The Virtues of Direct Realism

Here, I explain the virtues of a direct realist account of perceptual knowledge.*

[ *Based on: “The Virtues of Direct Realism,” pp. 95-112 in Direct Versus Indirect Realism: A Neurophilosophical Debate on Consciousness, ed. John Smythies and Robert French (London: Elsevier, 2018). I contributed this paper to a volume dedicated to debating direct vs. indirect realism. My replies to other authors (same volume): pp. 194-200, 259-67. ]

1. Epistemological Direct & Indirect Realism

Note: There are many “direct realism” straw men that people like to attack. Most “indirect realists” appear to have no idea what direct realists actually think. This appears to be because they have not taken the time to simply read a direct realist’s definition of the view.

For present purposes, I’m interested in the epistemological issue, viz. that between “epistemological direct realism” and “epistemological indirect realism”:

Indirect Realism: The view that our justification for contingent, external-world beliefs always depends upon our having justification for some other beliefs, which concern mind-dependent entities (variously called “perceptions”, “sense data”, “ideas”, or states of “being appeared to”).

Direct Realism: The view that perception gives us justification for contingent, external-world beliefs that does not depend on having justification for any other beliefs.

Notes:

Direct realists needn’t deny that mind-dependent states called “perceptions” exist.

Nor need they deny that we can have justified beliefs about them.

They just deny that our justification for beliefs about the physical world depends on justification for beliefs about mind-dependent things.

2. A Version of DR

Phenomenal Conservatism

My general view of justification is phenomenal conservatism: You have (at least some) justification for believing what appears to you to be the case, as long as you have no specific reasons to doubt the appearance.

This applies to all kinds of beliefs, including perceptual, introspective, memory, and intuitive beliefs. Inferential justification is also explained by a special kind of appearance called an “inferential appearance”. Btw, when you have “grounds to doubt” an appearance, those grounds come from other appearances.

I won’t here repeat all the reasons in favor of this theory of justification; see my other writings.

The Justification of Perceptual Beliefs

Perceptual experiences are a kind of appearance. So, as long as you have no reason to doubt your perception, you have justification for believing what thus appears to you to be the case.

During normal perception, what appears to you to be the case is some external world proposition, not a proposition about your mind. E.g., when you see a cat on your pillow, what appears to you is something like this:

[There is a cat on a pillow.]

i.e., that is the content of your mental state. The content of the appearance (what appears to be the case) is not:

[There is a sense datum of a cat on a pillow.]

(I take this to be obvious.) Therefore, what you become justified in believing is [There is a cat on a pillow], not merely [There is a sense datum of a cat on a pillow].

This is a kind of foundational justification. It depends only on your having the perceptual experience of the cat on the pillow. It does not depend on your having justification for believing [There is a sense datum of a cat on a pillow] or anything like that.

So direct realism is correct.

Conceptual content of perception

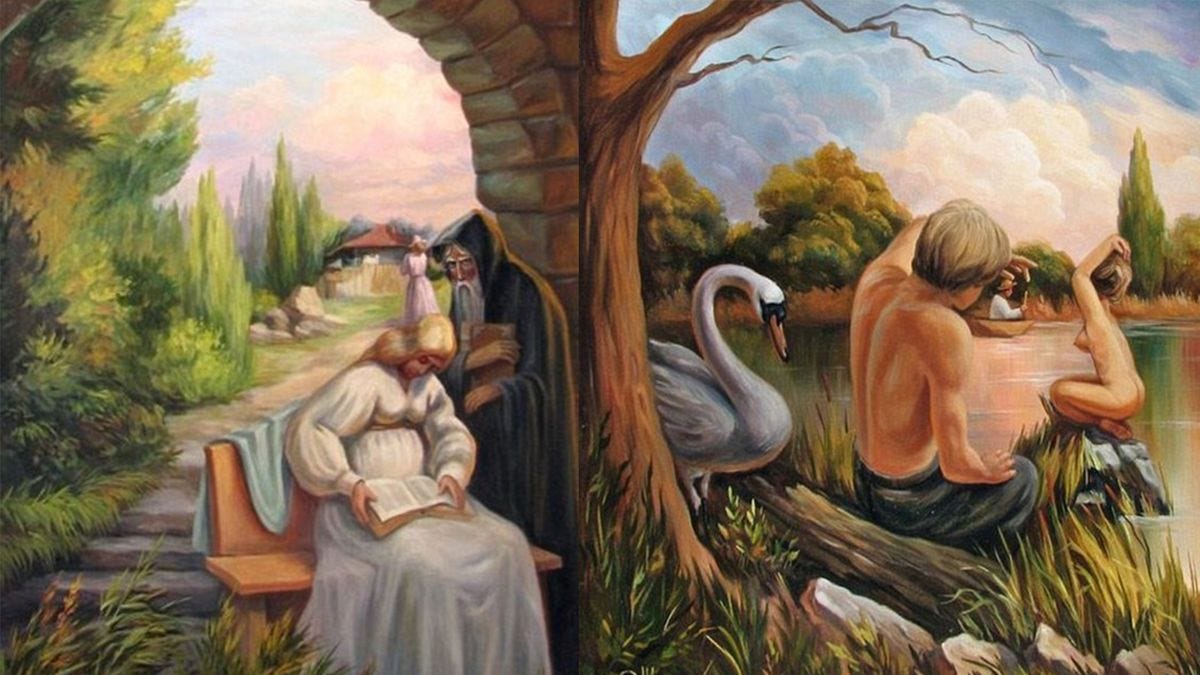

Many people have noticed that our background concepts can affect our perceptual experiences. E.g., look at the famous duck-rabbit picture below.

If you know what a duck is and what a rabbit is, then you will be able to perceive both aspects of the image. If you lack one concept or the other, you will be unable to see the corresponding interpretation of the image. This shows that background concepts and experience affect the character of our current perceptual experiences.

I mention this just to note that all this is perfectly compatible with direct realism. Again, DR (for present purposes) just says that your perceptual experiences give you non-inferential justification for at least some external-world beliefs. It doesn’t say that past experiences or background concepts can never affect your experiences.

3. The Basing Problem

The IR’ist Case for an External World

The indirect realists have to explain how we could get from propositions about mental states (“sense data”, “ideas”, etc.) to propositions about the physical world. The most popular answer to this is an inference to the best explanation: the best explanation for why you have the sensory experiences you do is that there is a real, mind-independent physical world, and you are veridically perceiving parts of it.

The IR’ist then has to explain why this is better than alternative explanations, such as that you’re a brain in a vat, or there’s a deceiving god, or you’re living in a simulation. This is a far from trivial task, though some philosophers (after much contemplation and argumentation) have come up with some ways that the Real World Hypothesis might be better than things like the Brain-in-a-Vat Hypothesis.

The Basing Problem

The basing condition for knowledge is widely acknowledged: In order for a belief to be justified, it must actually be based on good reasons. If you have good reasons for P available, but they form no part of why you actually believe that P and you instead based your belief on some bad reasons, then your belief counts as unjustified.

The problem is that ordinary people do not in fact base their external-world beliefs on an inference to the best explanation. No normal person contemplates different explanations for his sensory experiences then figures out reasons why the BIV hypothesis is inferior to the RWH, etc. Very few people would even have any idea how to do that. So, according to the Indirect Realists, our external world beliefs must be unjustified. So no one knows anything about physical reality, except perhaps a few philosophers. This is super-implausible.

4. The Symmetry Argument

An alleged asymmetry

All normal beliefs (when we are trying to find the truth) are based upon what seems to us to be the case. I treat all appearances the same, prima facie: appearances of all kinds provide justification for their contents, in the absence of grounds for doubt.

But indirect realists posit an asymmetry: when you have perceptual appearances, you don’t acquire immediate justification for believing their contents; instead, you only acquire immediate justification for believing that the mental state exists. Then you have to construct an Inference to the Best Explanation (IBE) to justify the claim that perception is generally reliable. That IBE will itself rely on introspection (to identify the mental states to be explained), intuition (to identify the criteria of good explanations and the cogent forms of reasoning), and memory (to remember the results of previous steps in one’s reasoning).

The IR’ist treats those other faculties (introspection, memory, intuition) as sources of justification. It can’t be that you have to prove their reliability, or else you’d have an infinite regress. So you’re allowed to just start out trusting them.

But then why aren’t you allowed, similarly, to just start out trusting perception? The IR’ist needs an answer to that.

Vulnerability to error

Maybe the asymmetry is that perception is vulnerable to error, while those other kinds of cognition are not.

But of course that’s false. People are sometimes wrong about their own beliefs and desires. Intuitions are sometimes wrong. And memories are often wrong.

Acquaintance

Another answer would be that in introspection and intuition, we are acquainted with (or directly aware of) the objects, whereas we are not acquainted with physical objects.

But why deny that we are (acquainted with/directly aware of) objects that we perceive? Here is an argument from the epistemologist Richard Fumerton:

If you have a perfectly realistic hallucination of a cat, you have the same justification for believing there is a cat as you do when you veridically perceive a cat.

In the case of the hallucination, your justification for believing there is a cat does not derive from direct awareness of a cat (since you’re not in fact aware of one).

Therefore, in the case of veridical perception, your justification also does not derive from direct awareness of a cat.

My reply: (3) is correct but compatible with direct realism. In the normal perception case (but not the hallucination case) you are in fact directly aware of a cat, but that isn’t the explanation of why your belief is justified. The reason your belief is justified is, in both cases, that it appears to you that there is a cat.

Btw, notice that a parallel argument could be given about intuitions: a mistaken intuition gives you the same kind of justification for belief (in the absence of grounds for doubt) as a correct intuition. But a mistaken intuition doesn’t give you justification by giving you acquaintance with a fact that makes it true. So the correct intuition also does not provide justification by giving you acquaintance, etc.

Again, the correct account is that both the correct and the incorrect intuition provide justification in virtue of being appearances.

5. Conclusion

There are two big problems with epistemological indirect realism:

(a) It can’t explain how ordinary people have knowledge of the physical world, given that ordinary people do not base their beliefs on anything like the reasoning that indirect realists say would be necessary to justify such beliefs.

(b) It requires an arbitrary asymmetry between perception and other faculties, wherein we may start out with a default attitude of trust in introspection, memory, and reason, yet we must start out distrusting perception.

The best general theory of justification is phenomenal conservatism, which holds: it is rational to assume that things are the way they seem, unless and until one has specific reasons for doubting that. This supports direct realism: Perceptual experiences are a type of appearance that represent things about the external world. In the absence of grounds for doubt, it is rational to accept various propositions about the external world simply because these things perceptually appear to us to be the case.