Here, I critically assess Larry Temkin’s book, Rethinking the Good.*

[ *Based on: “Transitivity, Comparative Value, and the Methods of Ethics,” Ethics 123 (2013): 318-45. Ethics invited me to do this long review essay about the book. I accepted because, hey, publication in Ethics! ]

1. The Case Against Transitivity

Most of the book is about objections to the following principle:

Transitivity: If x is better than y, and y is better than z, then x is better than z.

For brevity, I will here include just a few of the alleged counter-examples to Transitivity that Temkin mentions.

1.1. Rachels’ Counterexamples

First, there is a type of example first devised by Stuart Rachels (see “Counterexamples to the Transitivity of Better Than”). Imagine a series of experiences, E1, E2, . . . E100.

E1 is a year of the most horrific torture imaginable.

E2 is two years of slightly less intense torture.

E3 is four years of slightly less intense suffering than E2.

… and so on. This continues to …

E100, which is 2^99 years of barely noticeable discomfort.

Most people judge that E2 is worse than E1 (for it is twice as long and only slightly less painful), that E3 is similarly worse than E2, and so on, all the way to E100, which is worse than E99.

However, most people also intuit that E1 is worse than E100. Hence, it looks like a counterexample to Transitivity. There is a similar example involving pleasure.

1.2. Dispersing Burdens

Suppose there are 1010 people, P1, P2, … , P1010. You are given a choice between inflicting 1000 days of pain on P1 and inflicting just 1 day of pain on each of {P1,…,P1010}. Most people think it’s better to inflict the pain on the 1010 people (even though there will be slightly more person-days of pain, it seems better to spread the burden among a wider group).

Next, you can choose between inflicting 1000 days of pain on P2 and inflicting 1 day on {P1, …, P1010}. Again, it seems better to spread the burden.

We continue this way until you reach P1000. Each time, it seems as if you choose the better option by spreading the pain among the 1,010 victims. However, at the end, you will have inflicted 1000 days of pain on 1010 victims. If instead you had chosen to concentrate the pain on a single victim, you’d have 1000 days of pain inflicted on only 1000 victims, which is clearly less bad than the same pain inflicted on 1010 victims.

(Assume each day of pain is equally unpleasant in all cases.)

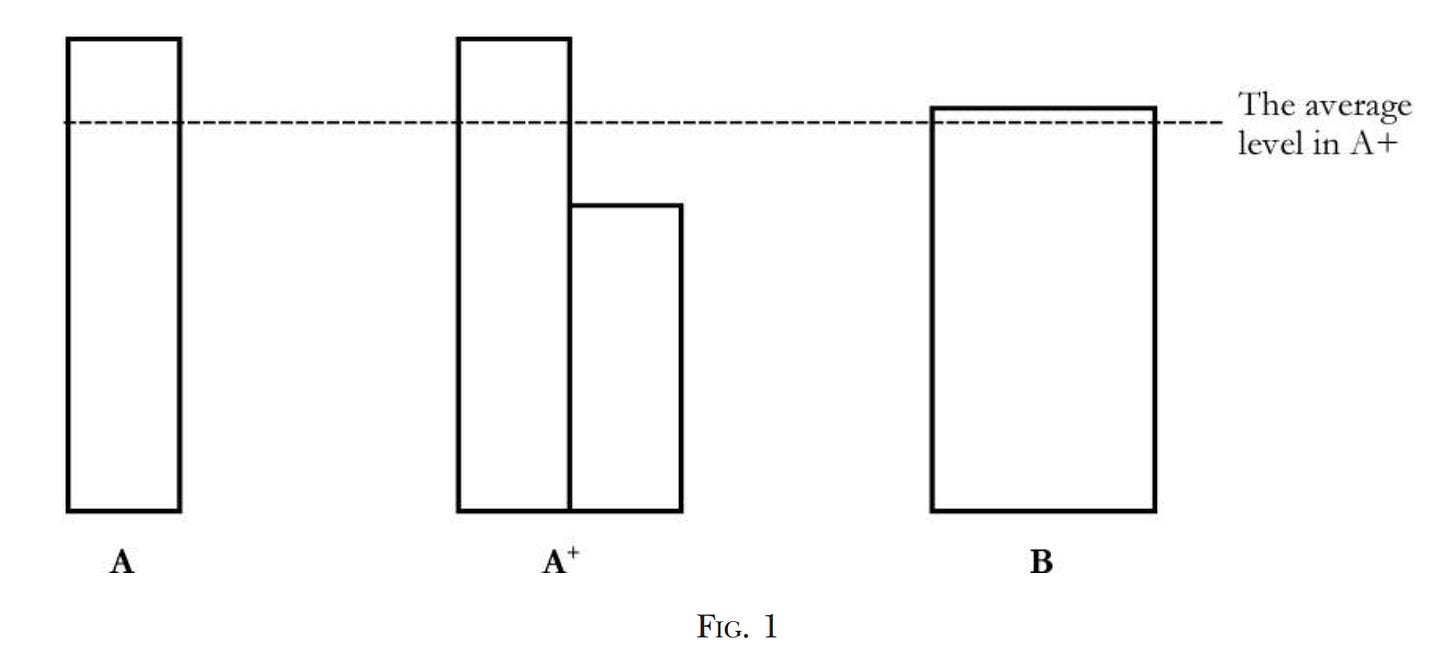

1.3. The Repugnant Conclusion

Derek Parfit discovered (but did not endorse) the following amazing argument. Imagine a world containing, say, a billion people with wonderful lives (see fig. 1 below. The width of each bar represents a population size, while the height represents a level of well-being). Call that world A. Now imagine adding another billion people to A who would have slightly less-good lives. Call this new world A+. It seems that adding these new happy people to the world (while leaving the original people equally well-off) cannot make the world worse, so A+ must be at least as good as A.

Next, imagine taking all the people in A+ and equalizing their welfare, while also adding a small amount to everyone’s well-being, leaving them with a higher average welfare than A+, but lower than the average in A. Call the result world B. It seems that B is better than A+.

By Transitivity, it follows that B is better than A.

Now you can repeat this kind of reasoning to show that world C is better than B, where C is a world with twice the population of B and slightly lower average welfare. And so on. This continues down to world Z, which has an enormous population of people with lives just barely worth living.

By Transitivity, you can ultimately conclude that Z is better than A. This is the “Repugnant Conclusion”, which many people find highly counter-intuitive. (But for defense of it, see https://philpapers.org/archive/HUEIDO.pdf.) Temkin proposes to avoid it by rejecting Transitivity.

1.4. The Theory Behind Intransitivity

If “better than” means “has a higher degree of goodness than”, then it would seem that betterness must be transitive, just because the “greater than” relation in arithmetic is transitive.

But maybe that’s wrong. Temkin proposes that goodness is essentially comparative, meaning that the degree of goodness that something has depends on what alternatives it is being compared to. So, in the pain example (1.1 above), maybe how good E1 is depends on what we’re comparing it to. If you’re comparing E1 to E2, then E1 is not as bad as it is when you’re comparing E1 to E100. This could be because in the first comparison, duration is highly relevant, but in the latter comparison, duration is less significant while intensity of pain is more important.

2. In Defense of Transitivity

That gives an indication of the case against transitivity. So why do I still endorse Transitivity?

2.1. Intuition

Nearly everyone has an extremely strong, firm intuition that better-than is transitive. People with radically different other beliefs tend to agree on this. Indeed, this may be the most intuitive principle in all of ethics.

2.2. Is Transitivity Analytic?

Temkin denies that Transitivity is analytic because he says that the Essentially Comparative View of value is coherent (he hasn’t contradicted himself in stating it).

However, I think Transitivity is analytic. This is because I believe (i) that “x is better than y” just means “x has a higher degree of goodness than y”, and (ii) that a thing’s degree of goodness is a monadic property of that thing, not a relation between the thing and something else. (Of course, betterness is a relation, but I don’t understand the idea that degree of goodness itself is a relation.)

(i) is a semantic point, and (ii) is a logical point. They together imply Transitivity. Conclusions that are true in virtue of semantics and logic are analytic. So I think Transitivity is analytic.

There could of course be a concept that works the way Temkin describes. But, on introspection, I do not think that “goodness” is such a concept, nor do I think I possess any such concept.

2.3. The Money Pump Argument

Suppose there are three things, A, B, and C, where A > B > C > A (where “>” represents betterness). You presently have A, and I have B and C.

I offer to let you pay a small amount of money to be allowed to trade A for C. Since C>A, you accept.

I then let you pay a small amount of money to trade C for B. Since B>C, you again accept.

Then I let you pay a small amount of money to trade B for A. Since A>B, you accept.

Now you’re back to what you started with, only with less money.

This is widely taken to show that you have made a mistake. The three trades each seem rational given the evaluative judgments listed above. So the most plausible account of the mistake is that it was a mistake to think that C>A, or that B>C, or that A>B. I.e., the most plausible account is that there can’t be an intransitive betterness ranking.

2.4. The Dominance Argument

Go back to the pain example from sec. 1.1. Imagine that you had to choose between getting all of the even-numbered pains, and getting all of the odd-numbered pains. I.e., you have to choose between [E1+E3+…+E99] and [E2+E4+…+E100]. Which is better?

First, it seems that the even-numbered collection is worse. For suppose you started out with [E1+E3+…+E99]. You could convert to the other collection by making every one of the component pains worse — i.e., by trading E1 for E2, E3 for E4, and so on, up to trading E99 for E100. According to Rachels and Temkin, each one of these trades is a worsening. So it seems that the whole collection, [E2+E4+…+E100], is worse than [E1+E3+…+E99].

But wait. No, it seems that the odd-numbered collection is worse. For suppose you started out with the even-numbered pains, slightly rearranged: [E100+E2+E4+…+E98]. You could convert it to the odd-numbered collection by making every component worse: trading E100 for E1, E2 for E3, and so on, all the way up to trading E98 for E99. According to Rachels and Temkin, each of these trades is a worsening. So the whole collection, [E1+E3+…+E99], must be worse than [E100+E2+E4+…+E98].

But this can’t be. [E2+E4+…+E100] is the same collection as [E100+E2+E4+…+E98]. This collection cannot be both better and worse than [E1+E3+…+E99].

The most likely explanation of what went wrong is the assumption that E1 is worse than E100. If you remove that (and hence remove the intranstivity) then there’s no problem: The even-numbered collection [E2…E100] is unambiguously worse.

3. An Error Theory: The Attraction/Aversion Heuristic

We often make evaluations using the Attraction/Aversion (AA) Heuristic: we rely on the degree of emotional attraction or aversion that we feel when contemplating a possible outcome, to judge how good or bad the outcome is. So if you feel more aversion when thinking about x than when thinking about y, you’ll judge x as worse than y.

It is very plausible on its face that this heuristic would systematically lead us astray in certain kinds of cases. Humans tend to do poorly at appreciating large quantities. In particular, as the quantity of something (emotionally significant) increases, our emotional reaction to it will increase less than proportionally. This is especially true for very large quantities; there is, after all, a limit to how much aversion you can feel.

This could be expected independent of what the objective, evaluative facts are. E.g., even if a billion years of pain is 1,000 times worse than a million years of pain, people would not have emotional reactions to the former that are anything like 1,000 times as intense as our emotional reaction to the latter. So the AA heuristic would lead to systematically underappreciating the badness of long periods of pain.

The same goes for large numbers of people. Even if a billion lives were 1,000 times more valuable than a million lives, we should not expect human emotional reactions to the former to be 1,000 times stronger than to the latter. So the AA heuristic would lead to systematically undervaluing large populations of people.

This explains why the intuitions about the cases in section 1 should be distrusted.

4. The Capped Model for Ideals

Temkin mentions another way of avoiding the Repugnant Conclusion (without rejecting Transitivity). We could hold that there is a limit to how much value can be gained by utility (so there would be diminishing marginal moral value to utility).

4.1. Single Cap for Utility

On one view, there is a single cap for utility, and then different caps for other ideals (such as the value of equality). This has implausible implications. See Figure 2.

World E (for “equal”) is one with a very large population of people all at the same low welfare level. World U (for “unequal”) has the same large population of people, but with all different utility levels. The lowest level of anyone in U is equal to the level of the people in E; everyone else in U has higher utility (so U is Pareto superior to E).

The theory we’re considering implies that U is worse than E. Both are close to the cap for utility due to the very large population, but world E has, in addition, the value of equality.

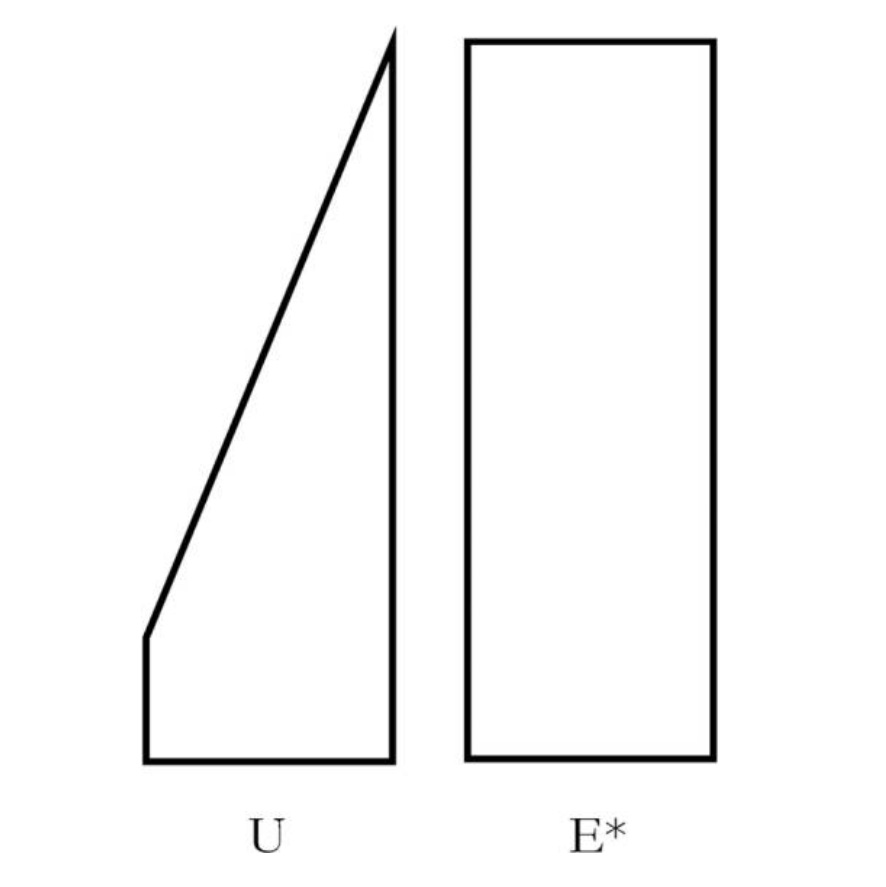

4.2. Multiple Utility Caps

On another view, there are different caps for different kinds or levels of utility. So maybe there is a cap to the value attributable to low-utility lives, and a different cap to the value for high-utility lives (and maybe more caps for other degrees or kinds). This could explain why world Z from sec. 1.3 above cannot exceed the value of world A, no matter how big the population of Z is.

Now consider worlds U and E* in figure 3.

U is as before. E* is a world with the same population as U, but in which everyone is raised to the welfare level of the best off person in U.

The theory we’re now considering implies that U is better than E*. For E* will get close to the cap for the value of high-utility lives. But U, due to its large population, will get close to the cap for high-utility lives and close to the cap for low-utility lives, etc., thus giving U higher total value.

4.3. The Egyptology Objection

All forms of the capped model for ideals imply that research in Egyptology can be relevant to your decision whether to have children. For they imply that how valuable your child’s life would be depends on how numerous and how well-off other people in the world (including, e.g., the ancient Egyptians) have been.

5. Rethinking Ethical Theorizing

The problem isn’t that Temkin and others (Rachels, Parfit, etc.) are relying too much on intuitions; all ethical theorizing is 100% based on intuitions. The problem is that they are relying too much on the attraction/aversion heuristic, and not enough on purely intellectual intuitions deriving from non-emotional thinking about how value ought to work. Temkin et al. thus end up making theoretically unnatural, ad hoc posits to rationalize emotionally-based intuitions about cases.

Transitivity is a good example of a purely intellectual intuition. Another is the intuition that if one world is Pareto superior to another, then it is overall better. We should trust these intuitions over those arising from our sentiments of attraction or aversion to descriptions of possible scenarios.

The problem isn't transitivity (where A > B and B > C implies A > C), the problem is the continuum of many, many functions which are all assumed to be true (where Ni > Ni+1).

To see this most clearly is via the Sorites paradox - I explain the parallel here:

https://ramblingafter.substack.com/p/the-repugnant-conclusion-messed-with

The dispersing burdens example (section 1.2) is given as a supposed counterexample to transitivity, but it strikes me it has a better use.

Let’s label the decision to disperse Pi’s pain to everyone as Ai, and the decision not to disperse it as Bi. The claim is that each Ai is better than each Bi, but that the collection of all Ai from 1 to 1000 is worse than the collection of all Bi from 1 to 1000. If we accept those better-than claims, then we have a counterexample to the dominance principle (section 2.4): [A1, A2, …, A1000] and [B1, B2, …, B1000].

To avoid the counterexample, you need to argue that Ai is actually worse than Bi. Taking the count of person-days of pain as the measure of the badness gives you the desired result (1010 for Ai, 1000 for Bi), but is it a reasonable thing to do? I’d say not. The badness of 1000 consecutive days of pain is clearly worse than the badness of 1000 days spread thru (say) 80 years – about one day of pain a month. It’s possible to take one day a month off from the day-to-day without seriously impacting your life. Taking three years off is going to mess up your life. Spreading those person-days over people instead of over days has a similar benefit: no one’s life gets seriously messed up.

My error theory for thinking that the person-days of pain is a good measure of the badness is that people think that the badness can be modelled with a number. That works great for comparing badnesses (just compare the numbers), but fails horribly when it comes to measuring cumulative badness. It pumps the intuition that the badness of two or three bad things is just the sum of their individual badnesses. Our intuitions say otherwise.

The same error is seen in the argument for the repugnant conclusion (section 1.3). We are adding well-being in going from A to A+, and again going from A+ to B. The “numbers” keep going up as we move on to worlds C and D and all the way to Z. Yet Z is clearly worse than A. Supposedly the problem has to be solved by getting rid of transitivity, but it’d be better to recognize that the mapping of goodness to numbers is the problem. We have no good reason to believe that B is better than A, in spite of the good argument that the numbers must be going up.

I want to point out that I am not arguing against transitivity here. I have no reason to believe that the “betterness” that people are interested in is intransitive, in spite of the fact that we can create artificial “betterness” relations that are intransitive: rock is better than scissors which is better than paper which is better than rock. All I’m saying is that the idea that we can model betterness using Real numbers is faulty. It’s a partial order. Model it using another partial order. Maybe just assume it’s a lattice. Transitivity, check! Additivity? Not generally.