Privatize Law & Order

Recap from two previous posts:

The basic problem of human social life: People are selfish. How do we stop them causing enormous amounts of harm to others, to benefit themselves?

A traditional solution: Have a government to police the people.

The basic problem of government: Government officials are selfish. How do we stop them from causing enormous amounts of harm to others, to benefit themselves?

Traditional solutions to the problem of government are pretty lame. They really aren’t thought through at all well, and they don’t work very well empirically.

Here, I explain how the libertarian solution is better. I’m only going to talk about police and courts here, though; I’m not going to discuss national defense or anything else.

1. The Private Solution

The anarcho-capitalist solution to the basic social problem is similar to the government solution, except that there are multiple, competing agencies for enforcing rights, instead of just one. In other words, anarcho-capitalists want to privatize the essential functions of governments (i.e., the functions that we actually need; other functions can be eliminated).

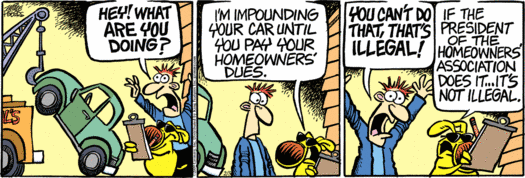

So your neighborhood could have an homeowner’s association that would hire a private security company instead of government police. Many competing security companies would operate in the same area (like security guard companies in the status quo; today, there are more private security guards in America than there are government police). In case of a dispute (including disputes about whether someone committed a crime), you would go to a private arbitration company instead of government courts. Many competing arbitrators would operate in the same area.

2. Two Differences

You might wonder whether this arrangement counts as an instance of the “government” solution — if your HOA is hiring security guards and enforcing rules, maybe it is just a small government?

That is a semantic question that doesn’t matter. But here is a substantive question that matters: Is the anarcho-capitalist solution subject to the same problems as government? Why don’t we just have the problem that, since the people running security companies and arbitration companies are selfish, they will do things that benefit themselves and harm the rest of society?

In reply, there are two important differences that explain why an-cap is better than traditional government:

2.1. Voluntariness vs. Coercion

In the anarcho-capitalist society, individuals (or private organizations) voluntarily choose to hire a security company; in our society, everyone is forced to “hire” the government, whether they want to or not.

This is important because it means that the government can give you “services” that you don’t want, that are not worth the cost, or that are even harmful on their own apart from the price. They don’t have to worry that they will lose money or go out of business, because they’ll just force you to pay for it.

Private companies, by contrast, have to offer a product that is worth more than its price, or else they lose money.

2.2. Competition vs. Monopoly

More importantly, traditional government is monopolistic — it forcibly excludes all competitors. As a result, even if you are very unhappy with it, you have no one else to turn to if you want protection from crime.

Consider the “defund the police” movement. Almost everyone’s reaction to hearing “defund the police” is along the lines of: “That’s insane. Then criminals will run rampant!” However unhappy you are with the police, you probably don’t actually want thieves, rapists, and murderers just running around doing whatever they feel like. So, even if the police are periodically killing people unnecessarily, beating up innocent people, or just doing a poor job at stopping crime, it seems like we’re forced to keep funding them. Indeed, if crime goes up, we’ll have to increase funding for the police, meaning that the police actually have an incentive to let crime get worse.

Matters are otherwise in a market with competing providers. Each provider must strive their best to satisfy customers or risk losing market share to their competitors. If your security company is doing a terrible job, you fire them and hire a different company. If the government is doing a terrible job, you give them more money so they can do better. You see the problem with this?

2.3. Other Industries

It’s amazing how little traditional political theory tries to grapple with this. Selfishness is perhaps the most basic, obvious feature of human psychology, yet most political philosophies spend less than two minutes thinking about how it is in the interests of governments to behave.

No one has difficulty seeing the analogous problem in other industries. No one would propose that the best way of ensuring that everyone’s feet are adequately protected would be to have a single shoe company forcing everyone to buy its product at whatever price it chose. You’d probably have to wait 3 years and pay $2000 for a new pair of shoes if that was our system. Everyone knows that that is how monopolies work, because human beings are selfish.

The “government” is just a monopoly on the protection-from-crime industry. That’s probably why they provide insufficient protection (most crimes are unsolved; many neighborhoods are extremely dangerous), they periodically abuse citizens, and they charge high prices. (Qualification: It’s not a complete monopoly, since you can still hire private security guards, which are much cheaper than government police and much less likely to beat you up. But the government grants itself huge special privileges.)

3. Comparison to Democratic Solutions

3.1. Separation of Powers

There is a prima facie similarity between the anarcho-capitalist idea of competing security and arbitration companies and the traditional idea of the “separation of powers” discussed previously, according to which the government is supposed to be restrained to some degree by dividing its powers among three distinct branches.

The difference is that the anarcho-capitalist idea is the version that actually makes sense. The competing security companies are actually, literally in competition: each of them wants to take customers from the others; when one company grows, the others generally shrink. By contrast, the three branches of the government are not in competition at all; they share the same “customers”, and when one grows, they all grow.

3.2. Democracy

There is also a prima facie similarity between the democratic idea of citizens controlling the government through their votes, and the capitalist idea of customers controlling companies through their purchasing decisions. Both politicians and businesspeople have to cater to the masses.

The difference, again, is that the capitalist idea is the version that actually makes sense. You actually have an incentive to pay attention and figure out which company is best, because then you can actually get that company’s product. By contrast, as discussed previously, voters have no such incentive. However diligent and rational you are in your voting decisions, you still get whatever the majority of other people vote for, so there’s no point wasting time trying to figure out who the best candidate is.

This explains why markets tend to be much more responsive to consumers than governments are. (If you haven’t noticed that, try calling up a government agency some time, tell them you’re very unhappy with their services and you want a refund. See how far you get.)

4. Competition Is a Matter of Degree

Objection: governments are actually in competition, because if your government is bad enough, you might move to another city/state/country, just like how, if you’re unhappy with your local HOA, you can move to another neighborhood. So what’s the difference between government and companies in a free market?

What this objection really points to is that competition vs. monopoly is a matter of degree. It’s not impossible to get government-like services from a provider other than your current government; it is merely difficult and costly. It can also be costly to switch providers for certain products in a free market. E.g., if you want to shop at a different supermarket, you might have to drive farther, which is slightly costly; if you want to change your HOA, you have to move, which is considerably more costly.

So here is the real problem: the real problem is having high barriers to switching providers of a good. Those barriers enable the provider to abuse you in proportion to the cost of switching. Ex.: suppose it would cost you $1 million to switch cell phone providers. In that case, the cell phone company could feel free to abuse the crap out of you, up to the point at which the abuse would be worth more than $1 million to avoid. If the cost of switching is more like $1, then they have to be a lot more careful.

So what we want is for people to have low costs to switching providers of goods. The costs of changing your HOA are pretty significant. But they are nowhere near as high as the costs of changing your government. In the latter case, you generally have to leave behind your family and friends, culture, job, etc. (assuming you could even get another country to take you in). That means that the government can abuse you a lot more than your HOA can abuse you.

I think you, David Friedman, and Bryan Caplan need to co-author an anarcho-capitalist tome that builds upon your previous works and offers a deep dive into the best arguments against it. Maybe you should consider a documentary as well.

Excellent and thanks - thanks too for continuing to publish things you've covered very well elsewhere.

One of the things that comes up in conversation about this is the inconsistency in governance. That you have all of these different orgs providing security/legal services that at some point they won't enough in common to negotiate with when two parties with two services come to (sometimes violent) disagreement. This might boil down to cultural and larger social institution similarity (e.g., in Canada you're really unlikely for things to diverge drastically that two sides cannot negotiate competently).

I'm a fan of governance competition (like with accounting certifications), and see a thread in that concern that I can't quite pull on.