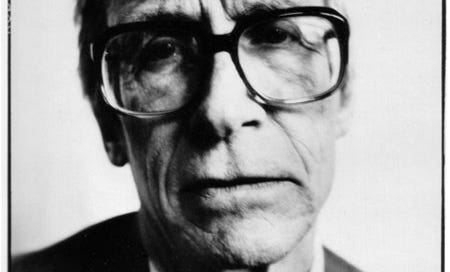

John Rawls was far and away the most influential political philosopher of the last century. For one limited measure, try searching for “John Rawls” on Google scholar. You’ll get about 16,000 hits since 2019. He was not only widely discussed but very well respected, and he acquired many followers. Even people outside philosophy have heard of him. So he clearly had some skill in a very high degree.

Whatever that skill was, though, it wasn’t skill at reasoning. Every important step in his case for his main theory is obviously fallacious and confused. At least, it’s obvious if you’re attending to the actual content of his words, rather than their sophisticated-sounding tone and the technical vocabulary. Chances are, though, if you’re a philosopher, you think I’m being horribly unfair and mean. So now I’m going to explain what I’m talking about with some examples.

I can’t detail all of Rawls’ errors. Let’s just talk about one, two-page section of his Theory of Justice: his argument for the maximin rule. (David Friedman recently reminded me in an email of this bit of Rawls’ confusion.)

Background: So, we have a hypothetical scenario, the “Original Position”, in which you’re deliberating about what fundamental political principles your society should adopt, but you don’t know what position you’re going to occupy in the society. If you’re rationally self-interested, what would you choose? Rawls says you should use the “maximin” decision rule: go for the option whose worst possible result is the least bad. Using this rule, you would then choose “the Difference Principle”: society should distribute wealth so as to maximize the wellbeing of the worst off group of people.

A different answer was given by John C. Harsanyi when he invented this hypothetical scenario (before Rawls).

Correct answer: The correct decision rule is to maximize your expected utility. Using this rule, you would choose utilitarianism: I.e., you would want your society to maximize the average welfare level of its inhabitants; this would maximize your own expected welfare level, given that you don’t know what position you’ll occupy in that society.

Note, by the way, that this disagreement is of crucial import, since one of Rawls’ central aims was to give a principled alternative to utilitarianism. If he can’t defend maximin against expected-utility-maximization, his project fails. So, why does Rawls think that maximin is better than “maximize expected utility”?

He gives several confused arguments. (He says these things in sophisticated-sounding language, though, so it sounds smart if you’re not paying too much attention.) My paraphrases of Rawls in italics (Theory of Justice, rev. ed., 134-5):

I. Ignorance of Probabilities

The people in the Original Position don’t know the probabilities of different possible conditions of society or even what all the possibilities are. I, Rawls, have stipulated this. Therefore, they cannot maximize expected utility.

Replies:

a) There is no reason why they shouldn’t know the probabilities. A philosopher can stipulate whatever he wants in his own hypothetical, but then Harsanyi could equally well just stipulate a different hypothetical in which people do know the probabilities. Since Harsanyi’s parties would be making a more informed choice (without any prejudicial information), his scenario would be more normatively relevant.

b) The parties don’t need the probabilities, since they can apply the Sure Thing Principle from decision theory. Given any coherent probability distribution over the possible outcomes, they know that they would choose utilitarianism; therefore, they can just choose utilitarianism, without needing to know the correct distribution.

Analogy to explain the Sure Thing Principle: Some person on the street tries to stop me, asking, “Do you have a minute?” Now, I know that if they’re proselytizing for Jesus, I don’t want to talk to them; if they’re campaigning for a political cause, I don’t want to talk to them; if they’re selling useless crap, I don’t want to talk to them; and if they’re begging for money, I don’t want to talk to them. (These are the only possibilities.) Since I don’t want to talk to them on any of these alternatives, I do not need to actually find out which of these things they’re doing. I can straightaway say that I don’t want to talk to them.

And to anticipate a confused reply that Rawls might make: No, you can’t avoid this by claiming that the parties don’t even know what the alternatives are. Suppose God tells me that there is actually a fifth possible purpose for which the person might be stopping me, which I haven’t thought of; however, God assures me, if I knew this fifth purpose, I still wouldn’t want to talk to the person. Then I can still conclude that I don’t want to talk to them; I don’t need to know what the fifth alternative is. It also doesn’t matter if I don’t know how many alternatives there are. (You fill in the details there.)

c) Lack of probabilities wouldn’t support maximin anyway. Maximin says you should look only at the worst possible outcome. That is equivalent to treating the worst outcome as if it had 100% probability. Not knowing the probabilities does not make it rational to act as if one particular outcome has probability 1. To see the point, notice that Rawls’ argument is neutral between maximin and maximax (“look only at the best possible outcome”), or maximed (“look only at the median possible outcome”), or the rule “Pick any option that isn’t dominated by any other.”

d) If ignorance was a problem for expected utility maximization, it would be a problem for maximin too. For Rawls says not only that the parties don’t know the probabilities of the possible outcomes; he actually says they don’t know what the possible outcomes are. (And no, this problem isn’t avoided by saying that the parties merely have “a relation” to the maximin rule. [TOJ, 135])

II. Diminishing Marginal Utility

Wealth has sharply diminishing marginal utility, above a certain minimum level. So there’s not much reason for the parties in the OP to try for greater wealth, above the amount they would get under the Difference Principle.

Replies:

a) That’s an argument for not maximizing expected wealth. It’s not an argument for not maximizing expected utility. The diminishing marginal utility of wealth is already taken into account by utilitarianism (obviously), so it can’t be an argument against utilitarianism.

b) If there is really a minimum amount of wealth that you need for a decent life, and additions above that amount give little or no improvement in your welfare, that still wouldn’t support the difference principle. Rather, it would support the principle, “maximize the number of people who are above the minimum.”

c) Rawls hasn’t supported those factual assumptions anyway. It’s plausible that there is a minimum amount of wealth needed to have a decent life, and there is also an amount above which you get no noticeable benefit from more wealth. But those two amounts are obviously not the same amount.

III. Risk

If you choose something other than the Difference Principle, it is possible that you will wind up with some extremely bad outcome that you “cannot accept”. So principles other than the Difference Principle are risky.

Replies:

a) Again, that sort of thing is already taken into account by expected utility maximization, so it can’t be an argument against expected utility maximization. Expected utility calculations take into account the chance of getting extremely bad outcomes, and they weight those possibilities according to their likelihoods. Rawls can only be proposing that such possibilities should be given extra weight – that is, out of proportion to their probability. Indeed, he’s proposing that we should act as if those outcomes are certain. But he has given no actual argument for that. The fact that some outcome is very bad does not mean we should treat it as more likely than it is, or worse than it is.

b) Compare the parallel but opposite argument: if we choose the Difference Principle, then we might forego some amazingly awesome outcome. Since you don’t want to do that, use the maximax rule instead: choose as if the best possible outcome were certain to occur.

IV. Reasonableness

The parties in the OP have to make a choice that will seem “reasonable” or “responsible” to their descendants.

Reply:

This doesn’t support the difference principle over utilitarianism, unless we assume that the difference principle is more reasonable or responsible than utilitarianism. That’s begging the question.

* * *

Again, those are just the errors in one small segment of Rawls’ master work. There are many more mistakes throughout his work.

Notice that these are not just cases where I have a differing intuition from Rawls about some controversial matter. Nor are they a matter of differing assessments of the weight of some complex body of evidence. They are cases of confusion and poor reasoning. There are pathetic dodges, such as the point where he realizes that what he just said entails that the parties in the OP actually can’t use maximin any more than they could use expected utility maximization – so he just says, “it is for this reason that I have spoken only of a relation to the maximin rule”, then immediately moves on. There are embarrassing confusions, such as the part where he apparently confuses expected utility maximization with expected wealth maximization (see II.a above). And there are the non sequiturs, like citing factors that are already included in standard expected utility calculations as reasons for the maximin rule.*

*Maybe these points were not supposed to refute expected utility maximization, but just to support maximin in general. But then the obvious error is thinking that he could support maximin without showing it to be better than the standard rational choice rule, that of expected utility maximization.

A good undergraduate would notice these mistakes. It is an embarrassment to philosophy that the world’s professional philosophers either don’t notice these sorts of mistakes, or they notice them but still think Rawls is a good reasoner anyway. When a smart person from another field, such as David Friedman, reads this kind of stuff, they wind up thinking that philosophers are dumb. Not because Rawls made these mistakes, but because the rest of the profession doesn’t notice it or doesn’t care.

If you want to argue for maximin using decision theory when you don't know the probabilities, I think the standard approach would be to appeal to Gilboa and Schmeidler (1989). A more modern version is Kochov

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1HH_zngDGUazCKEQ_bBOYOejbF15sRWNv/view

I'm not convinced by these arguments, but just mentioning in fairness.