The Fallacy of Rationalism

I’ve spent a fair amount of time thinking about how human thinking goes wrong. You could call this “applied epistemology”. It’s really striking how often human thinking goes wrong, and in how many ways.

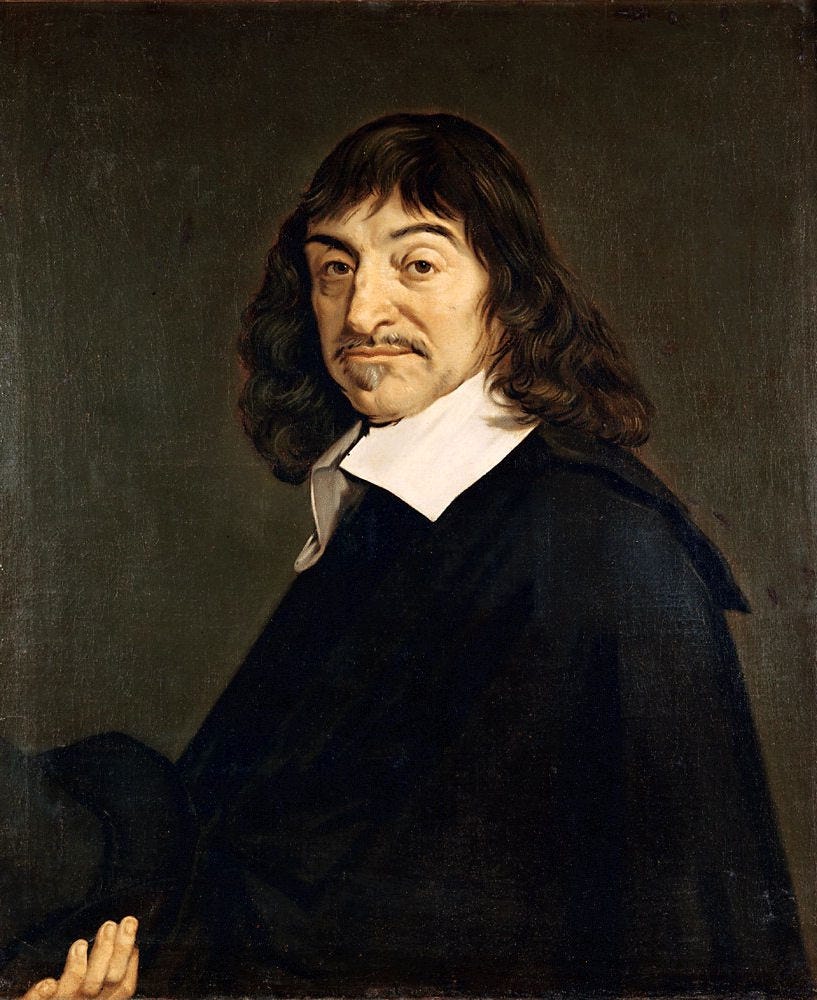

Anyway, it seems to me that there is a cluster of misguided thoughts and ways of reasoning that are generally associated with rationalist philosophers, such as Plato and Descartes, and which remain tempting for many people today. The rationalistic mindset is perennial — each new generation has people who are born with rationalistic dispositions. (I myself am a natural rationalist, but after some learning and reflection, I’ve become critical of it.)

So, how do rationalists think, and what’s wrong with it?

Rationalism

On Words & Concepts

Rationalists are tempted to identify concepts with definitions. They think that the way to understand a word or concept (or the best way, the most genuine way) is to understand the definition of that word or concept, and the inability to define X means that one “does not know what X is”.

Some rationalists place great faith in our ability to precisely define things, e.g., Spinoza. Others notice that we can’t define much, and they draw a skeptical conclusion. Thus, Socrates claims to know nothing because he can’t define “virtue”, “piety”, “knowledge”, etc. Since he can’t define these things, he must not know what they are; since he doesn’t even know what they are, he must know very little indeed.

Most rationalists probably haven’t explicitly formulated their view and wouldn’t call themselves “rationalists”. I’m including non-philosophers, including thinkers who work in other fields, as well as people in non-intellectual jobs who nevertheless have philosophical opinions. Most rationalistic thinkers are instinctive rationalists — they just have a natural tendency to think in rationalistic ways. If you’re talking to someone who insists that you have to define your terms at the start of the discussion, you’re probably talking to an instinctive rationalist.

On Principles

Rationalists think that knowledge — or at least the best, most genuine examples of knowledge — have a top-down structure. That is, the way to know things is to lay down some general, simple, abstract principles at the start, and then proceed to deduce consequences from them. Euclid’s Elements is the rationalist’s model for true knowledge. The more we can make philosophy like that, the better.

Spinoza and Leibniz are paradigmatic examples. But you see this kind of top-down approach in very many people. In some places, Ayn Rand sounds like she thinks that the axioms “Existence exists” and “A is A” entail her whole philosophical belief system. Libertarians often try to derive all their political views from one or two absolute moral principles, such as self-ownership or the non-aggression principle. It’s common for students and amateur philosophers on the internet to try to do similar rationalistic things, with various different allegedly self-evident axioms alleged to support big, controversial conclusions.

On Knowing How

The rationalistic view of how to accomplish some task would be that one first has to know how to do the task, and this knowing how would consist of knowing a set of propositions adequately describing the task. (It’s harder to find people who will actually say this though.)

This would apply to acquiring knowledge too. A rationalist would be tempted to think that, in order to know something, you must first know how to know things — that is, you must know some propositions that describe the correct belief-forming method that results in knowledge.

On Proofs

Similarly, a rationalist would typically think that if you know some proposition, then you should generally be able to verbally justify that proposition. You should be able, that is, to know how you know it, and the way that you know it should usually be by having inferred it from some other propositions that logically support it, and so you should be able to produce the series of steps that lead to that conclusion.

This is compatible, by the way, with accepting non-deductive, probabilistic reasoning, and a small number of “self-evident” truths that need not be derived — most rationalists are foundationalists, but they try to limit the foundations as much as possible.

On Skepticism

Rationalism has a connection with skepticism. That’s because the above ideas about how we understand/know/accomplish things are pretty hard to satisfy. Perhaps impossible. Thus, Descartes has to make some pretty unconvincing maneuvers to avoid skepticism. Many instinctive rationalists are unable to talk themselves into the sort of rationalizations Descartes comes up with, so they end up with ridiculously skeptical positions.

On Counter-examples

When confronted with an apparent counter-example to a principle he has enunciated, the rationalist’s instinct is to reject the example in favor of the principle.

For example, suppose you have laid down the principle that all concepts are formed by making faint copies of sensory images. Then you realize that there is no sensory image corresponding to causation, so your theory can’t account for the concept of causation. If you’re a rationalist, you would declare that obviously we don’t have a concept of causation, since that would be incompatible with the principle that you stated at the start.

Empiricism

As the above example shows, rationalistic thinking is not limited to the philosophers traditionally called “rationalists”. Empiricists often think in rationalistic ways as well. In fact, almost all empiricists are rationalistic thinkers.

Comment: “Rationalism” is sometimes defined as the view that there is synthetic, a priori knowledge, and “empiricism” as the view that there isn’t any synthetic, a priori knowledge. I am of course not using “rationalism” in that sense in this post. I’m using “rationalism” for a certain cluster of intellectual tendencies, as described above. And here I’m saying that most of the people who say “there is no synthetic, a priori knowledge” arrive at that conclusion via rationalistic (in my sense) thinking.

So Hume is an empiricist (in the sense of “person who denies that there is synthetic, a priori knowledge”) but also a rationalist (in the sense of “person who tends to think in the ways described above”). He promised in the Treatise to introduce the “experimental method” into philosophy, but then he totally doesn’t do that at all and just proceeds with the usual a priori, rationalistic style of thinking.

What’s the Mistake?

All of the major thinking tendencies described above are mistakes. Unfortunately, I can’t transmit to you all of my justification for saying that. Since rationalism is in fact false, that justification doesn’t consist in a few self-evident axioms and some deductions from them; rather, it comes from a lot of examples and some intuitive inferences that are difficult to articulate. But I’ll try to say something to give you the general idea of why I find rationalism misguided.

Concepts

“Don’t think, but look!”

–Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, 66

Don’t assume that most concepts have definitions. Look and see. How many of your concepts can you define? If you can name more than a few, you’re not thinking hard enough.

Philosophers have tried to define things pretty much since the dawn of philosophy (at least since Socrates). During that time, how many definitions have philosophers come up with that are today generally accepted as adequate?

The answer is zero. If you don’t know what I’m talking about, look at the literature on the definition of “knowledge”. That’s probably the concept that philosophers exerted the most effort to define. What you’ll see is that every definition that someone proposes is met with counterexamples by other philosophers. The definitions get increasingly convoluted and confusing, as do the counterexamples. This went on for decades, and still no definition has been generally accepted. All are open to strong counter-examples (which I believe most philosophers would agree to be successful counter-examples).

Because reality is complicated (more complicated than rationalists recognize), there are exceptions. Mathematics has lots of successful definitions. But there are very few outside of mathematics.

Principles

Usually (though not always, because the world is complicated), the way you know a general principle is by generalizing from particular cases. You don’t start from a general, abstract principle. You start from the particular cases.

Example: If you want to understand human behavior, the way is not to lay down a “self-evident” axiom like “All action is necessarily selfish” or “all intentional action is motivated by a belief and a desire”. The way is to look at many specific examples of human actions, and try to understand each in its own terms. Then see if any generalizations emerge from those examples.

Or suppose you want to know how we form concepts. The way to do this is not to lay down some general theory, such as “all concepts must be derived from sensory experience”, then try to interpret everything in terms of that. The way is to look at particular examples of concepts, see how they appear to have originated (this would require empirical evidence), then see if you can make any generalizations from there.

Btw, I didn’t arrive at this view by assuming it as obvious, nor by deducing it from a general theory; I arrived at it over a period of years, after seeing lots of rationalistic approaches to issues like this go wrong.

Justifications

Don’t assume that most knowledge comes from articulable justifications. Again, look and see.

Say you get a phone call from someone. You say hello. The other person says, “Hello”. And as soon as you hear that, you know that it’s your friend Sue.

How do you know that? Because each person has a distinctive voice, and having heard a person’s voice many times, you can recognize it. But how do you identify it? Exactly what properties of the voice pattern do you use to identify that specific person’s voice?

Hell if I know. I couldn’t give any criteria that would enable someone who hadn’t already heard the voice to identify it. But there is no question that this is a case of knowledge. If a witness in a trial testified that he knew that a particular person had left a certain voicemail message, you would have no problem accepting this, provided the witness was familiar with that person’s voice.

Nor is this an unusual, peripheral case. Human beings are constantly knowing things like that. We constantly recognize people, places, cars, animals, etc., without being able to articulate how we do it. It’s not that there are a few “self-evident axioms” from which we infer the rest of our beliefs. Most knowledge lacks an articulable justification, yet it isn’t naturally called “self-evident” or “axiomatic” either.

Skepticism

Epistemological skepticism rests on rationalistic thinking: Skeptics lay down some “axioms” about how knowledge has to work. On finding out that (almost) nothing that we call “knowledge” satisfies their principles, the skeptic concludes that we know (almost) nothing.

What’s the alternative way of thinking about “knowledge”? One alternative would be to start from particular cases. We form the concept of knowledge as a result of seeing cases that seem to us to resemble each other. We group those cases together and give them the name “knowledge”. The theorist’s job is to take those cases and figure out what they have in common. If your theory names some characteristics that none or almost none of the cases actually have, then you’ve failed.

This is similar to the issues of moral skepticism, skepticism about free will, aesthetic skepticism, etc. In formulating a theory, what you should be doing is trying to account for the cases that made us start talking about morality, freedom, and aesthetic properties to begin with.

Exceptions

Reality is annoyingly complicated, so almost every generalization has exceptions. In most areas, the way to proceed is bottom-up. But not always. There really are some self-evident axioms. E.g., I think transitivity of better-than (“if x is better than y, and y is better than z, then x is better than z”) is self-evident. When you have genuinely self-evident principles, you can use them to reject otherwise plausible judgments about cases.

The rationalist’s problem is really overperceiving self-evidence – they have something of a hair trigger for finding stuff “self-evident”. It’s simply not self-evident that all actions are selfish, or that all concepts are derived from experience, or that no action can be motivated by beliefs alone. Those things just have some vague plausibility before you think hard about all the cases.

Rationalists need to tone way down their perception of what is obvious or axiomatic. Tip: if the thing that you’re calling self-evident is rejected or ignored by most people who work in that field, then probably it isn’t really so self-evident. And another tip: if you’re clinging to a general principle in the face of alleged counterexamples, ask yourself if you would have enunciated that principle in the first place if you had thought of those examples first. If no, then give it up.