Intellectual Conformity Is Adaptive

I. Better Dead than a Philosopher?

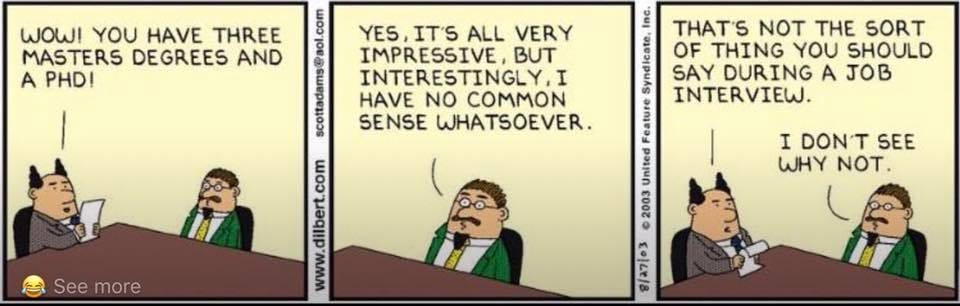

Libertarians and other people with unpopular views sometimes wonder why most human beings are so conformist. Especially intellectually. It is almost impossible to get an average human being to question received views in their society. You can give whatever amazing arguments you want, but it won't matter, because they haven't accepted the whole enterprise of adjusting beliefs in light of arguments in the first place. You can't argue a person into paying attention to arguments.

It's partly a matter of indifference to ideas. It doesn't much matter to most people what the right philosophical theory is, or the right intellectual theory of any kind, really. And it's also partly a matter of trusting the majority views, or the expert views, or the views of some other preferred person or persons. On those occasions when it becomes necessary to use some theory or other, ordinary people will assume the view of their preferred other-person source.

Ex.: try arguing with an IRS agent that taxation is unjust. If you've been around humans for a while, you know what will happen. #1: The agent will assume dogmatically that of course taxation is fine, since the government says so, etc. #2: The agent will simply not give a shit whether, in the true philosophy, taxation is really unjust.

Many intellectuals have disdainfully remarked on the presumed problem.

"Most people would rather die than think; in fact, they do so."

--Bertrand Russell

"Two percent of the people think; three percent of the people think they think; and ninety-five percent of the people would rather die than think.”

--George Bernard Shaw

Wait, it's absurd (nevermind insulting) to claim that most people "do not think". All but the most severely mentally handicapped humans employ abstract concepts, make inferences, etc. What are Russell and Shaw talking about?

Of course, Russell and Shaw are talking about a certain kind of thinking -- intellectual reflection about theoretical issues, what is often (somewhat inaccurately) termed "thinking about ideas". The sort of thinking that professional intellectuals such as Russell and Shaw are known for. Most people rarely do that.

Now, why is this?

II. The Costs of 'Thinking'

I think intellectual conformity and indifference to ideas are adaptive. I mean that in the evolutionary sense. I.e., I think that "thinking" in the Russell/Shaw sense is costly and risky. In fact, non-conformist intellectuals might be a biological accident, a rare form of human in which normally-adaptive traits reach maladaptive extremes or are combined in maladaptive ways.

Direct Social Costs

One theory about this must have occurred to many people before. It is that social conformity is adaptive because human societies tend to directly, intentionally harm people who fail to conform. For example, religious heretics and atheists might get burned, or at least be oppressed by the people with the dominant views. People with unpopular political views might be oppressed by the current political leaders. Annoying philosophers might be forced to drink hemlock.

At the very least, other humans may simply be more happy to trade and otherwise interact with you if your beliefs are similar to theirs. The best way for evolution to ensure such a match is to endow us with a bias toward social conformity.

Sharing Information

A second explanation is less nefarious. The human species has two interesting traits: it is intelligent, and it is social. Most species are neither.

The two traits are connected. What is the benefit of sociality? There is trade, division of labor, and mutual protection. But also, a major benefit is shared information.

Knowledge about the world around us is valuable, but costly to collect. (Example: Which mushrooms are edible and which are poisonous?) But once collected, it is nearly costless to transmit and receive. So there is enormous mutual benefit to be had by trading information. Only one person need take the costs of learning a given piece of information, then everyone can benefit.

How do we share knowledge? Partly by talking, of course. But we also transmit knowledge unintentionally, through our behavior. If you want to know which mushrooms are edible, you can find someone who knows, and you can ask him. Or you can watch him. This second method works even if the person doesn't want to tell you (or if, for example, he wants money in exchange for the information). When you see what he eats and what he passes over, you can infer what he believes. If you imitate what the knowledgeable person does, you gain the benefit of his knowledge, without bearing the costs he took to acquire it.

That's why humans are good imitators. It's adaptive, by and large. Don't imitate people who are failing, of course. But imitate people who are succeeding. For this adaptation to work, humans need not know why they are doing it, and they generally do not know. They just feel like imitating the high-status members of their society, and that usually works out for them.

That's the basis of culture. Now, to take full advantage of this knowledge-sharing adaptation, it helps to be intelligent, which enables you to grasp and use more information. Intelligence makes social interaction more valuable, and vice versa.

But we also get over-imitation, because natural selection is a blunt instrument, and it doesn't care about the truth of certain things (esp. abstract, theoretical issues). So the instinct for adopting the beliefs and practices that other people around you appear to have can lead to adopting false beliefs and useless practices.

Notice also that the person who undertakes the costs to acquire practical knowledge is (often) providing a public good in the economists' sense -- other people will get the benefit, if and when they figure out what this person believes. And in practical matters, he may be unable to avoid transmitting that information, since it will be revealed in his behavior, so he won't be able to charge them money for it.

So there is some reason to expect that there will be an oversupply of social conformists -- people who try to receive the benefits of others' knowledge -- and an undersupply of knowledge-producers.

Craziness

Here is the third problem with "thinking". Many thinkers in the Russell-Shaw sense are crazy. Independent, intellectual reflection leads to craziness, and intelligence is no defense against it. Conformity, however, is a defense against craziness -- at least certain kinds of craziness that would otherwise be common.

One can cite extreme cases, such as the Unabomber, who tried to start some kind of anti-technology revolution by sending mail bombs to scientists. Before his criminal career, he was a brilliant UC Berkeley mathematics professor. (Not just a regular math professor, which is already very smart, but an exceptional one.) But then he started thinking about ... industrial society and its future. Which led him to radical conclusions, which led him to start a campaign of terrorism, and landed him in prison for life. (Evolution is an asshole, so it doesn't care that he killed and maimed other people. But it was predictable that other people would respond with force, which tends to reduce one's reproductive success.)

He would have been saved from all this if he'd been more of a conformist, like normal people.

Now, you might think: "Oh, you're just picking the most extreme example of a crazy intellectual. There are hardly any people like that!"

Okay, the Unabomber is weird. But extreme beliefs among intellectuals are not unusual. Not at all. If you hear that someone is an independent-thinking, high-IQ intellectual, you should predict right away that he has some outlandish, radical beliefs, probably about politics or religion or philosophy. (By "independent-thinking", I mean that he relies on his own judgment and resists deferring to others.) You should also predict that he has some radically false beliefs. Maybe he'll turn out to be a Marxist. Or a nihilist. Or he thinks people don't exist. Or (shudder) an anarchist! We know that these sorts of intellectual opinions are highly unreliable in general, because different intellectuals come to incompatible ones.

Maybe ideal reasoners would all come to the same, perfectly correct philosophical conclusions. Evolution doesn't care about that, though, nor does it care whether it's rational to be conformist. What matters is that being an independently-minded intellectual, in the real world, is positively correlated with coming to bizarre, radical, and dangerous (to oneself as well as others) opinions. One is liable to get the idea that there is some horrific problem facing the world, and some really dangerous thing has to be done to stop it. (The fact that a horrific problem might in fact be facing the world doesn't matter to evolution, unless it is a problem that faced our ancestors in evolutionary history. But as a matter of fact, most of the time when people think there is an impending disaster, they are completely wrong.)

People who form radical, revisionary philosophical beliefs, of course, need not do anything to undermine their reproductive success. Maybe they'll just talk about how nothing matters, then go get married and have seven kids. The point is that they are at risk of doing things that undermine their reproductive success, because they form what are essentially unpredictable, extreme beliefs. One can't predict what a sufficiently smart, "critically thinking" intellectual is going to convince himself of. If these beliefs happen to line up with what evolution has carefully designed us to want to do, that is a matter of luck.

So, I speculate, evolution created an adaptation to stop the craziness: intellectual conformity. Most people get a good helping of it. Occasionally, something goes wrong in the brain and a person winds up with a disposition to think too much for himself.

By the way, being a conformist doesn't necessarily get you to the truth. Philosophy in general doesn't do so well with discovering the truth. But being a conformist will usually steer you away from the sort of crazy beliefs that would have you taking enormous costs on yourself because of some theoretical issue. Russell was mistaken: the non-thinkers do not generally die due to their refusal to think. It's more likely that the thinkers will come up with reasons to sacrifice their lives.

III. What Is Good for Society?

Intellectuals are a danger to society.* Why people constantly get things wrong when they reason abstractly is a topic for another time. But the evidence is pretty overwhelming that they do. They are then in danger of doing crazy stuff, or convincing other people to do crazy stuff.

(*Not me, though. Fortunately, I, unlike the other intellectuals, am generally right about things. But that is rare. Also, in modern times, people who work in the sciences generally advance useful knowledge. But people who think about the big philosophical, political, and religious issues generally get approximately everything wrong.)

How can society be protected from this danger? Nothing can completely protect us. But here are two ideas.

Stop teaching nonsense about thinking for yourself in critical thinking classes. We should tell students the (correct) reasons why deferring to the experts is almost always better than reasoning for yourself. That is assuming that there is an expert consensus; then you should generally go with that and reject revisionary alternatives.

This whole academic world thing is actually working out alright. It has some problems -- occasionally, academics manage to fuck up some stuff in the real world. But for the most part, society has managed to isolate the otherwise most dangerous intellectuals in a kind of posh, intellectual ghetto, where hardly anyone listens to us.

Academic jargon really helps with this. Consider the impenetrable jargon of contemporary postmodernism. Thank God it's so horribly written! If it were clear, people might listen to it.

The higher education system gives these intellectuals plenty of other weirdos to talk to in our parochial conferences and journals, which gives us the feeling that we're "getting our ideas out there" and distracts us from bothering normal people.

The crazy intellectuals get to pontificate before rooms full of young students. That would seem to be a problem. But luckily, most of the students don't pay attention, and forget whatever they "learned" fifteen minutes after the class ends.

Let's keep up the inaccessible, jargony works that no one reads. Higher education is not teaching much to students or anyone else. But at least it keeps intellectuals off the streets.

It failed in the case of the Unabomber, but it kind of almost succeeded. He had a good mathematics position -- he might have continued to do that for the rest of his life, and not bothered anyone. There must be many people who are harmlessly tucked away in academic jobs like that, researching abstract theories that don't matter but at least won't hurt anyone.

Note: of course, I have no intention of doing what I recommend for others. I plan to continue to think independently about abstract ideas and attempt to communicate radical views to others. This is okay because, again, my ideas are generally true, unlike other intellectuals.