1. Debunking Arguments

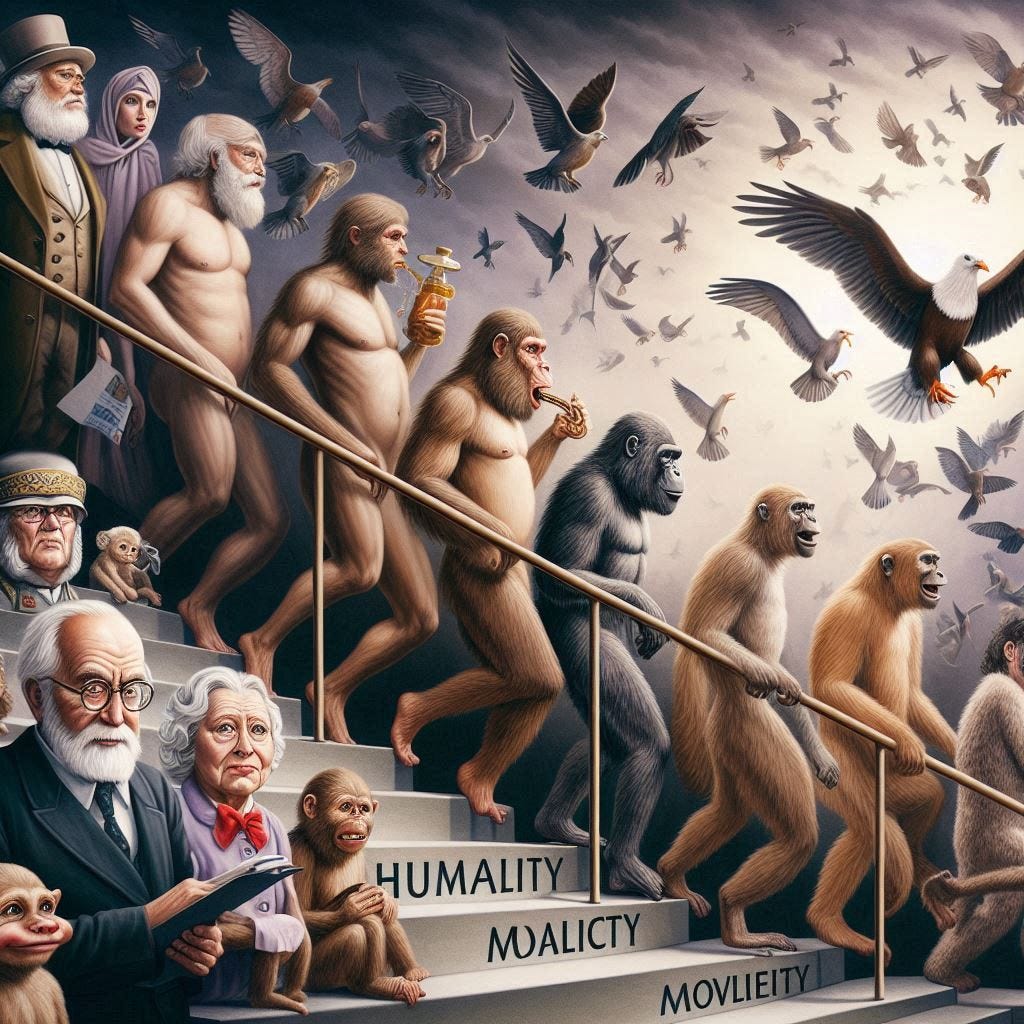

In ethics, “evolutionary debunking arguments” claim that we should not trust our moral beliefs to reflect the moral facts (if such exist), because our capacity for moral thinking evolved by natural selection, and evolution would not care about the moral facts. It would just give us the moral beliefs that most promote our survival and reproduction, and it would be a lucky coincidence if the moral beliefs that promoted reproductive fitness just happened to be the objectively correct beliefs.

From there, debunkers sometimes want you to conclude that there are no moral facts, or that morality is subjective, or that we don’t know the moral truth.

I don’t buy any debunking arguments. But here I’m going to try to work out, anyway, what the strongest debunking argument would be.

Common Objection:

All our cognitive faculties are products of evolution. E.g., our eyes evolved, along with our ears, our faculty of memory, our faculty of reasoning, etc. But no one says this means we can’t trust our eyes, ears, memory, reasoning, etc. So why would you say that about our moral reasoning capacity?

Standard debunker’s reply:

Moral cognition is crucially different from descriptive (non-moral) cognition. For most descriptive matters, whether a belief promotes fitness depends on whether it is true. E.g., whether it’s adaptive to believe a bear is approaching depends on whether a bear is in fact approaching.

But moral beliefs are different: their contribution to our fitness is completely independent of whether there are any moral facts corresponding to them. E.g., the belief that you are obligated to care for your children promotes fitness whether or not such an obligation really exists.

So evolution would “want” our descriptive beliefs to be true but it would “not care” whether our moral beliefs were true.

2. Some Problems

I’ve written about some problems with debunking arguments before. But here are some different problems:

The adaptationist theory of morality does a poor job of predicting the content of our moral beliefs. E.g., if the evolutionary theory were true,

Shouldn’t most people believe something close to ethical egoism? But hardly anyone believes egoism; indeed, many think egoism doesn’t even count as a moral theory.

Shouldn’t most people think that the main duty in life is reproduction? Yet I know of no one who thinks that.

Most people have extremely low moral motivation. Ex.:

We know from the Milgram experiment that 2/3 of people are willing to murder someone in order to avoid the social discomfort of defying an authority figure.

Something like 97% of people are happy to cause enormous amounts of suffering and death to members of other species, just to get a little extra pleasure for themselves during meal times. Btw, almost all students can be convinced that this is morally wrong, but almost everyone just says that they plan to continue to be immoral.

If morality is an adaptation, wouldn’t we expect evolution to have given us a stronger motivation to listen to it? Btw, Michael Ruse suggests that the (alleged) illusion of objective moral facts evolved to enhance the motivational force of moral beliefs: because we feel like they are objective facts, we feel like we have no choice but to obey morality. But that’s just not true: people happily defy morality all the time (as long as they won’t get punished or suffer social disapproval).

3. The Alternative Debunking Theory

The smart debunker can answer these objections. The key is that, while standard attempts to explain morality assume that moral beliefs mainly function to guide your own behavior, the alternative debunking theory assumes that moral beliefs mainly function to guide how you try to make other people behave. In brief, moral obligations are demands you impose on others.

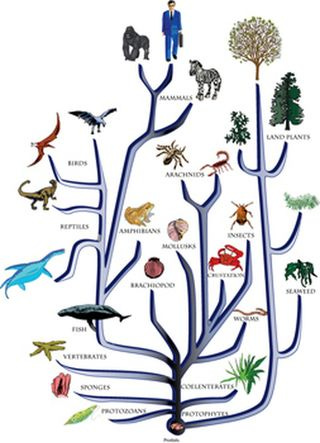

Let’s back up. Most species are non-social. These non-social species have evolved various drives that tended (in their evolutionary past) to make them behave in roughly reproduction-maximizing ways. This will generally involve what looks to us like “selfish” behavior. (I’m not sure if it literally counts as “selfish” for these animals.)

Then social life evolved. But if a social animal behaves “selfishly” in the group (especially among humans, who have many opportunities for such), this harms other members of the group. So evolution developed adaptations that would help individuals to stop others in their group from behaving overly selfishly. We developed certain negative emotions—basically, we feel blame or outrage when we see people behaving in ways that, if tolerated, would undermine social cooperation. These emotions make us want to punish those others. This, in turn, deters people from behaving badly (i.e., anti-socially) in the future.

Then, so the debunking theory goes, when we became smart enough to think abstractly, we started to confusedly attribute a special property, “wrongness”, to the actions that gave us these emotions. We tried to systematically describe these types of actions—and that was the origin of “moral principles” and “moral theories”.

Q: How does it benefit you personally to try to enforce morality?

A: We benefit by punishing moral violations that were committed against ourselves, since this deters future violations. Also, powerful people might benefit from enforcing morality by having their social group be more successful, resulting in their having more power and being better able to defend against rival groups. Maybe less-powerful people also benefit by enforcing morality because they thereby gain the favor of the powerful.

Q: How does this theory solve the problems of sec. 2?

A:

The reason why egoism is not a popular moral theory is that we don’t benefit (in terms of reproductive fitness) from other people behaving egoistically.

Similarly for the view that reproduction is obligatory.

The theory doesn’t require that people have strong intrinsic motivation to be moral, but only that they are motivated to punish others for being immoral. This, I think, fits with our observations of human nature. It really does seem (to me, at least) that most people care a lot more about other people’s alleged moral transgressions than they do about their own. This is the explanation for hypocrisy.

Q: What about the moral beliefs that the standard approach really does seem to explain?

E.g., the standard approach explains why most people think it’s obligatory to care for your own children (and that this is much more important than caring for other people’s children). How would the alternative debunking theory explain this?

One possibility is that we feel it’s obligatory to care for your own children because failure to do so has traditionally resulted in imposing burdens on the rest of society (because then other people would step in to care for them). (This invites the question of why the other people would do that. Maybe this is just the nature of social life.)

Or maybe this isn’t one of the moral beliefs produced by evolution. Perhaps, after evolution created our moral sense, that sense was partly coopted by cultures, which train people to view additional things as “wrong” that evolution didn’t initially select. And maybe “it’s obligatory to care for your kids” is one of those things inculcated into us by our culture.

Or maybe our concept of “wrong” is really a sort of amalgamation of different things that we have distinct negative emotions toward. So maybe one kind of “wrongness” is the stuff that makes us mad when other people do it, and another kind is the stuff that makes us feel bad when we ourselves do it. We just confused those different categories and gave them a single label.

Q: What about more advanced, liberal beliefs?

For example, what explains the belief among smart, non-self-deceived people that buying animal products from factory farms is wrong?

A: Maybe this is a byproduct, a consequence that evolution didn’t intend, of the previously-mentioned human tendencies, together with our general reasoning capacities. Once we confusedly decided that there was a property of “wrongness”, some small fraction of us started trying to work out what properties it has. These smart people then found it implausible, if objective wrongness exists, that it would conveniently happen that it’s only wrong to harm humans. They couldn’t figure out a reason why the objective moral facts would be tied to the interests of our species in particular. So they inferred that wrongness must also attach to harming conscious beings of other species.

4. Is it a Good Theory?

So that’s the most plausible sort of debunking theory I can think of. It appeals to evolution to explain the origin of moral emotions, which in turn are the ultimate source of moral beliefs. But it doesn’t claim that evolution directly selected moral beliefs, nor does it claim that all aspects of morality can be explained as adaptations, since, once we had moral beliefs, cultures could influence them.

One weakness of such a theory is that it requires complications that make it overly flexible. You have to explain such beliefs as

a) It’s wrong to harm others for your own benefit.

b) It’s obligatory to care for your children.

c) But it’s not obligatory to have children in the first place.

d) We should take account of the interests of other species, not just humans.

As I explained it above, the theory lets you explain all of these, but that’s because it probably enables you to “explain” just about any moral belief content (or at least an extremely wide range). The theory now claims that some moral beliefs arose because it’s beneficial to make other people follow them, while others arose because it’s beneficial for you yourself to follow them. Hence, roughly speaking, you can explain both selfish norms and unselfish norms.

Given this extreme flexibility, the theory is close to unfalsifiable, and close to not really making any predictions. The fact that such a theory could be used to explain our moral beliefs in a way that doesn’t suppose their truth isn’t really a powerful undercutting defeater for those beliefs. One can almost always come up with that kind of theory to explain any kind of belief.

To take a more extreme case, the “Simulation Hypothesis” can explain our beliefs about the external world without supposing the truth of those beliefs. Does that undermine our justification for those beliefs? Not really, or not to any significant degree. One reason is that the Simulation Hypothesis is too flexible: it’s compatible with essentially any sequence of experiences that you could have. Which means it doesn’t really predict anything. (Similar to the BIV theory.) Which means there’s no evidence for it.

Likewise, there’s little or no evidence for the debunking theory as a whole. Then, when you add in beliefs like (d) (that we have to take account of the interests of other species), you get uncomfortably close to actually relying on some of the very ethical intuitions that you’re trying to undercut. I.e., when you’re saying that rational reflection makes it plausible that (d) would be true if there were to be objective moral values, that’s steering pretty close to the intuitionists’ idea that rational reflection tells us what we should do. This move is almost tailor made to accommodate any moral beliefs that a moral realist could accommodate.

And why is this sort of extreme flexibility a problem? Well,

(a) I assume that the debunker has to not merely cite a possible way that we could be deceived; they have to say that we have good reason to think that way is actual. (This is what’s supposed to differentiate it from the sort of skeptical scenarios that you can make up for any belief.)

(b) But in general, the justification for a theory depends on the theory’s making specific predictions (predictions that would be unlikely to be true if the theory weren’t correct), and those predictions coming true. If your theory makes no predictions, or only predicts things that you would also pretty much expect on the main alternative theories, then there’s little or no reason to believe the theory.

. . .

I haven’t tried to set up a straw man here. Section 3 is really my best attempt to give a debunking explanation of morality. I just don’t see any way of doing that without resorting to the sort of postulates that would enable you to accommodate just about anything. Anyone have any better ideas?

I'm in agreement that global debunking arguments aren't particularly strong, but they don't have to be in order to debunk moral realism, IMO. They just have to be stronger than the arguments for moral realism, and I don't think those arguments are all that strong.

So, for example, what is the moral realists' theory of how we came to have our moral views, when they are accurate to the objective facts? It's something like: We developed this ability to reason, the ability to reason somehow gets us moral intuitions (perhaps in the same way it gets us mathematical intuitions). We weigh these intuitions against each other (because they often seem to conflict) in order to figure out the moral facts.

My portrayal of the theory above is meant to highlight the two big problems for it. First, how does the ability to reason get us accurate moral intuitions? I get why it gets us accurate mathematical intuitions: we can see at a glance that the shortest line between two points is a straight line when we just consider the proposition on its own because our minds are fast at reasoning about particular things and the proposition makes sense by itself, which is why we can double check our immediate reasoning afterwards.

Yet, moral intuitions aren't like that. For all the fundamental moral intuitions, you can't just double check whether they are true by reasoning about them. Instead, they just seem true, irrespective of reasoning. They seem more like perceptions of the world (e.g. my pillow is navy blue) in that regard. I can't reason my way to "my pillow is blue", I can just look and see that it is blue. Yet, how is it possible to just look and see that "stealing is wrong"? There's no apparent mechanism even when we try looking for one (there is no moral equivalent of photons or photoreceptor cells). This should undermine our trust in moral intuitions to a large extent.

Second, if intuitions are just a result of reasoning, why do they conflict so often? Why do we have to weigh them against one another? This doesn't seem to be true of mathematical intuitions (except in the sort of fringe cases mathematicians debate about, maybe). There's a strong case, even if you are a moral intuitionist and moral realist, that most of your moral intuitions are mistaken (i.e. that moral intuitions are wrong more often than they are right). It seems like our moral intuitions are not mostly a product of reasoning (even of the immediate sort of reasoning I discussed with mathematical intuitions above), but must be distorted by other factors away from the truth.

Presumably, the moral realist will say this is because of particular debunking factors: our selfishness debunks this intuition, our shortsightedness debunks this one, and so on. Yet, this is just to admit two things. First, it admits that many (if not most, as I suggested above) of our moral intuitions are the product of biases, not reasoning. Yet, if so, then there's not as large a step from "many/most of our moral intuitions are debunked" to "all of our moral intuitions are debunked" as there would be if the vast majority of our intuitions were trustworthy (i.e. you need much less justification to make the jump now). Second, by admitting that so many of our intuitions are not a product of reasoning but instead a result of debunking factors, it gives you a strong inductive reason to think they all are debunked (and so gives you some justification for making the jump).

These two problems alone don't defeat the moral realists' theory of how moral intuitions can (sometimes) come to reflect objective moral facts (i.e. they don't actually justify jumping to the conclusion that all moral intuitions are debunked), but they make the moral realists' theory pretty weak and thus make it much easier for even a relatively-weak alternative (e.g. the universal debunking argument in this post) to come along and defeat it. The alternative just has to be slightly better than the realist option.

Disclaimer: I know that moral realists present other important arguments for their views, but I do think that the ones based on moral intuitions are the strongest (e.g. the Moorean argument), and so the problems above will (I think) be pretty big problems for all of the best arguments for moral realism. That's because they provide reasons to think our moral intuitions specifically are untrustworthy.

I think this is generally a straw man attack on adaptationist theories of morality. For actual adaptationist theories of morality, I’d recommend checking out Oliver Curry’s work on morality as cooperation (he might actually agree with you on moral realism), Baumard’s work on mutualistic morality, DeScioli and Kurzban’s work on dynamic coordination theory, Pat Barclay’s work on social markets (which explains our judginess and virtue signaling), and my own paper “the evolution of social paradoxes.” Also, even if you don’t end up buying any of these approaches (or any combination of them), what’s your alternative? That we magically intuit correct moral truths just because? At least adaptationists are trying to come up with a good theory. You don’t even have a theory. Obviously morality had to come from evolution in some way, whether biological evolution or cultural evolution or some combination. And these evolutionary processes aren’t designed to track moral truth. So what’s your explanations for how some people’s moral intuitions (I’m assuming you mean “your own”) happened to converge on the moral truth? Where did this moral truth faculty come from, if not from evolution? From god? I’m actually not even a moral antirealist, but I do think you’re being overly dismissive of their arguments.