Here, I offer praise for sitting back and doing nothing.*

[ * Based on: “In Praise of Passivity,” Studia Humana 1 (2012): 12-28. ]

1. Medieval Doctors

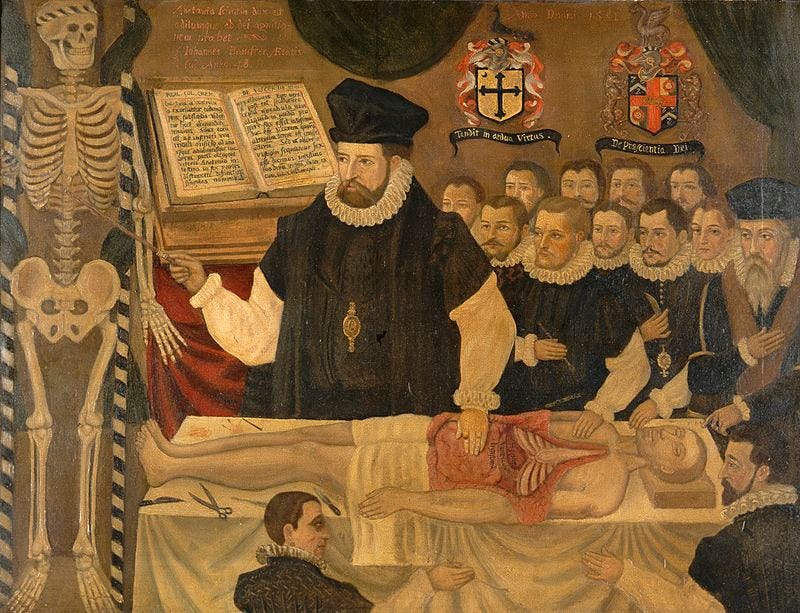

At the end of his life, George Washington developed an infection of the epiglottis of his throat, a rare and potentially life-threatening condition. He received the best medical attention available. The doctors applied “the proper remedies”, which in this case included five episodes of bloodletting that drained half of his blood. Somehow, this didn’t work. He died shortly thereafter. Needless to say, the “treatments” he received either had no effect or actually hastened the end.

This was true of many, perhaps most, medical treatments before modern times. That’s odd — these were smart people who were trying to help. How was it that they regularly made things worse?

In brief, the human body is a very complex mechanism. Fixing it requires detailed and precise knowledge of its workings and the nature of the disorder affecting it, knowledge that no one in 1799 possessed. Without that knowledge, almost all interventions are going to be harmful.

Society is kind of like that, and today’s politicians are kind of like medieval doctors. Their solutions to social problems are based on prescientific theories and emotionally driven guesses, which is why almost none of them work. In the Middle Ages, you were usually better off avoiding the doctor. Today, we’re usually better off avoiding government solutions to social problems.

2. What Do We Know?

Not enough.

2.1. Public Ignorance

Many scholars have documented the astounding ignorance of ordinary voters. E.g., most Americans don’t know their Congressman’s name, let alone his voting record. Most cannot name the form of government they live under (from the choices “direct democracy”, “republic”, “oligarchy”, and “confederacy”), nor do they know what the three branches of their government are. There are many other shocking examples of public ignorance, but the last two are particularly good because they point to the very most basic things one could possibly know about American politics. If people don’t know those things, their odds of knowing the answers to difficult, complex policy questions are about zero.

2.2. Ignoring Experts

Sometimes, experts know important things relevant to policy. But average voters and politicians frequently ignore that knowledge. E.g., almost all economists support free trade and almost all think that immigration helps the economy. But voters don’t care, and therefore politicians don’t care.

2.3. Expert Failures

Philip Tetlock did a famous study of political expertise. He asked a collection of experts to make predictions in their areas of expertise. E.g., they might be asked “will the economy of such-and-such place go into recession in the next two years?”, or “will such-and-such country have a civil war?”, or “who will win such-and-such election?”

All the questions were things that would be decisively resolved at a definite future date. Experts also provided probability estimates, indicating how sure they were of their predictions.

The result: in brief, experts did only slightly better than chance, and they were highly overconfident. E.g., when they reported being 100% certain of a prediction, that prediction would only come true 80% of the time. The experts were good at coming up with rationalizations for their failures, though.

If the experts are so bad at answering objective, factual questions that are going to be decisively resolved in the future, they’re probably even worse at answering more subjective or untestable questions, since they never have the chance to see their mistakes corrected.

2.4. Values

What about disagreements about values — say, whether freedom is more important than equality? We have “experts” (moral and political philosophers) who study these questions. But those experts can’t agree with each other. Of course, they can agree on some obvious things, like that starvation is bad. But on any issue that lay people disagree about, the experts are probably also going to be disagreeing. So we probably don’t know much about disputed value questions either.

3. Why Are We Stupid?

3.1. Rational Ignorance/Irrationality

In brief, people have no incentive to get political questions right. In a country of 300 million people, you know that you’re never going to actually have any effect on any national policy. Therefore, it doesn’t make sense for you to spend much time, or to do anything that isn’t fun, to try to figure out what the best policies are.

3.2. Who Cares About Society?

Many people appear to care: they talk about what’s good for society, they go to protests, they get upset about presumably bad policies. There are at least two motives that could explain political activism:

A desire to help society.

A desire to portray oneself (to oneself or to others) as helping society.

These lead to almost identical behaviors. But here is one difference: If you want to help society, then you need true beliefs about how to help it. If you just want to portray yourself as helping about society, you don’t need true beliefs; you just need strong beliefs about what’s good for society.

So people with motive (2) could be expected to try to maintain strong beliefs, whether true or not; people with motive (1) would scrupulously try to root out errors in their beliefs.

Which description better matches most actual political activists? I think it’s the former. So one reason why we’re bad at solving social problems is that we aren’t actually trying to solve them.

3.3. Social Theory Is Hard

Most theories that people have come up with in human history have been false. Why? To begin with, there are usually an enormous number of possible theories, all but one of which are false; however, most people don’t realize this because they can only personally think of a few. The truth is almost always something that people first considering a question didn’t think of.

Despite this, we’ve developed reliable ways of making progress in natural science. But social theory is inherently harder because the phenomena (human societies) are vastly more complicated than, say, atoms or chemicals, and we can’t perform controlled experiments on them.

4. What Should We Do?

4.1. Don’t Vote

When you vote for something, you are trying (albeit feebly) to cause that thing to be imposed on everyone in your society. That’s an immoral thing to do, unless you have pretty good knowledge about the thing you’re voting on. Since most people don’t, they shouldn’t vote.

4.2. Neglect Social Problems

There is general a presumption against government interventions. This is because government interventions involve restricting freedom, imposing harms on people who violate the law, and expending resources. Thus, if we don’t have strong reasons in favor of a government intervention, we generally shouldn’t do it.

Given our ignorance about society and how to improve it, we simply don’t have strong reasons to make most laws (including most laws that we have already made), other than the obvious ones. E.g., it’s obvious why we should have a law against murder. But for less obvious, more controversial cases (say, the government is thinking of regulating social media), the government should probably stand back and do nothing.

Just as it would have been hard to find a doctor in 1799 who would have stood by and done nothing about Washington’s illness, it would be hard to find a politician or activist who would support doing nothing to solve some social problem. But that’s nevertheless the wisest course when you don’t know what you’re doing.

4.3. Weaken Democracy

It would be better if the constitution prohibited the government from intervening in more areas — and thereby removed those areas from democratic control. In areas where the right policy is controversial, the government should usually do nothing. There should also be supermajority requirements to pass legislation — e.g., perhaps any new law should require a 70% vote of the legislature. This would allow uncontroversial laws like the murder statute, while preventing the controversial laws that are usually harmful.

4.4. Don’t Fight for What You Believe In

Most of the time, if you’re “fighting” for a cause, that means the cause is controversial, and you probably don’t actually know that the thing you’re supporting is good. If you actually want to benefit the world, a better bet is to devote your resources to uncontroversially good things, like the Against Malaria Foundation.

In politics, as in medicine, the wisest rule is, “First, do no harm.”

Very interesting post!

I find all of them persuasive, except point 4.1 about not voting. It overlooks that you’re not necessarily just picking policies to impose on someone, but you’re potentially picking someone who would impose LESS. This might not be super clear between say Biden and Trump, but many times it’s very clear, especially when one party/candidate is pushing socialism or worse.

By analogy, saying not to vote is a bit like telling one of ailing George Washington’s extended family not to help choose a doctor, because doctors are bad. But the better advice may be to help him pick a more chill doctor rather than one of the aggressive drain-half-your-blood ones (as there’s no hope of convincing him to not have one at all.)

(The feebleness of the act differs across the analogy scenarios, but I don’t think that is relevant to the point.)

Those AI images are creepy!

One thing I've been wondering about lately is whether political "passivity" -- i.e. pursuing selfish cultural pursuits instead of fighting in politics -- may, counterintuitively, have a large positive cultural impact. This is applying Adam Smith's invisible hand point about economics to culture. Perhaps selfishly enacting "freedom-oriented" culture in one's own life (e.g. going to the gun range, hunting, boating, etc.) has a much larger societal impact.