Some Extreme Views in Ethics

I thought of an argument several years ago to refute rights-absolutism. Actually, part of the argument was inspired by David Friedman's objections to absolutism in The Machinery of Freedom (as I vaguely remember it, he basically says that if you're an absolutist, then you should probably hold that everything is impermissible). But the clever part of the argument I thought of myself. But then I was scooped by Jackson & Smith, in a now well-known paper: their paper giving essentially the same argument appeared while my own paper was under review. :( This made it harder, but eventually I got my argument published.

Anyway, so I'm going to tell you why absolutism is indefensible. Actually, the argument is more general than absolutism. Here are some ethical views you might hold:

Rights Absolutism: The view that rights (at least some rights?) are absolutely inviolable and can never be outweighed by any costs or benefits. If you have to choose between violating a right and letting the entire world be destroyed, you should let the world be destroyed.

*Aside: some people may regard absolutism as built into the concept of "rights". Libertarians are especially likely to be absolutists (especially baby libertarians). Now, since I know that someone is going to try to pretend that there aren't really any such crazy libertarians, I'll give you a pair of quotes from Ayn Rand:

"Since Man has inalienable individual rights, this means that the same rights are held, individually, by every man, by all men, at all times." "When we say that we hold individual rights to be inalienable, we must mean just that. Inalienable means that which we may not take away, suspend, infringe, restrict or violate—not ever, not at any time, not for any purpose whatsoever."

Deontological Absolutism: More general than rights absolutism, this is the view that there are some non-consequentialist moral concerns (maybe rights, maybe something else) that outweigh all consequentialist concerns, however large. Kant held this view. E.g., he thought that you should never lie, even to save someone's life.

Lexical Priority Views: Even more general, this is the view that there is some type of practical concern that outweighs any quantity of some other type of quantifiable concern. This is compatible with consequentialism.

Example: John Stuart Mill is usually understood as taking a lexical priority view, despite being a consequentialist. He thought there were "higher" and "lower" quality pleasures, and, apparently (?), that any amount of a higher pleasure outweighs any quantity of a lower pleasure.

The Risk Problem

So here's the problem. I'm going to phrase it in terms of rights, but you can do analogous reasoning for any lexical priority view.

Say you're considering some action that might produce some harm. Suppose it's the sort of harm such that, if you were certain that the harm would occur, then the action would be a rights violation, and hence, according to absolutists, absolutely prohibited no matter what the consequences. Now, what should you say if the action only has some non-extreme probability (neither 0 nor 1) of causing the harm? Is it still prohibited?

Example: I suppose that punishing a person for a crime they did not commit is a rights violation. So if you know that John is innocent, it would be wrong to punish him, no matter what benefits could be gained, or harms avoided, by doing so. (Anscombe says something like this, without the "rights" talk.) Okay, what about punishing a person who has some probability of being innocent?

I can think of 3 views the absolutist could take about this. All of them are extremely bad views.

The action is absolutely proscribed, as long as there is any nonzero probability of causing the harm.

The action is absolutely proscribed if the probability is 1. Otherwise, it can be justified by sufficiently large costs or benefits.

The action is absolutely proscribed if the probability is over some threshold, T, which is strictly between 0 and 1.

Problem with (1)

That view basically implies (given general facts of reality) that all actions are wrong. That's because basically every action has a nonzero probability of causing a harm of a kind such that it would be a rights violation to cause that harm with certainty.

Example: we can't punish any criminal defendants, because there is always some chance, however small, that they are innocent. So shut down the criminal justice system.

Example: Don't scratch your nose, because there is a nonzero chance that doing so will somehow set off some bizarre series of events that winds up killing someone. (If you knew that this would happen, I take it, it would be wrong to scratch. So, on view (1), it is also wrong if there is any nonzero probability of it happening.)

Problem with (2)

This view defeats the point of being a rights theorist. The probability of a harm happening is never literally 100%.

You could take this view if you want, but it wouldn't capture any of the intuitions that absolutists are trying to capture. They want their view about rights to apply to some actual actions.

Problem with (3)

This is the clever part. Say there is a threshold, T, such that if (and only if) the probability of harm is less than T, then the action can be justified by large enough costs or benefits.

There could be a pair of actions, A and B, where each of them is slightly below the threshold, and they produce large enough benefits, so both are justified. But it could also be that the combined action, A+B (the "action" of doing both A and B), is over the threshold, so A+B can not be justified by any benefits, however large.

That looks like something close to an incoherence in the theory. If you consider A+B as a single action, then it is prohibited, but if you consider A and B as two separate actions, then both are permitted. But I think that the permissibility of some behavior cannot depend on how you divide things up -- e.g., whether you count it as "one action" or "two actions".

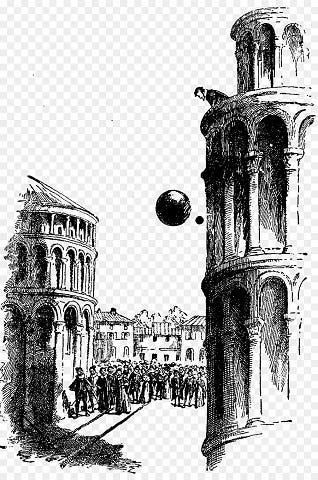

Analogy: Galileo has a great argument to show that objects should fall at the same speed regardless of their weight. Suppose you think that in general, heavier objects fall faster. If you dropped a (heavy) cannon ball and a (light) musket ball, you think the cannon ball would fall faster. Now, what if you tied the two of them together with a thin string and then dropped them? If you consider them now as one object, this one object should fall faster than the cannon ball by itself would fall. On the other hand, if you consider them as two distinct objects, then the musket ball will be trying to fall slower than the cannon ball; therefore, the musket ball will act as a drag on the cannon ball, so they will fall slower than the cannon ball by itself would fall. But it cannot be that the actual physical result depends on whether this assemblage counts as "one object" or "two objects".

Example: Think of the justice system again. Let's say that each criminal defendant is permissibly punished because each is sufficiently likely to be guilty, and the benefits are sufficiently large. But, if we run a criminal justice system in any large society, we are pretty much certain that some innocent people are going to be punished, sometimes. So the absolutist view lets you punish each of these defendants individually . . . but prohibits having the criminal justice system.

Solution

You can still be a moderate deontologist. This view holds that rights can in principle be outweighed. The existence of a "right" has the effect of raising the standards for justifying a harm. That is, it's harder to justify a rights-violating harm than an ordinary, non-rights-violating harm. E.g., you might need to have expected benefits many times greater than the harm.

This view has a coherent response to risk. The requirements for justification are simply discounted by the probability. So, suppose that, to justify killing an innocent person, it would be necessary to have (expected) benefits equal to saving 1,000 lives. (I don't know what the correct ratio should be.) Then, to justify imposing a 1% risk of killing an innocent person, it would be necessary to have expected benefits equal to saving 10 lives (= (1%)(1,000)).

Note: I think we have to say that, in order to avoid the problem where the permissibility of some behavior would depend on how we count actions.

This avoids the crazy consequences of absolutism, where, e.g., you can't scratch your nose. The probability of the nose-scratching killing someone is so small that it gets justified by the modest consequentialist reason in favor of scratching. An absolutist could not say this.