to be more than one political philosophy that's both internally and externally consistent. That's not the same as saying that there is exactly one such political philosophy, since that doesn't rule out the possibility that there is no such philosophy. However, for various reasons too long to explain here, I believe there is such a political philosophy. The most likely candidate of those I've checked is pure libertarianism. According to Bryan Caplan, a pure libertarian would get a score of 160 points (the highest possible score) on his Libertarian Purity Test, which you can find online. To get a score of 160, one would have to be an anarcho-capitalist. An anarcho-capitalist society is not a political democracy.

The Nolan Chart, which you can find online, is divided into five sections each of which shows one of five political positions commonly accepted by Americans: libertarianism, authoritarianism, liberalism (progressivism), conservatism, and centrism. I have arguments that seem to prove that only one of those positions is internally consistent: pure libertarianism, which appears in a corner of the libertarian section of the chart. All other positions on the chart, including impure versions of libertarianism are internally contradictory. Except for pure libertarianism at one corner of the chart and pure totalitarianism at the opposite corner in the authoritarian section, all positions are inconsistent mixtures of libertarianism and authoritarianism. Since pure totalitarianism is directly opposed to pure libertarianism, you might expect it, too, to be logically consistent. Surprisingly, it is not. That's because in a purely totalitarian society whatever is not prohibited is required. But the ruler of one purely totalitarian society could prohibit the same things the ruler of another requires so that the two rulers could disagree on every issue. Hence, pure totalitarianism is internally inconsistent.

As stated above, the Nolan Chart shows political positions commonly accepted by Americans. It has no sections for other possible political ideologies. To get an idea of what other ideologies are possible, see various versions of the Political Compass online. I haven't checked all those other ideologies. Perhaps there's some political philosophy besides pure libertarianism that's internally consistent. Suppose there is exactly one such philosophy. In that case, the correct political philosophy would be whichever of the two is externally consistent, and it would be rational to accept that political philosophy, which may be the alternative to pure libertarianism. However, there is a reason to believe that pure libertarianism is externally consistent: One of its basic principles appears to be a necessary truth. If it is, then pure libertarianism is externally consistent because every true proposition must be consistent with a necessary truth. Having said all this, there's a pretty good chance I've made some mistakes in my reasoning.