Here, I argue that wealth redistribution violates rights. I answer recent arguments against this.*

[ *Based on: “Is Wealth Redistribution a Rights Violation?” in The Routledge Handbook of Libertarianism, ed. Jason Brennan, David Schmidtz, and Bas van der Vossen (Routledge, 2017), pp. 259-71. ]

1. The Rights Violation

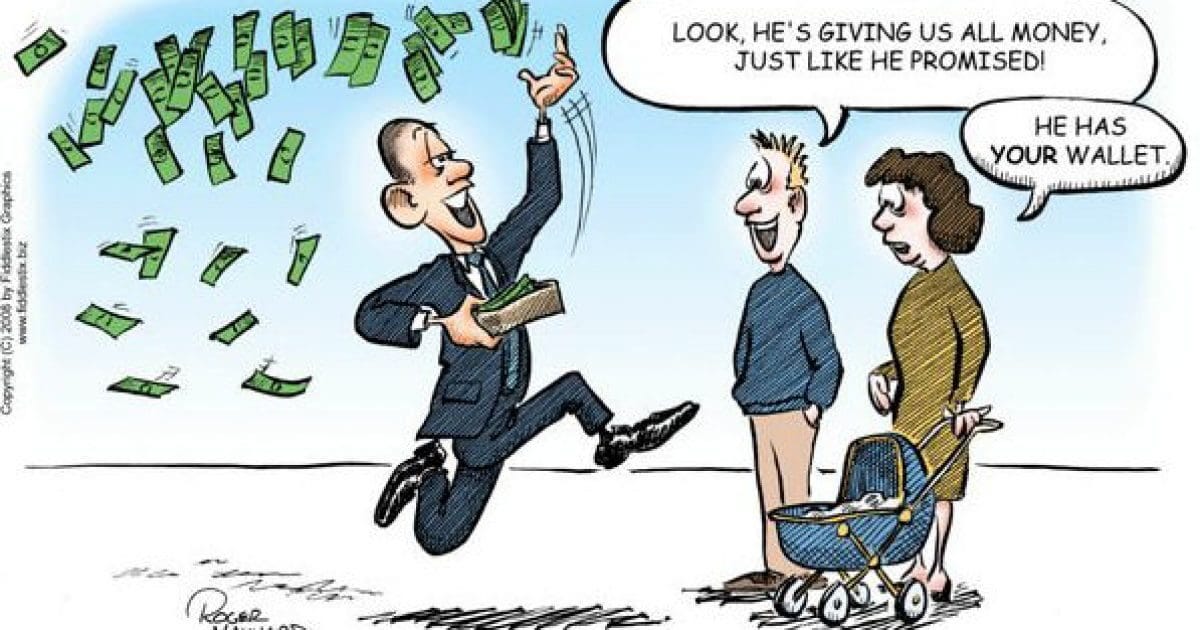

Suppose you go to one of your wealthy neighbors and demand that he hand over some of his money, under threat of kidnaping and imprisonment, so that you can give it to another neighbor. Assume that we believe in property rights in general, and that the first neighbor hasn’t done anything wrong (he didn’t steal that money, he didn’t commit a tort against the other neighbor, etc.). We would say that you are violating the first neighbor’s property rights (specifically, you are committing extortion & theft).

Yet some people think that this behavior is not a violation of anyone’s rights if done by the state. Let’s look at some reasons people give for this.

2. The Individual’s Production Depends on Others

Rich people didn’t make their money purely by their own efforts. As Obama said in a 2012 campaign speech:

“If you were successful, somebody along the line gave you some help. There was a great teacher somewhere in your life. Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive. Somebody invested in roads and bridges. If you’ve got a business – you didn’t build that. Somebody else made that happen.”

Maybe some of those other people who helped you deserve some of your money in return.

2.1. Individual contributors

Example: Jeff Bezos couldn’t make all his money on his own. He depended on his (Amazon’s) employees, and his suppliers, and the suppliers of those suppliers, and the truck drivers who bring goods to his warehouses, and the construction workers who made the roads, etc. So maybe Bezos doesn’t deserve all of his money.

Reply:

(i) All those other people already got paid for their contributions. Whatever they did, they agreed to do in exchange for a certain amount of money. Provided that they got paid the amount they agreed to, they don’t have any claim to any further benefits for their contributions.

(ii) The market tends to pay people an amount approximately equal to their marginal product, i.e., the amount that they contributed, or the difference between the productivity of the business enterprise (whatever it is that they’re contributing to) with them present and the productivity it would have without them.

Why would the market pay them this much? Because if workers are being paid less than their marginal product, that means that the business can increase its profits by hiring more workers. As they hired more workers, the productivity per worker would decline. On the other hand, if workers are being paid more than their marginal product, then the business can increase its profits by laying off some workers. So the only stable equilibrium is one where the workers are being paid equal to their marginal product.

But this is the most that anyone can reasonably expect to be paid. It’s not reasonable to expect to be included in a joint enterprise for profit, on terms such that you’re a net cost to the enterprise (such that everyone else could be made better off by expelling you).

2.2. The contributions of the state

Argument: The state provides law & order, which is essential to all business. So the state can charge money for this, and then it may spend that money on whatever it wants (just as you and I can spend our money on whatever we want, once we’ve acquired some money legitimately), including donating to the poor.

Reply: The fact that the state collects its money coercively, unlike you and me, places moral constraints on what the state can use the money for. If you think that taxation is necessary to prevent a complete breakdown of social order, that might make it okay to tax people — not because this isn’t a rights-violation, but because property rights are outweighed by the importance of preventing a breakdown of society.

However, when you justifiably violate someone’s rights to prevent some disaster from happening, you are required to do the minimal rights-violation that will attain the desired end. In this case, the state would be required to impose the minimum tax that would enable it to prevent the breakdown of social order. This would require cutting social welfare programs (as long as this wouldn’t cause a breakdown of social order).

2.3. The counterfactual test

Argument: Actually, taxation doesn’t violate your property rights, because:

An action violates your property rights only if it causes you to have less property than you would otherwise have.

If there were no taxation, then no one would have any property, because the state would collapse and then there would be a Hobbesian war of all against all.

So taxation doesn’t cause you to have less property than you would otherwise have. (From 2)

So taxation doesn’t violate your property rights. (From 1, 3)

Reply: Of course, anarchists deny (2) (see The Problem of Political Authority, part 2). But even non-anarchists should deny (1).

Example: Suppose I force you to buy yarn from me (threatening to kidnap you and lock you up if you don’t buy the yarn, etc.). This is definitely a property-rights violation, albeit a weird one. Next, suppose that you weave the yarn into colorful sweaters, which you sell for a profit. As a result of my forcing you to buy the yarn, you now have more money than you would have had if I hadn’t done it. Does this mean that I didn’t really violate your rights?

Of course not. This shows that (1) is false. You can violate somebody’s property rights in a way that causes them to wind up with more property. What makes my action a property-rights violation is that I transferred property from you without your consent -- regardless of what other effects this caused, regardless of whether it even causes you to ultimately have more property.

Similarly, even if taxation enables us to have more property, that doesn’t stop it from being a violation of property rights.

3. Reductio of the Libertarian Argument

Objection: The libertarian argument against wealth redistribution sounds like an argument against all taxation. But most libertarians accept a minimal state, which probably still requires taxation.

If taxation to fund wealth redistribution is a rights violation, then taxation to fund even a minimal state is a rights violation.

But taxation to fund a minimal state is not a rights violation.

Therefore, taxation to fund wealth redistribution is not a rights violation either.

Reply: Libertarians should reject (2). Taxation is a rights-violation, whatever the funds are used for. Minimal state libertarians may go on to argue that some rights-violations can be justified to prevent something much worse from happening. If you think that taxation is necessary to have even a minimal state, which in turn is necessary to have any social order, then taxation can be justified despite that it violates property rights.

Could taxation also be justified in a similar way, say, to prevent the poor from being unhoused?

This is harder to justify because the consequences of the poor being unhoused are much less bad than a general breakdown of social order. To gauge whether letting the poor remain unhoused is bad enough that it justifies violating property rights, imagine that I decide to collect money for my charity to house the poor. I’m not getting enough voluntary contributions, so I demand that you give me $1000. I threaten to kidnap and imprison you if you don’t pay up.

Surely this wouldn’t be permissible on my part. That shows that property rights are not outweighed by the importance of housing the poor. So the state would not be justified in taxing us to provide shelter for the poor.

4. Does the State Create Property Rights?

Argument: Property rights are created and delineated entirely by the state. Therefore, the state can simply define them such that you never had a property right to your pretax income to begin with (i.e., whatever money the state wants already belongs to the state).

Reply: It is plausible that there are some aspects of property rights that depend on convention. E.g., how long do copyrights last? That’s a matter of convention. But it is not plausible that all property rights are completely conventional. Examples:

a. Many societies have allowed slavery. But this is morally illegitimate; morally speaking, you can’t own another person, regardless of what the conventions and laws of your society say.

b. Suppose you meet a hermit on an island outside the jurisdiction of any government. The hermit has a hut and some tools that he made. It wouldn’t be okay for you to take those things, even though there is no government-made law that applies to this. This shows that there is at least some core notion of property that is natural, rather than conventional.

This is enough for the libertarian argument, because taxation violates even the most basic, core notion of property. No matter how you obtain your money, the state comes and takes a share of it. That’s a violation of property rights on even the loosest conception of property rights.

I think the analogy from a democratic state redistributing wealth to an individual unilaterally redistributing wealth is tenuous.

Say I steal from my neighbor, and my neighbor decided to lock me up in his basement in retaliation. He even finds a judge and appoints me a lawyer so I have the chance to argue my innocence, but I'm ultimately found guilty. Clearly my right to due process has been violated no matter how fair my neighbor's process was, because he lacks the legitimacy to take unilateral action against me. These same actions undertaken by a legitimate state do not constitute a rights violation.

The other disanalogy is that it's unfair to arbitrarily target specific people for a collective moral burden. Even if it would be just to take $1000 from each well-off person to give to the poor, that doesn't necessarily justify taking $1000 from a single arbitrary well-off person.

“Suppose you meet a hermit on an island outside the jurisdiction of any government. The hermit has a hut and some tools that he made. It wouldn’t be okay for you to take those things, even though there is no government-made law that applies to this. “

This raises a question about why the hermit's status would change after some government claimed his island as part of heir jurisdjurisdiction. I suppose the answer is found in your book on the problem of political authority.