Peer Disagreement @ the APA

I just got back from the Pacific APA meeting. It was in Vancouver, which is a beautiful, clean, new, sophisticated city. Due to various incompetence by American Airlines, we got to the hotel at 4 a.m., on the morning that I had a session at 9 a.m. So I went to the session tired, but I went.

I participated in a panel discussion on "Peer Disagreement". Here's the issue: you disagree with someone about some issue, perhaps a philosophical issue. You know that the other person is about equally well positioned for forming an opinion about that issue -- e.g., about as well informed, intelligent, and diligent as you. Assume (as is normal in philosophy) that discussion fails to produce agreement, although you both try to state all your reasons. How should you respond to the fact that they disagree with you? Should you just stick with your own intuitions/judgments? Should you compromise by moving your credences toward the other person's credences?

Here is roughly what I said:

Background theory:

As you all know, all justification for belief derives from appearances, that is, the states of mind whereby something seems to oneself to be the case.

Your knowledge of another subject's appearances provides a reason for belief for you, only if you have some background belief, or justification for believing, that the other person's appearances are a reliable indicator of the facts, or something like that.

Note that no such background belief is required in the case of your own appearances (this must be so, since otherwise there would be an infinite regress). So in principle, there is an epistemological asymmetry between self and other.

However, in actual fact, almost everyone has good reason to believe that other people's appearances are similarly reliable to our own appearances. E.g., I have excellent evidence that other people's vision is about as good as mine.

Now, about the problem specifically of philosophical disagreement among experts (that is, professional philosophers): it seems initially that there is something weird going on, and philosophy must be an incredibly hard discipline in which to find the truth. Because look how much disagreement there is, even among very smart, very educated experts who have spent their lives studying the issues that they are disagreeing about.

Actually, though, I think it's not so hard to understand a lot of philosophical disagreement. A lot occurs because philosophers are bad epistemic agents, in straightforward ways. Here are four ways in which we often suck as truth-seekers:

Bad motives: We feel that we have to defend a view, because it's what we've said in print in the past. So we automatically resist any reasons against it. Or we feel attracted to a theory because the theory is "interesting" and defending it will get us professional prestige. The biggest academic rewards come from giving clever arguments for views generally regarded as obviously false -- because those are the most "interesting" arguments.

Ignorance: We often ignore relevant information. Two forms of this:

We lack knowledge (esp. empirical evidence) relevant to our beliefs, when that knowledge is outside the narrow confines of our academic discipline. Example: a philosopher supports minimum wage laws, but does not know any economics, doesn't know what a "demand curve" is, etc.

We often just ignore major objections to our view, even though those objections have been published long ago. E.g., it's possible to write a book defending expressivism (formerly known as "non-cognitivism") without answering the Frege-Geach problem, which (in my opinion) refuted expressivism about 60 years ago.

Poor philosophical methodology: We often rely on incredibly vague, weak plausibility considerations, of a sort that scientists would never use in a professional paper. We often cite alleged "theoretical advantages" of a theory, while having no idea why these things are supposed to be advantages. Most common example: appealing to "simplicity" to support prima facie absurd metaphysical claims. Many, perhaps most, of our philosophical arguments are rationalizations for whatever view we were initially attracted to when we first started thinking about the subject, back when we knew hardly anything.

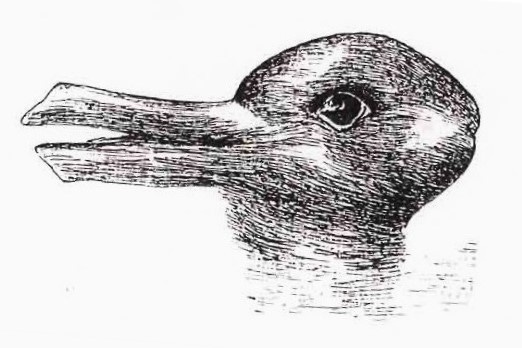

Differing intuitions. Sometimes, there are just two or more ways to "see" something. Consider how the duck-rabbit picture (made famous by Wittgenstein) can be seen as a duck or as a rabbit. Many philosophical issues are subject to that kind of gestalt "seeing" (but it's intuitive seeing, rather than literal, visual seeing), and there may be more than one gestalt possible. Usually, though, it's much harder to shift between the different ways of seeing it, and in fact most philosophers are only ever able to see it one way.

Conclusion: philosophical experts aren't very good. It's not surprising that we haven't resolved many philosophical issues.

You might think: "But I'm a philosopher too [if you are], so does that mean I should discount my own judgments too?" Answer: it depends on whether you're doing the things I just described. If you're doing most of those things, it's not that hard to tell. E.g., if you have opinions about economic matters, and you don't know any economics, you can easily know that that's the case, in which case you can stop doing that, if you care. The problem is that most of us don't care enough to ask ourselves if we are doing things like this, or to try to stop if we are.

Edit: Here is what Vancouver looked like: