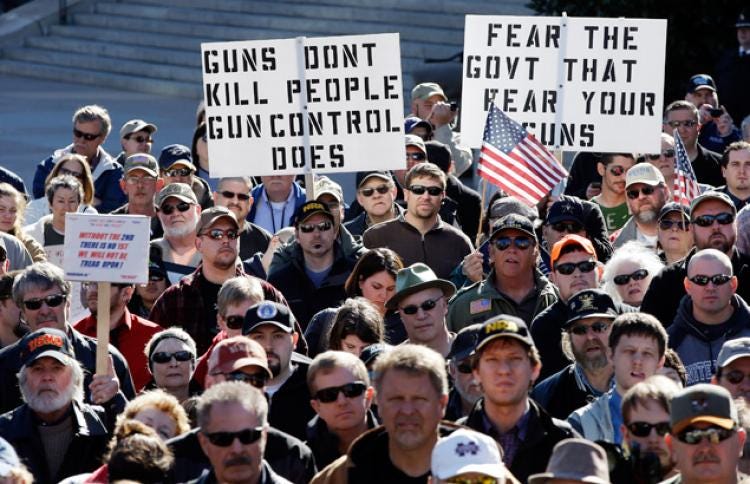

This is Part 2 of “Gun Rights & Non-Compliance”. (See previous post if you haven’t already.)

. . .

The Compliance Problem

Many confuse the question, “Would it be good for everyone to give up their guns?” with the question, “Would it be good to have a law that says everyone has to give up their guns?” These are two very different questions – for what the law prescribes is not the same as what actually happens.

Most people can appreciate this point for at least some issues. For example, the drug war. It is illegal to buy or sell marijuana, cocaine, heroin, or any of a variety of other recreational drugs. That does not mean that people do not buy and sell drugs. What it means is that they are bought and sold on the black market. It does not mean that you cannot get hold of cocaine if you want it; it means that you must buy it from criminals at high prices. It also means that the state will not enforce agreements between drug sellers and buyers, so if you feel cheated, you must enforce your rights yourself. This is why the drug trade is so prone to violence. Granted, society would be better if everyone gave up using drugs. That does not mean that society is better for having laws against using drugs.

The same was true of alcohol during the Prohibition era: massive noncompliance, expansion of organized crime, a violence-prone black market. Much the same has been true of prostitution for as long as it has been proscribed. The same will be true of guns during America’s gun prohibition era, if that era ever arrives. Some Americans will give up their weapons – but many will not. America is not England; guns play practically no role in British culture, but America, for better or worse, is another matter entirely. Many Americans love guns, which is why the country now has about 270 million guns, with an adult population of only 247 million.[1] About a third of households contain at least one gun.[2] And guns are durable; a hundred-year-old gun may still be perfectly functional. So even if we completely stop producing them right now, America’s gun stock is not going to run dry during this century. However you feel about America’s gun culture, it is a fact that has to be contended with. Pretending that people do whatever the law says has not given us a successful drug policy; it won’t give us a successful gun policy either.

The question to ask about a proposed law is never, “Would it be good if everyone followed this law?” The question is always, “Will things be better when those who are most likely to follow this law follow it, and those who can be expected to break it break it?”

There are two kinds of gun owners: criminal gun owners and noncriminal owners. Criminals (and prospective criminals) own a gun for purposes of robbing, threatening, or killing others (perhaps in addition to noncriminal purposes); noncriminal owners own a gun for purposes of self-protection, hunting, or other recreation. The ideal situation would be to disarm all the criminals, while leaving the noncriminal citizens armed. But that option is not available. In the event that private gun ownership were outlawed, who would actually be most likely to follow the law, and who would be most likely to break it?

The group most likely to follow the law would be those who own a gun for self-defense or recreation. The group most likely to break the law would be those who own a gun for criminal purposes. Why? Criminals, to put it lightly, have a lesser average level of respect for law than the rest of us. A man who is prepared to commit armed robbery or murder is unlikely to pause at the thought of committing a misdemeanor gun law violation. Therefore, restrictive gun laws affect innocent citizens much more than they affect criminals. Criminals may even welcome more restrictive gun laws: surveys show that criminals in America are more afraid of encountering armed victims than they are of encountering the police (and wisely so).[3] Restrictive gun laws help criminals by reducing their chances of encountering armed victims. In other words, they tend to have approximately the opposite of their intended effect.

The popular version of this argument: “If guns are outlawed, only outlaws will have guns.” This is an old argument, and gun control advocates are ready for it. Their response: it isn’t only the criminals we have to worry about. It is ordinary citizens we should worry about. Gun control proponents fear that a perfectly normal, noncriminal person with access to a gun may one day, in the heat of argument with a neighbor or family member, suddenly “snap” and shoot the other party. To support this fear, they cite statistics about the number of murder victims who were killed by someone they knew, or the number of murders that occur after a heated argument.

This argument is a logical and empirical error. When we hear that most murder victims were killed by a family member or someone they knew,[4] this does not imply that they were killed by a normal person as a result of a simple disagreement of the sort that anyone could find themselves in. Remember that the category “someone known to the victim” includes such people as the victim’s drug dealer, the victim’s pimp, one of the victim’s fellow gang members, the victim’s partner in crime. Most homicides are committed by people with prior criminal records, and they are overwhelmingly committed against other criminals.[5] Many are gang-related or drug-related.[6] It isn’t Aunt Sally shooting Uncle Ted in an argument over the phone bill. Even the minority of cases that involve a spouse or family member of the killer do little to support the contention that it is ordinary citizens we need to worry about, rather than criminals. Criminals have acquaintances and family members too. Not surprisingly, people who have a criminal way of life – drug dealers, gang leaders, and so on – are also prone to commit crimes against their own family members, spouses, and so on. This does not show that ordinary people are in danger of shooting their family if they have access to a gun.

For a reality check, ask yourself how often you have seen a normal adult (say, one with no criminal record) punch a friend, acquaintance, or family member in the face as a result of a disagreement. Now consider how much stronger the inhibitions must be against murder than against simple punching, in the mind of a normal adult in our society. Normal people do not kill others because of a family squabble. Criminals with antisocial personality traits and poor impulse control may do so – but they are also the people least likely to actually obey restrictive gun laws.

Gun control advocates believe our society would be safer if no one had guns. Perhaps so – but that is not the relevant question. The question is whether our society would be safer if the people with the greatest disposition to follow the law gave up their weapons, and the people with the least inclination to obey the law kept theirs.

Conclusion

To summarize the main line of reasoning:

Premise 1: It is permissible to violate an individual’s rights only if, at minimum, doing so prevents harms many times greater than the harm it causes to that individual.

Comment: This is supported by the example of the jury convicting the innocent man to prevent riots. There are many similar examples. Some believe, in fact, that it is never permissible to violate certain rights; that view is compatible with (but stronger than) premise 1. Premise 1 only rules out that a rights violation could be justified by its preventing harms only modestly greater than the harms it causes – and this is something that any believer in rights accepts.

Premise 2: Gun prohibition violates the self-defense rights of individuals, causing some of them to be seriously harmed or killed.

Comment: The claim that gun prohibition will result in some citizens being harmed or killed is an uncontroversial empirical claim; many surveys show that self-defense uses of firearms are very common in the U.S. The claim that gun prohibition would be a rights violation is supported by the example of the accomplice who seizes a victim’s gun right before a murderer kills the victim.

Intermediate conclusion: Gun prohibition is permissible only if, at minimum, it prevents harms many times greater than the harms it causes.

Premise 3: Gun prohibition will not prevent much greater harm than it causes.

Comment: There is a great deal of complex and mixed data on this that cannot be reviewed here. Here, I have focused on one main point: that in America, gun prohibition is not likely to succeed in keeping guns out of the hands of criminals; its largest effect will be on the behavior of innocent citizens. Thus, whether gun prohibition would even prevent more harm than it caused is at best unknown; it cannot reasonably be claimed that it would prevent many times more harm than it caused.

Conclusion: Gun prohibition is impermissible.

Notes

[1] Madeleine Morgenstern, “How Many People Own Guns in America? And Is Gun Ownership Actually Declining?”, The Blaze (Mar. 19, 2013), http://www.theblaze.com/stories/2013/03/19/how-many-people-own-guns-in-america-and-is-gun-ownership-actually-declining/; U.S. Census Bureau, “Quick Facts: United States”, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/00.

[2] CBS News, “Number of households with guns on the decline, study shows,” Mar. 10, 2015, http://www.cbsnews.com/news/number-of-households-with-guns-on-the-decline-study-shows/.

[3] James D. Wright and Peter H. Rossi, Armed and Considered Dangerous: A Survey of Felons and Their Firearms (Hawthorne, N.Y.: Aldine de Gruyter, 1986), pp. 144-6.

[4] Noel J. Riggs and Steve B. Scott, “The Top 5 Murders by Relationship to the Victim in the United States,” Top 5 of Anything (2016), https://top5ofanything.com/list/8a1bf3d1/Murders-by-Relationship-to-the-Victim-in-the-United-States.

[5] Michael Thompson, “Most Murder Victims in Big Cities Have Criminal Record,” WorldNetDaily (Mar. 4, 2013), http://www.wnd.com/2013/03/most-murder-victims-in-big-cities-have-criminal-record/.

[6] Marcus Hawkins, “Putting Gun Death Statistics in Perspective,” About.com (Aug. 1, 2015), http://usconservatives.about.com/od/capitalpunishment/a/Putting-Gun-Death-Statistics-In-Perspective.htm.

The problem here is that people don't vote or cheer politicians based on considerations of what policy is superior but based on how to advertise their values and concerns. Studies show people make different choices if they think their choice really determines what happens. Unfortunately, this is at its worst in gun regulation.

For example, consider the issue of assault weapons. These are the worst guns to ban from a cost/benefit POV since handguns are far easier to conceal, easier to carry multiple guns for more rounds and people end up carrying them for discrete self-defense. I'd love to restrict handgun ownership. Moreover, the so called assault weapons aren't actually more deadly (indeed most mass shooters would be better served with multiple handguns) -- mostly they differ in their military aesthetic. And because of that people care particularly strongly about keeping their assault weapons relative to other gun types. Yet that's the focus of much gun control because people want to signal their moral disapproval of glorifying violence and the culture these assault weapons represent.

Indeed, I believe there are good policy solutions that gun owners would accept but only if they felt that their desire to own guns was respected (difference between I know it's a sacrifice and I'm sorry but it's needed and the attitude that your desire to own a weapon is sick and bad in itself). Unfortunately, I don't know how to get us there because every new tragedy makes policy less relevant and cultural clash more.

If you don't want a gun, you don't have to buy one.

I'm a pretty chilled guy. You do you, leave me and mine alone.

If you want to be part of the rainbow, cool. Just don't push your crap on my kids.

I'll let you in a little secret. You can collect all the weapons you want, and only the criminals will have weapons. Then they'll prey on the people who can no longer protect themselves.