Research -- Who Needs It?

Here's the background for the title question. An enormous amount of research is being done by academics (myself included), in all manner of fields. This research is valued by the prestigious universities, which are all "research universities". They generally expect their (tenure-track) faculty to publish, and to keep publishing year after year. And there is a good deal of support of various kinds for academic research, from universities and government and private donors.

It would be of interest to have some sort of assessment of the typical value of a piece of academic research. Is most research, perhaps, intrinsically valuable? Does it produce benefits for academics? Does it produce benefits for society? If it produces benefits, are they large benefits, or small ones?

I won't comment on intrinsic value. As to the rest, I think the benefits of the vast majority of academic research are tiny at best, possibly negative, and much less than the costs.

1. The Research Status Quo

In case you're not an academic and don't know this, let me paint a brief picture of the academic research situation. (Some of this was touched on in an earlier post, http://fakenous.net/?p=768.)

a. Quantity

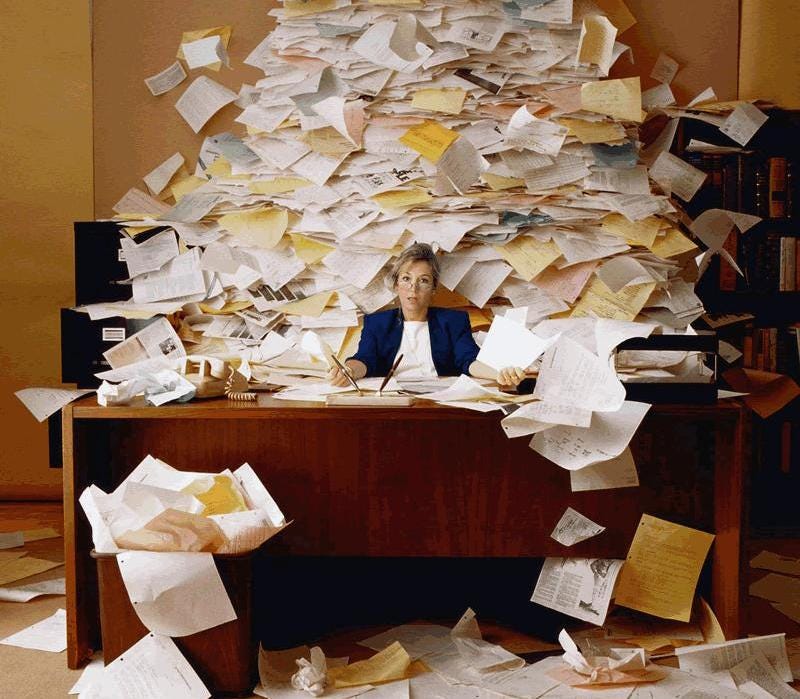

Start with the simplest feature: quantity. Now, I don't know how much total research exists, but here's what I know about my own field. I estimate there are 600 new academic philosophy articles and books written per week in the English-speaking world, or over 30,000 a year.* As this has been going on for some time, there are at least hundreds of thousands of philosophy books and articles, possibly millions.

*Basis: Many years ago, I read that the Philosopher's Index, which indexed most English-language books and articles published in philosophy, received over 14,000 new records per year. Today, a search on Philpapers.org, which again indexes most English-language philosophy papers & books (including some unpublished mss.), finds 614 records added in the past week containing the words "a", "the", "of", or "is" (restricted to professional authors only).

Philosophy, alas, is not the only field of study. I don't know exactly how many fields there are, or how philosophy compares to the others in publication quantity. But I can tell you that my university offers, by my count, a total of 79 distinct majors. I assume that all or almost all of those represent fields with their own journals, publishing their own articles. If they were all as prolific as philosophy, that would be two-and-a-half million new academic articles and books a year.

It is literally impossible to generally keep up with the literature in any academic discipline. And yet, in order to publish your own articles, you are generally expected to be familiar with the literature relevant to your topic.

The casualty of this is discussion of broad questions that bear on many other questions that we are interested in -- in other words, the most interesting sort of discussion. If you try to write about a broad question that intersects with many other issues, then you multiply the mountain of papers you have to go through to be a responsible scholar.

b. Topics

Which brings me to the second typical feature of academic research: the topics that we research. To make it possible to stay reasonably current on the relevant literature, academics have divided their fields of study into increasingly narrow sub-fields, choosing the most microscopic little questions to focus on. Even then, staying current on the literature in your own sub-sub-field is challenging.

For example, a philosopher might work on free will, in which case that might be the only thing, or almost the only thing, that that philosopher ever writes about in his entire career. And the free will philosopher's typical paper would not (as you might naively assume) address whether we have free will or not. There are too many papers and books already talking about that, so it's almost impossible to publish anything straight-out addressing that question. Rather, a typical paper would say something like: "I argue that Smith's latest response in the Northeastern Journal of Nitpicking Philosophers (2018) to Jones' objection to consequence-style arguments for the incompatibility of free will and determinism does not succeed in refuting Jones' objection. But I'm not saying Jones' objection is right, or that other responses don't refute it, and I'm not saying anything about whether free will is compatible with determinism, let alone whether we have free will."

Again, I only know my own field. But I'm sure that other academic fields are focused on similarly tiny, recherche topics that it would be hard to get anyone outside the field to care about. E.g., if someone is studying literature, they're probably writing papers on the use of arboreal imagery in the early writings of the 14th-century Ignoterran author Blabbius Obscurius.

c. Style

So the quantity of academic writings guarantees that almost all of them will be read by almost no one. The topics of these writings further guarantee that. In addition, though, even if you for some reason had a great interest in Blabbius Obscurius' early arboreal imagery, there is one more obstacle to reading most academic work: the style of the writing. Most academic writing is designed to be a creditable substitute for Benadryl, for those who need help falling asleep at night.

I take an example from Steven Pinker, who found this sentence in an academic psychology article:

"Participants read assertions whose veracity was either affirmed or denied by the subsequent presentation of an assessment word."

After some detective work, Pinker figured out what this meant: the people who participated in the study read some statements, each followed by the word "true" or "false". (https://stevenpinker.com/files/pinker/files/why_academics_stink_at_writing.pdf)

Now imagine reading a whole 25-page article written in that style. Most academic authors either don't care about readability, or don't have a clue how to produce it. Now you know why academics rarely complain of insomnia.

Here, by the way, are the actual article titles from a recent academic journal issue:

"Local Grammars and Discourse Acts in Academic Writing: A Case Study of ‘Exemplification’ in Linguistics Research Articles"

"Bringing a Social Semiotic Perspective to Secondary Teacher Education in the United States"

"Investigating the Effects of Reducing Linguistic Complexity on EAL Student Comprehension in First-year Undergraduate Assessments"

d. Support

As I say, there is a good deal of support out there for academic research. To begin with, at research universities (including all the "good" universities), the tenure-track faculty are generally given lower teaching loads -- like, half the number of classes that people have at teaching-focused schools -- to enable us to churn out more research.

Then there are things like sabbaticals (where we get to take off either half a year or a year to go do research), research fellowships (where someone provides monetary support for academics doing research for some time period, free of teaching), and grants provided by government and private donors to pay for research that has nontrivial expenses associated with it. There are things like, e.g., the NEH, the ACLS, and the Templeton Foundation.

There are also prizes given out for academic research, like the APA book prizes and various article prizes.

There are also funds available from universities and donors for things like inviting speakers from another school to come to your university, or organizing academic conferences with speakers from various universities.

And of course, prestige in the academic world is basically 100% connected to research.

2. How Good Is Research?

I had to tell you all that to give you some basis for assessing how valuable the typical piece of academic research is. Or: how much does society need more research?

a. Background Concepts from Econ

Two important ideas from economics apply here:

(1) Opportunity Costs: When we evaluate anything, what matters is usually how that thing compares to its realistic alternatives. Academic research consumes resources. So, is this research more or less valuable than the other things that we could do with those resources?

(2) Marginal Costs and Benefits: Also, when we evaluate anything, what matters for practical purposes is generally the thing's marginal cost or benefit. E.g., we have millions of academic books already, and they're here to stay. The practically relevant question is: how much value is added when another book is produced, given the supply that we already have?

When I say most academic research has little to no value, you might misunderstand this to be saying that this work lacks cognitive value, value judged by purely intellectual standards, and thus, e.g., that I would give most published articles an "F" if I were grading them. Of course that's false. Most of it is intellectually sophisticated and contains some rational reasoning contributing to some kind of knowledge. But the question is whether the addition of more such work to what we already have increases overall value to society, compared to other things we could be doing. To that, the answer is almost always no.

b. Opportunity Cost

Part of the cost of academic research is the money that goes to support it. Some of this money is charitable dollars that could of course go to support much more cost-effective measures to help the world. (See https://animalcharityevaluators.org and https://www.givewell.org for the best charitable causes.)

Here's the other main cost: academic research is absorbing the time and energies of thousands of academics. These are generally the sort of people who could be among society's most productive members. They tend to be

(i) highly intelligent; indeed, research universities house some of the highest-IQ people you'll find anywhere; and

(ii) conscientious and hardworking -- particularly those who are successful researchers at prestigious universities, which is an extremely competitive area.

Those are the main things that could make someone extremely productive and beneficial to society . . . unless that person has their prodigious abilities and energies diverted into playing insular intellectual games with other smart people.

So, to justify the amount of academic research we're doing, we would have to say that producing more of the material described in section 1 above tends to be better for society than having these people working in other areas -- whatever other professions the smartest, most hardworking people would be most likely to join if they weren't academic researchers. Does that sound likely to you?

c. Diminishing Returns

Academic publications are not like other goods, where the more of it we produce, the more of the good people can enjoy. E.g., if we produce more cars, then (for a while) more people can enjoy the benefits of a car. Not so for, e.g., philosophy books: there is no need to write additional books in order to supply additional readers of philosophy, since every person can already enjoy every philosophy book that has been written. All we have to do is copy some existing books onto new consumers' computers. As economists say, cars are a rivalrous good; books are non-rivalrous.

Furthermore, the existing books are already more than any human being could read in a million years. So no one has to write more books in order for more people to read books.

It's a little bit like if you had a thousand people working in a factory every day manufacturing blue jeans for you, when you already have a pile of 10 million pairs of blue jeans. (And you can't sell them.) The marginal value of jeans would have reached zero, if not negative.

That being said, there are still reasons why writing a new book could add some value. Perhaps none of the existing books suffices to satisfy certain consumer demands -- perhaps because some consumers have extremely specific tastes, or there are important truths that the existing books have not yet uncovered. (For example, see the books listed here: https://www.amazon.com/Michael-Huemer/e/B001H6GHNU. These obviously added enormous value to the stock of philosophy books.)

But the above reflections set a high bar. Imagine that you made a reading list containing only the best books for you to read that exist. The list contains enough books to fill up all your reading time for the rest of your life. Let's say, 500 books (I don't suppose you're going to read more than that). By stipulation, they're the best books from the standpoint of whatever you want from a book.

Now, my writing a new book benefits you only if my new book is good enough to displace one of the books on that list. So, in this example, my new book would have to be one of the 500 best books ever written (from your standpoint). There are tens of millions of books in existence, so that is a really, really tall order.

Caveat: These would be the books most suited to you as an individual reader, which is not necessarily the books that you would take to be "best" in an objective or quasi-objective sense. E.g., you might prefer to read Goodnight Moon over Principia Mathematica, even though the latter is objectively better. Readers differ a lot in what they want, so there could be many books that are among someone's top 500. So that makes it less ridiculous to think that I could now write a book that adds some value.

After thinking about the above points (even with the caveat), it is very plausible to think that most new academic books add either very little or no value at all to the existing stock of books.

Side note about science vs. humanities: It is plausible that there is a lot more room for useful research in natural science, because there really are a whole lot of extremely specific bits of scientific knowledge about tiny questions that have some practical application. The case is otherwise for knowledge whose main value is the satisfaction that readers get from learning it, which would be the case for most (putative) knowledge in the humanities. Social science is an in-between case.

d. Falsity

There are reasons why a piece of research might actually have negative value. The first reason is that, rather than expanding human knowledge, it might promote false ideas.

"Yes, but is that plausibly the case for most academic books and articles?"

Does the Pope wear a funny hat? Absofuckinglutely. Of course most philosophical articles and books are largely false. I know that because the vast majority of them conflict, in their main claims, with multiple other articles and books (usually by other philosophers). It has been said that the one thing a philosopher can be counted on to do is to disagree with other philosophers. That's how we know that philosophers are usually wrong.

Well, maybe you could be reliably right if you mainly just make negative points, pointing out errors that other philosophers have made, not advancing your own theories. Sure, and a large amount of published philosophy is like that. But that's also not a very interesting or valuable kind of philosophy, and it would be odd to try to justify producing 30,000 philosophy articles a year just to correct the errors in other philosophy articles. Unless we sometimes learn significant philosophical truths, other than truths about other philosophers' mistakes, it's hard to justify the amount of effort going into the activity.

But, again, when a philosopher advances important, substantive philosophical theses, they are usually wrong. To the extent that they persuade people, they will be worsening our understanding of the things that matter.

In case you think that this is all radically different from scientific research, which is presumably advancing our knowledge all the time, have a look at this famous article by John Ioannidis: http://robotics.cs.tamu.edu/RSS2015NegativeResults/pmed.0020124.pdf,

which explains why most published scientific research results are false. E.g., most of the time, when someone tries to replicate a published result, they can't replicate it.

e. Distraction

Here is the other reason why research may have negative value: research that is of low to medium quality makes it harder to find the research that is of the highest quality.

Imagine there is a pile of hay with some needles in it. People like to find the needles. If you add a bunch of hay to the pile, you're making things worse. Each strand of hay that isn't a needle makes it harder to find the needles.

Similarly, each mediocre article makes it harder to find the best articles. Since there are already more top-quality articles than anyone could read in their lifetime, there is no need to add anything other than top-quality articles to the pile. But of course most new articles people write are only about average, not top-quality. So there's no reason to add them to the pile.

3. The Economic Function of Research

If an alien showed up and looked at this system, they would find this all pretty strange. Why do we have hundreds of thousands of our most talented people every year spending their time churning out millions of badly-written papers, about unimportant topics, that nobody wants to read? Maybe the professors are doing it because they get paid to, or they enjoy it. But how on Earth is there money to hire all these people to do this?

Part of the answer is that the government subsidizes universities. But that really isn't the main answer. The main subsidies are student loans and grants, which explains why we have a lot of teaching but doesn't really explain why we're doing so much research. Why not cut costs by only hiring instructors and adjuncts, who get paid a fraction of what tenure-track faculty earn and do twice as much teaching? Universities must think they are getting something really important out of all this research. What is it?

The answer is prestige. The prestigious universities are the ones with the "best" faculty, which means the most well-known researchers, the ones whose work is being talked about by the other researchers. Universities care about prestige because students want to go to the most prestigious university they can. In terms of the signaling model of education, we could explain this by saying that going to a top university signals that one is extra-smart and hardworking.

So if a university hires better faculty, it can perhaps, over a long period of time, increase its prestige, which attracts more students to apply, which means it can select smarter students to come, which means that its graduates are smarter, which further increases the university's prestige and also enables the university to attract better faculty. It's a positive feedback loop.

So the goal of a piece of research is to get people to talk about that research. The literature is a bunch of intellectuals all clamoring for attention.

Prestige is different from most goods. It is a positional good, and it is zero-sum. Universities commonly measure prestige by rankings, like this one, which is very widely consulted in philosophy: https://www.philosophicalgourmet.com/overall-rankings/

The total amount of ranking-related goodness is fixed. If I help my department go up in the rankings, this is by definition at the expense of other departments.

From the standpoint of society overall, resources spent on prestige-chasing are wasted resources. If everyone spent half as much resources trying to garner prestige, the rankings would be unchanged, and the overall quantity of prestige would be about the same.

4. Will I Stop? Not a Chance.

How can I go on and on about how we don't need all this research, when I myself have already contributed more than my share to the mountains of contemporary philosophical research that hardly anyone reads? Given all I've said above, you might think that I should stop piling on.

Of course I have no intention of ceasing philosophical research. I'm going to keep turning out papers and books until I'm too feeble to type. There are a few reasons for this:

Whatever you think about the above remarks, it still is clearly the case that I individually will be appreciated and rewarded for producing more publications.

I love philosophy, and I like writing and communicating interesting ideas to others in a clear way. (E.g., this blog does not earn money or academic prestige. It's just for communicating ideas to people.)

My research is unusual in that it actually adds value to the existing body of literature, because it is better than almost all other research. In particular,

It is mainly true.

It is also reasonably well written.

It is also generally about important and interesting things.

Are my books actually among the 500 best books ever written? Well, not for all readers, of course. But for a significant portion of readers, yes, they are.

With that, I refer you to my list of books :): http://www.owl232.net/books.htm.