Tenure Doesn't Work

1. Why Do We Have Tenure?

Tenure is a weird idea. "Let's have a system where, after you've done good work for 6 years, your employer commits to employing you for the rest of your life!" Wow, this sounds really nice. I wonder why we don't have this for all jobs?

Duh, because then work quality (and showing up on time, and everything else you want employees to do) would dramatically decline after year 6. It also makes things much harder if management has to restructure the business due to changes in the market, etc.

Oh yeah. Okay. Then why wouldn't that happen to professors as well? Um . . . because professors are unlike all other humans in being selfless paragons of virtue whose only motive is to do their jobs well?

No, no. Maybe it does happen with professors; it's just that, in this one case, it's worth it to have a drop in quality because there is also an increase in academic freedom, and this freedom is more important than anything else in the academic world. Professors have to have complete job security in order to freely investigate controversial questions, and to follow wherever the evidence leads on these questions, regardless of who might be offended. The academic world is so fundamentally, absolutely committed to freedom of thought and freedom of expression that every major university has accepted this protection for their research professors, despite the obvious costs.

Yeah. That's it.

2. Tenure Does Not Protect Academic Freedom

At least, that's the standard story we tell. The problem is, tenure does a very poor job of protecting academic freedom. There are a number of reasons for this.

Methods other than firing

There are many methods to suppress free expression besides firing professors. There is the method of "deplatforming", in which people at universities dis-invite or try to silence speakers with controversial ideas. Journals and book publishers can also refuse to publish their work, conferences can reject their papers, and funding agencies can refuse them grants. There is the method of more general social ostracism. And the method of starting up mobs to shout people down, or setting up petitions and letters to attack people and call for them to be blacklisted. University administrators can also make life less pleasant for professors without firing them; for instance, a controversial professor could simply be barred from teaching a particular class, or covering certain controversial topics (example). Also, in some universities, a tenured professor who can't legally be fired can be temporarily suspended without pay.

Academics are not generally the most courageous of people, so the threat of the above measures is enough to fairly effectively impose ideological uniformity.

Now, if the academic world generally valued freedom of thought and expression, then some of the above methods would not be possible. But it has been some years since that was remotely the case.

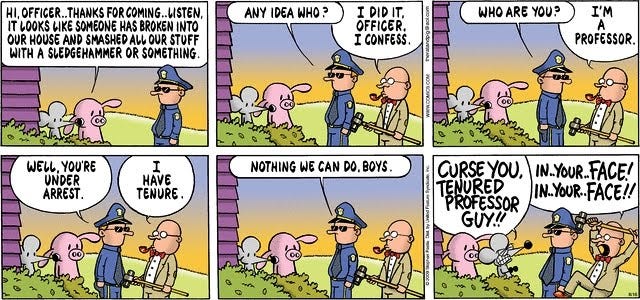

Tenured people can be fired

Of course, tenured professors can still be fired, even legally, but the conditions for this are more restricted than for untenured employees; the prof would have to have violated some fairly serious rule, or at least be accused of such. He "can't" be fired merely for expressing controversial views. That is, doing so would be against the rules.

However, really, a tenured professor can be fired for his political views, since people can in fact violate rules. It is just that they have to be prepared for the consequences if and when others see the rule-violation. In this case, if a university decides to fire a professor for his political views, then that ex-professor will have the option to file a lawsuit, at the cost of some tens of thousands of dollars, of course, which this now-unemployed professor may or may not be able to afford. The university will probably devise some pretext for firing him, and the ex-prof will have to try to prove in court that it was really his political views.

If he succeeds, he will then probably get some money from the university. He'll still be out of the university, though, and no other university will ever hire him. (Example.)

Independence is screened out

Most people are fairly consistent in their beliefs over time, and nearly all will reveal their important beliefs at some point, if observed for a period of several years. This is to say that by the end of the 6-year review period, a professor's colleagues are going to know if he has controversial political views. Therefore, if they want to discriminate, they'll do it when he comes up for tenure. The review period will simply act as a method of screening out people with unpopular views, and locking in, for life, the people who have sufficiently proved their conformity.

If, improbably enough, a person has unpopular views, or just has a general tendency to think independently, but this person does not reveal that during the 6-year review period, then the chances are that this person also will not publish controversial views after he obtains tenure either. Because people tend to be fairly consistent in their behavior. They just don't radically alter their interests, beliefs, or ways of expressing themselves after six years of conformity.

On the other hand, if the university doesn't want to discriminate, and thus will not use the tenure review process to screen out controversial people, then they also will not fire a professor for his controversial views, whether or not that professor has tenure.

So in the case where tenure is needed, it probably won't work; in the case where it would work, it isn't needed.

Empirical evidence

Of course, I am not saying that tenure has no impact whatsoever on academic freedom. It might produce some marginal increase in academic freedom. It just isn't big enough to be noticed.

One of the reasons why I think tenure doesn't protect academic freedom very well is that, after occupying the academic world for a few decades, it just does not seem to me to be a locus of free expression. American universities might be the places in the country least open to free expression. If you want to get less free, you have to go to China.

3. Tenure Protects Laziness

So tenure doesn't do very well at what it's supposed to do (protect freedom). It does, however, do a good job at what it isn't supposed to do -- protect lazy or otherwise substandard employees.

How could this be? How could it protect the people who shouldn't be protected, yet fail to protect those who should?

The reason is that tenure creates a default assumption that someone will continue in their job, one that will generally not be reexamined unless that person attracts special attention. It also makes it costly to fire an employee, whether for good cause or no.

Therefore, if a particular professor does not do anything that would attract a lot of attention to himself, or that would especially make people angry, then that professor will generally continue in his job. If all he's doing is being lazy on the job, it just isn't worth it to go to all the trouble of getting rid of this professor.

It is only the professors who defend controversial ideas who will attract enough attention, and cause enough anger, to make people start thinking of ways to make their lives unpleasant, start thinking of pretexts for firing them, etc.

Tenure creates a sort of short barrier to getting rid of a professor. The barrier is high enough to deter firing people for laziness, but not high enough to deter firing people for offensive political views.

4. The Real Function of Tenure

Tenure exists because academics want job security.

Academics are, on average, (i) intelligent, (ii) well-educated, and (iii) risk averse. Because of the first two traits, most could earn much higher salaries working in other jobs. E.g., most philosophers could have been wealthy lawyers (similar skills are used, but the hurdles for becoming a philosopher are higher). But because of the third factor, they can be attracted to work in the academic sector by job security, despite lower pay. The job security, I speculate, is more valuable to professors than flexibility is to universities, since universities really don't have a need to fire people very often.

Plus, universities don't care that much about efficiency or doing any particular job well. They would kind of prefer if you didn't become very lazy, but they don't care all that much. There is such a vast ocean of needless writings that nobody cares about, that no one will much notice if you stop adding your little trickle of verbiage into that ocean.

5. How to Protect Academic Freedom

Most academics don't believe in academic freedom anymore, if we ever did. Of course, everyone wants to be free to say what we ourselves have to say. But we don't much care about other people having the freedom to say things that other people have to say that we disagree with. Many academics are indeed actively, dogmatically, stridently opposed to academic freedom in that sense.

Of course, they wouldn't put it that way. They wouldn't say, "I hate free speech." They would say something more like, "Of course I support free speech ... for legitimate ideas! But not for objectively offensive, evil ideas that have no intellectual merit." But the latter statement is pretty much equivalent to "I hate free speech."

But suppose, counterfactually, that we cared about academic freedom. What would we do about it? Probably the most straightforward step, rather than guaranteeing lifetime job security, would be to simply make a rule that no one can be fired for controversial beliefs. This could be written into university bylaws and contracts with professors. Unlike tenure, this provision would protect instructors, adjuncts, assistant professors, and graduate students, in addition to tenured professors. We could make it even stronger: there could be a rule of "no discrimination based upon ideology," which would apply to hiring decisions, promotion decisions, and all other decisions in the university. This would be like the law that already exists prohibiting employer discrimination based on race, sex, national origin, and religion (the Civil Rights Act of 1964). It would just extend that to an additional category, and it would be a university policy rather than a federal law.

The rule could even specify what the remedy should be if an employee is fired for his beliefs. E.g., it could specify that he is entitled to be reinstated, or that he is entitled to ten years' worth of wages, or that the administrators who fired him have to be fired. These provisions, again, would be subject to enforcement by the courts. (Normally, the court decides the remedy in a lawsuit, but the parties to an agreement can specify the remedy for a breach in advance.)

Now, you might wonder about how well this would be enforced. What if administrators fired someone for controversial opinions anyway? What recourse would they have?

A: The same as in the status quo, if they fire a tenured professor. The professor can sue in court and hope to collect damages, if he can convince the jury that he was fired for his opinions. It's just that my rule would also protect free speech for non-tenured people, but it would not protect laziness.

So that's what we would do, in the hypothetical world where we cared about freedom.