Positivism

What is positivism? Basically, positivism (or “logical positivism”) = empiricism + verificationism.

Empiricism: The thesis that there is no synthetic, a priori knowledge.

Verificationism (or “the verification criterion of meaning”): Roughly, the view that the meaning of a sentence is given by its verification conditions. To understand a sentence’s meaning is to know under what conditions it counts as being verified or refuted. If a sentence cannot be tested, then it is meaningless.

This was a surprisingly popular view in the early to mid 20th century, before it lost favor among philosophers due to being obviously false. However, not everyone has gotten the memo. Philosophers have generally given it up, but scientists are still often influenced by (il)logical positivism, and some modern scientific theories are largely based on positivistic philosophy.

I talked about empiricism before (https://fakenous.net/?p=2638), so here let’s focus on the error of verificationism.

[Clarification: by “meaningless”, they don’t mean “pointless”. They’re not saying that it’s idle to talk about untestable theories. They literally mean that an untestable sentence does not even assert anything. It has no propositional content. It’s meaningless in the way that “Blug trish ithong” is meaningless.]

[Qualifications: After deciding to embrace the rough idea above, positivists modified the view to make it less easily refutable. E.g., they decided that a sentence did not have to be capable of being decisively verified or refuted; it was enough that there could be some evidence for or against it. Also, they allowed that some of these “meaningless” sentences had a legitimate use in our language, e.g., perhaps to express our feelings about something (“emotive meaning”), rather than to assert any proposition (“cognitive meaning”). The verification criterion only applies to cognitive meaning, not emotive meaning.]

What Is Confused About this Theory?

The motivation for positivism

First, what was the motivation for the verification criterion in the first place? In some writings, it’s pretty clear (because the positivists more or less come out and say it) that verificationism was devised as a rationalization for dismissing some wide swaths of philosophy that they (understandably) didn’t want to have to engage with, particularly Continental philosophy. Think of Heidegger, Foucault, Derrida. It’s plausible on its face that those people’s sentences are either meaningless or very low in meaning. So let’s come up with a general thesis that lets us rule out pretty much everything those people say as "meaningless" right off the bat.

(Note: it’s interesting to read Carnap’s famous article “The Elimination of Metaphysics Through Logical Analysis of Language”, wherein he memorably explains why a certain passage from Heidegger, containing the phrase, “The Nothing nothings”, is meaningless.)

The Core Confusion

Still, there would have to be at least some prima facie plausibility to the verification criterion, at least for some people, in order for it to be a suitable cudgel against Continental philosophers. Why would anyone find the verification criterion plausible? In general, the positivist writers just dogmatically asserted it, then started deducing consequences from it.

But I’ve figured out a plausible motivation. The theory is motivated by a confusion between the concept of knowledge and the concept of truth. I take it that I don’t have to explain why those are different, right? It’s one thing for a proposition to in fact be true; it’s quite another for us to know that it is. But suppose you confuse those things anyway. Then you get something like this thinking:

Meaning is truth conditions. I.e., to understand the meaning of a sentence is to understand under what conditions the sentence would be true or false.

Truth = knowledge.

Therefore, meaning is verification conditions. I.e., to understand the meaning of a sentence is to understand under what conditions the sentence would be known to be true or known to be false.

Premise 1 is a plausible account of meaning. Premise 2 is an egregious confusion. If you start with the plausible account, then commit the egregious confusion, then you wind up with verificationism. Of course, no positivist would explicitly say the above argument. The thing about confusions is that you can’t make them fully explicit, or else it’s obvious that you’ve gone wrong. So what I’m suggesting is that (1) just seems plausible, then the positivists confused truth with knowledge, and then (3) seemed plausible to them.

This is, by the way, a variant of the Fallacy of Subjectivism (https://fakenous.net/?p=2697). Confusing the truth of a statement with our knowledge thereof is a way of confusing reality with our representations.

Of course, once we see the mistake, we have an argument against verificationism:

Meaning is truth conditions.

Truth does not = knowledge.

Therefore, meaning is not verification conditions.

Meaning Is Compositional

Another problem is that meaning is compositional. I.e., if you have words that are meaningful, and you combine them in ways that make sense, you get a meaningful sentence. The sentence is rendered meaningful by the meanings of the individual words and the way they’re combined – which does not require there to be verification conditions for the whole sentence.

Example: I can say there is an undetectable turtle in my house. This sentence can’t be tested. However, each word in it is meaningful (and in case you don’t like “undetectable”, note that “detectable” is meaningful and “not” is meaningful), and the words are combined in a way that makes sense.

If you allow compositional meanings, there’s no way of guaranteeing that someone can’t form untestable sentences.

Counter-examples

The positivists were constantly adducing decisive counterexamples to their own theory. They were really good at that. Only they didn’t admit that this was what they were doing; instead, they’d just deduce absurd consequences of their theory and declare those consequences to be proven true by the theory.

First example

Positivists traditionally declared religious statements like “God exists” and “There is an afterlife” to be meaningless, since they (allegedly) could not be tested. These are just obvious counterexamples to verificationism. These are not borderline cases of “meaningful” sentences; they are perfectly clear (to anyone who isn’t a dogmatic positivist ideologue) examples of meaningful sentences.

Second example

Positivists also claimed that ethical statements like “Abortion is wrong” were meaningless since, again, they can’t be empirically tested. Again, this is just a perfectly clear counterexample to their theory.

[A.J. Ayer claimed that “abortion is wrong” served only to express emotions, rather than to assert a proposition. This view is refuted by the Frege-Geach problem – roughly, the fact that you can stick “abortion is wrong” into any linguistic context that requires a proposition-expressing phrase. E.g., “I wonder whether ____”, “Probably, ____”, “If ____, then Q”, “It’s not the case that ____”, etc.)]

Third example

Positivists claimed that certain pairs of theories that explicitly contradict each other really meant the same thing. E.g., there is the theory of relativity, which posits a non-Euclidean geometry to explain gravitational phenomena. Then there is an alternative theory which would use a perfectly Euclidean geometry but which would claim that gravitational fields cause distortions in the sizes of all objects that encounter them (including light rays). Reichenbach and Carnap both claimed that these are really the same theory, because they make the same empirical predictions.

(To understand why they make the same predictions, see Reichenbach’s Philosophy of Space and Time.)

Again, this is just a clear counter-example to verificationism, since those obviously on their face are not the same theory. (Btw, there are similar examples arising from different interpretations of quantum mechanics. And many more counterexamples could be given.)

To rephrase the problem: Each of these consequences of logical positivism seems obviously false on its face. I.e., a normal person who wasn’t already committed to positivism would think they are false. So we would need a pretty good reason for thinking they are true (that “God exists” is meaningless, “Abortion is wrong” is meaningless, etc.). The positivists offer no reason, other than deducing these things from the verification criterion of meaning. But there is no reason to accept the verification criterion in the first place if it can’t account for what seem to be perfectly clear cases of meaningful sentences.

Consequences

So you see why positivism is irrational. Why is it also intellectually harmful?

One problem is that (il)logical positivism causes you to dismiss lots of interesting questions … like the entire field of ethics.

Another problem is that (il)logical positivism infected our scientific theories in the 20th century, in a way that is still with us today. The above example (example 3) illustrates this. In that example, there’s a theory that provides an alternative to general relativity that is equally well supported by the empirical evidence. Scientists generally ignore this, though, because it doesn’t make different empirical predictions; this is partly under the influence of positivism.

Another example is how physicists steadfastly reject the idea of a preferred reference frame (the absence of any such preferred frame is the key tenet of special relativity). One motivation for this is the positivistic one: If there were to be a preferred reference frame, all indications are that it is undetectable (i.e., we can’t empirically measure our absolute velocity). But then there would have to be facts that can’t be verified. But we “know” from logical positivism that there can’t be any such facts (or at least that no one could possibly talk about such).

[Note: If you’d like to see how positivism motivated the theory of relativity, see Albert Einstein’s book Relativity: The Special and the General Theory. He is totally explicit about it.]

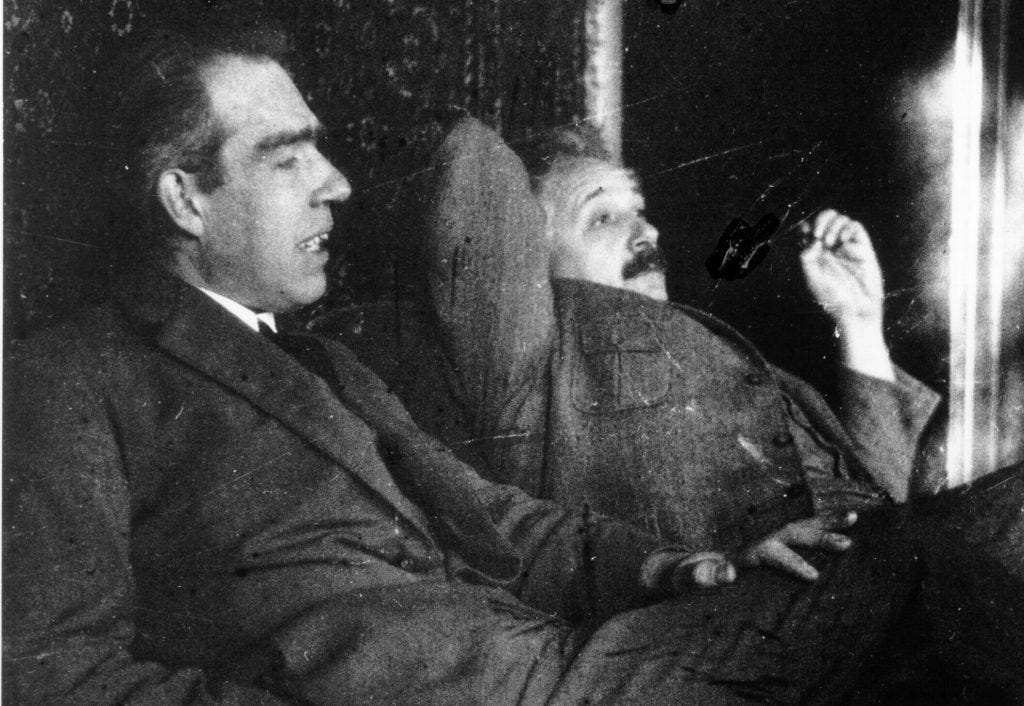

Another example concerns the interpretation of quantum mechanics. Einstein had cause to regret his earlier invocation of positivistic principles when he had his debate with Bohr about QM. Roughly speaking, Einstein thought that reality was always fully determinate (things had definite properties, even if we didn’t know what they were). Bohr, as a good positivist, argued that if some set of information cannot in principle be known (as occurs in QM), then the information doesn’t exist, i.e., reality is just indeterminate. For instance, if you can’t know the position & momentum of a particle at the same time, then in fact no particle has a position and a momentum at the same time.

Today, students are regularly taught theories that have their roots in positivist dogma. Philosophers figured out that positivism was false by the late 20th Century, but scientists had stopped listening to philosophers by that time, so we still have theories that are based on it.