A student of mine once wrote in an essay that it was not her goal in life to be a virtuous person and that what she wanted was to be successful. I found that an unusually clear-eyed statement of what is perhaps a widespread – though often unacknowledged – preference. I would guess that whatever people may dream about, very few dream about becoming a virtuous person. While we may want to correct various flaws, particularly flaws that detract from our wellbeing such as being too anger-prone or impulsive, most of us probably want to be successful, popular, and so on. Why aren’t we more focused on becoming virtuous? Should we be?

One reason we aren’t may be that we think we are already good enough, morally speaking. When it comes to morality and character, we have a tendency to apply (to ourselves) a standard that’s not very high. Thus, we look around and see people who seem much worse than we are – corrupt politicians, for instance, or those who resort to physical violence – and we get assured that we don’t need to improve since we are not that bad. We don’t take the best people we can think of as a model.

That is not how things generally work when it comes to goals such as success. If your best friend from high school is now a famous novelist or the owner of a multi-million dollar company, you are unlikely to ignore that and tell yourself that at any rate, another one of your classmates is an unemployed divorcé who has lost custody of his children and whose mother has disowned him. When it comes to status, it seems, we want more than to be one rung higher up the ladder than the people at the bottom.

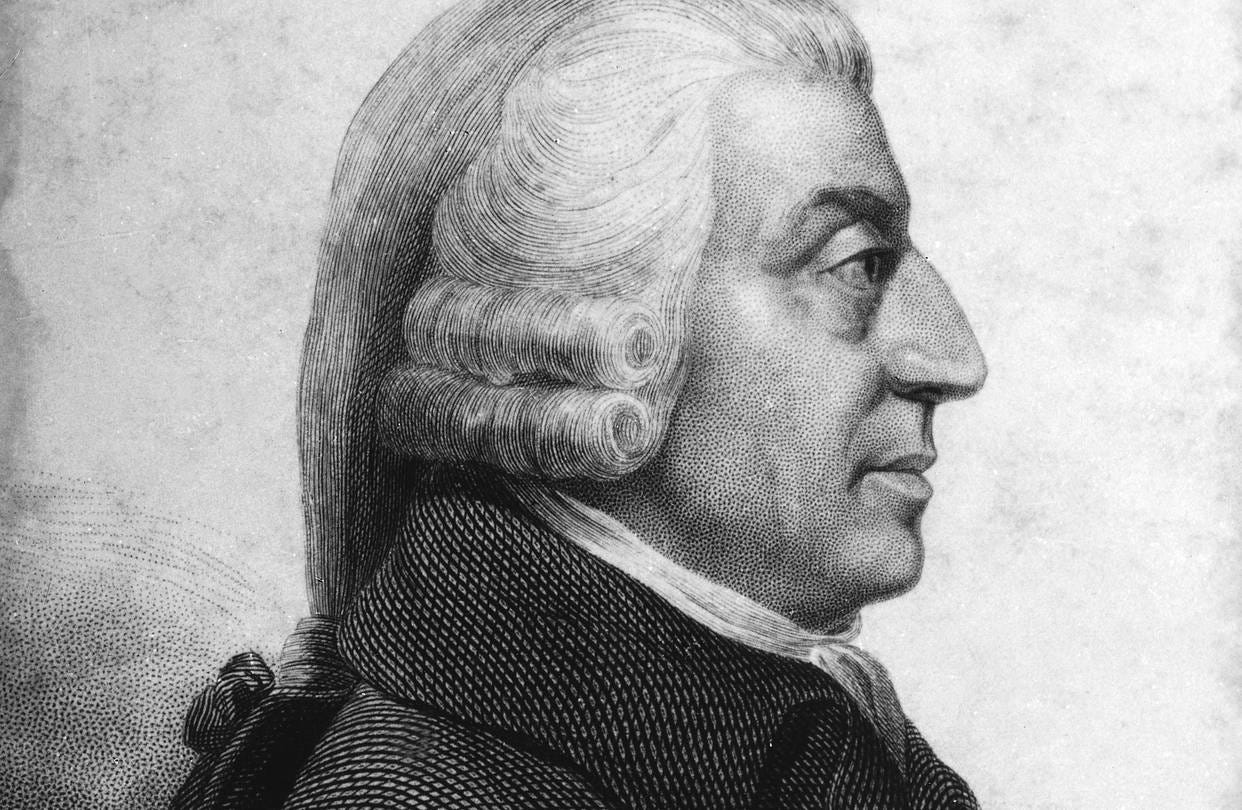

In a section called “On the Corruption of our Moral Sentiments” in The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Adam Smith suggests another reason why we prefer rank to virtue. He observes that social rank and status get more respect than wisdom and virtue do. The two kinds of respect – moral and, for lack of a better word, social – are not the same, but they are frequently conflated, in his view:

Two different models, two different pictures, are held out to us, according to which we may fashion our own character and behaviour; the one more gaudy and glittering in its colouring; the other more correct and more exquisitely beautiful in its outline: the one forcing itself upon the notice of every wandering eye; the other, attracting the attention of scarce any body but the most studious and careful observer. They are the wise and the virtuous chiefly, a select, though, I am afraid, but a small party, who are the real and steady admirers of wisdom and virtue. The great mob of mankind are the admirers and worshippers … of wealth and greatness. The respect which we feel for wisdom and virtue is, no doubt, different from that which we conceive for wealth and greatness; and it requires no very nice discernment to distinguish the difference. But, notwithstanding this difference, those sentiments bear a very considerable resemblance to one another … (and) inattentive observers are very apt to mistake the one for the other.[1]

The sort of “corruption” of our moral sentiments Smith talks about may have its roots, at least in part, in aesthetic preferences. Success is somehow more interesting than virtue. Newspapers and magazines abound with stories about celebrities, royals, and so on, not because this is what editorial boards are interested in covering, but because editors anticipate that this is what readers would prefer to read. Such stories are attention-grabbers. While there is clearly a market for stories about good deeds as well, most anyone on the planet can probably name many more celebrities of the traditional sort than exceptionally virtuous people.

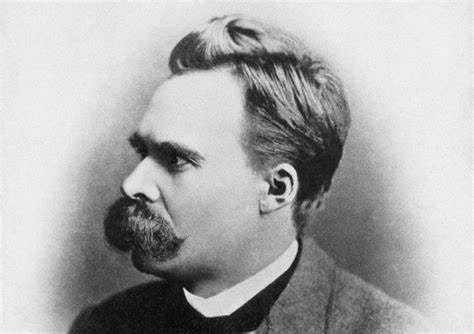

Smith’s analysis can be seen as a counterpoint to a (better known) claim about morality Nietzsche makes: Nietzsche argued that traditional morality, or what he called (unkindly) “slave” morality – Christian virtues such as charity and altruism – is the morality adopted by the masses.[2] Since most people cannot excel, Nietzsche maintained, they downplay the importance of excellence. Smith suggests, by contrast, that something quite different is true: Most people do not extol charity and altruism but rather, worship a certain kind of flashy “greatness” and even tend to see greatness as a moral merit.

Smith’s description probably captures the world today better than Nietzsche’s. (Though things are complicated. For instance, we have the phenomenon of “virtue signaling,” which can be seen as an attempt to get social status – rather than moral respect and self-respect – by persuading others of one’s own virtue.) What would the world be like if our sentiments did not get systematically distorted in the ways Smith describes, and we chose virtue? Would it be better, all things considered?

The answer to this question is not clear. I discuss the connection between virtue and consequences elsewhere,[3] but in general, the answer depends on what benefits would accrue to society if people aimed primarily to be virtuous. Would it be better if a gifted singer spent her time on helping others and otherwise cultivating her character rather than on developing her talents? If a gifted engineer did? In some ways, yes, surely. All things considered? Probably not.

We may, perhaps, say that what a person should aim for is to align the goals of success and virtue. It is probably possible to do this, because anyone who aims to succeed by engaging in a socially desirable activity (rather than a criminal activity) is generally pursuing a goal that it is good to pursue. It is just that a person’s own motivation is typically self-interested. It is highly desirable that there be great singers, scientists, and engineers, and aiming to bring about a socially desirable outcome is in principle morally good. However, individual people who try to succeed are attempting to achieve something chiefly for themselves, not for society: a scientist may, thus, want to be the first to publish a paper defending some idea, though from the viewpoint of society, it doesn’t matter who was first (Newton was upset that Leibniz published work on calculus before Newton himself[4]), and a singer wants to sell more albums than a rival though that’s a purely self-interested goal as well. Maybe, what we need is to continue aiming for success but to do it for morally better reasons, that is, because and to the extent that our personal success will bring about some social good.

I doubt that this strategy would work. By and large, we cannot directly choose our motivation even if we wanted to, and here, it is probably not advisable to try: trying may do nothing more than undercut people’s actual motivation to apply themselves. In addition, a human society should encourage self-realization and the individual pursuit of happiness when the consequences – whatever one’s motivation – will be socially desirable. We want a society of happy people.

However, Smith’s original point about respect stands: There is nothing specifically morally praiseworthy about the pursuit of one’s own individual goals. This pursuit is perfectly permissible and often desirable from a social point of view. Success may bring well-deserved accolades and recognition, but only virtue is worthy of moral respect.

Interestingly, Kant suggests that at some level, we all already know this. In a passage in his Critique of Practical Reason, he observes that we can’t help but feel moral respect for a person more virtuous than we are. And he goes on to make the intriguing claim that superior virtue in a person of a lower social status may occasion a sort of unease in someone of a higher social status. He writes:

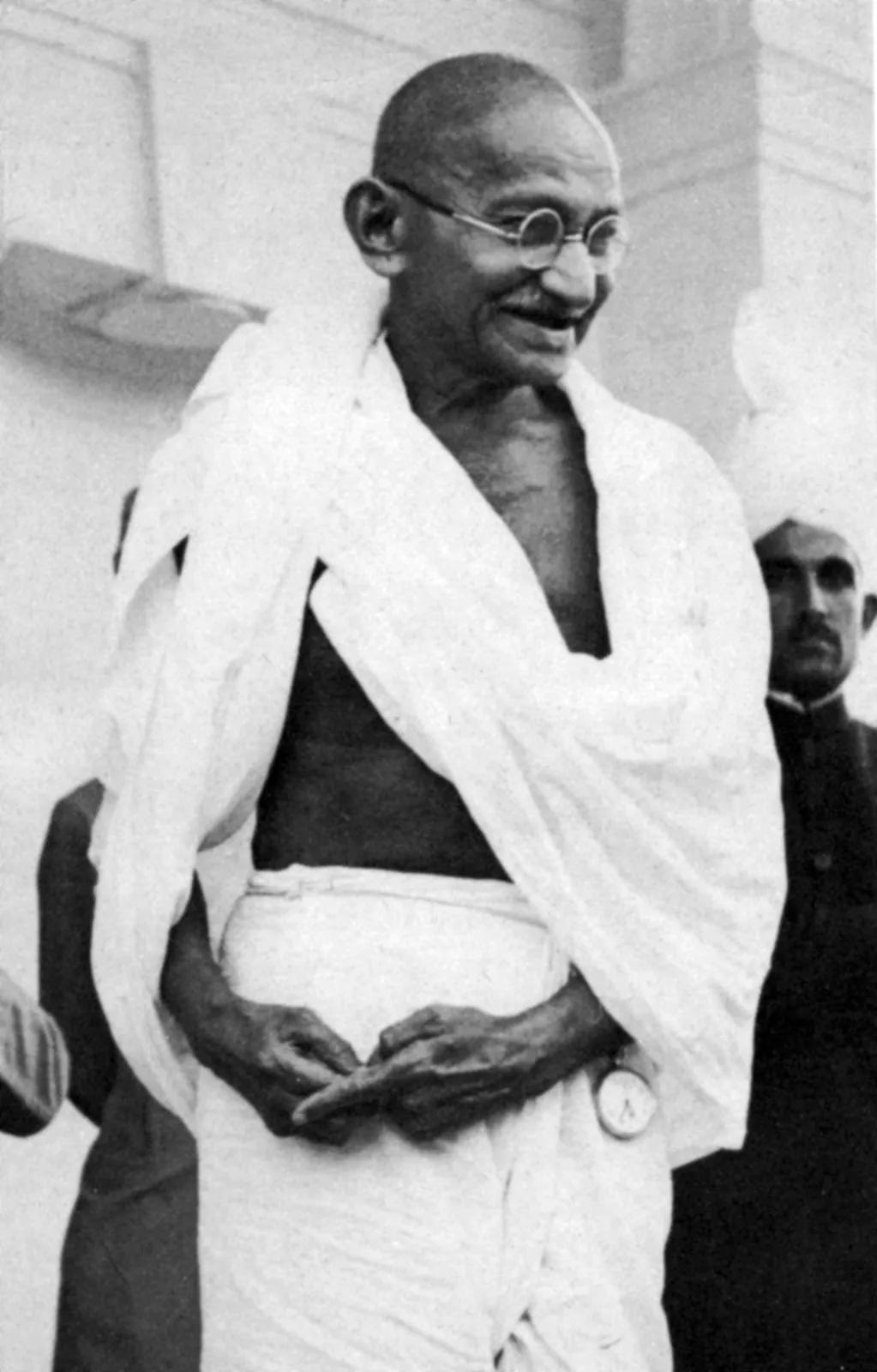

Fontenelle says, “I bow before a great man, but my spirit does not bow.” I would add, before a humble plain man, in whom I perceive uprightness of character in a higher degree than I am conscious of in myself – my spirit bows whether I choose it or not, and though I bear my head never so high that he may not forget my superior rank. Why is this? Because his example exhibits to me a law that humbles my self-conceit when I compare it with my conduct … Respect is a tribute which we cannot refuse to merit, whether we will or not; we may indeed outwardly withhold it, but we cannot help feeling it inwardly.[5]

There is clearly something to Kant’s point as well. While on some occasions, we may be apt to confuse the admiration for greatness with moral respect, as Smith argues, in more reflective moments, we know the two are not the same thing. Indeed, we know that moral qualities are, in some important sense, weightier. A person better than the rest of us at singing, or physics, or engineering, even if very much better, is yet better only in some (non-moral) respect. A more virtuous person, on the other hand, is better overall: a better person. We know this whether or not we make it our goal to pursue virtue, that is, to be better people.

[1] Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (Liberty Fund, 1982), I.III.2.

[2] Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morality (Hackett, 1998).

[3] Iskra Fileva, “What Does Virtue Have to Do with Consequences?”, Oxford Studies in Normative Ethics, Vol. 13 (Oxford University Press, 2023), pp. 235–52.

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leibniz–Newton_calculus_controversy.

[5] Immanuel Kant, Critique of Practical Reason (Cambridge University Press, 1997), pp. 76–7.

Beautiful essay. I thought of Pip and Joe in Great Expectations as an excellent literary illustration of the distinction between material and moral virtue.

These themes of status and success and morality are ones I'm deeply interested in exploring.

This is very interesting. I think "virtue" is a lost word in our age and the article does an effective critique on it, but I think 'virtue' requires deeper analysis than either the greatness/virtue-as-morality dichotomy suggests. The word has become domesticated by moral philosophy, but virtue is fundamentally about excellence - and excellence is always tied to our understanding of being itself. It is not a dichotomy.

Historically, this is clear. The root 'vir' originally signified the excellence proper to human nature - what we might call virile excellence, the courage to act decisively in the world. Nietzsche was right that Christianity transformed this: the warrior-hero who ventures forth became the saint-martyr who suffers for others. This wasn't just a change in values but in our conception of what constitutes higher being. The Greeks captured this with 'arete' - excellence oriented toward flourishing. But here's what's crucial: such excellence always involves orientation toward what a culture recognizes as ultimately valuable. The warrior's courage made sense within a cosmology that saw decisive action as reflecting divine power. Christian virtues made sense within a cosmology that saw self-giving love as reflecting divine nature.

This brings us to the deeper question: what is the nature of virtuous existence (not merely a single act) for a person? What makes virtue virtuous for a person? We must go beyond mere objectivity and beyond formulations that treat the person as if they were not a person and their free orientation were not free. This is quite a serious and complicated question that needs a serious analysis. As serious as can be done in comment, so bear me with me:

Virtue as the fundamental guide of proper action involves the entirety of the person's existence and is oriented towards what one recognizes as most excellent. But we cannot avoid the fact that this orientation constitutes, functionally, a form of worship - the subject bows down to the object of virtue. All virtue entails subordination to what is deemed sacred. This is reinforced by this being about the entirety of the person's existence. We may even call this orientation towards an other love.

Here we encounter Nietzsche's insight in full force. When this bowing down is directed toward an external impersonal object, it becomes a barely veiled form of totemism. The subject delivers their own subjectivity to something that cannot recognize their subjectivity in return. This destroys the very practical nature that makes the act meaningful in the first place. Consider what happens functionally: when I subordinate myself to an impersonal moral law or objective standard, I must treat myself as an instrument for realizing goods that remain indifferent to my existence as a person. I become a replaceable functionary - what matters is only that the impersonal good be instantiated, not that I as this particular subject realize it. But this is self-destructive. An object cannot be virtuous - only subjects can be. Yet this supposed virtue systematically eliminates subjectivity itself. The 'virtuous' person becomes someone who has successfully objectified themselves.

But clearly, justified virtue-orientation for persons cannot consist in self-objectification. This personal free decision must affirm rather than destroy personhood and freedom. The orientation of proper existence cannot be love of objects. A much proper orientation, both by analysis and basic intuition, is love of people - personal love. Yet if I simply deliver my existence to another person, I risk the same objectification. Consider what happens when I decide to always obey another person. Even though this other is a subject rather than an impersonal principle, they can still deny my subjectivity and objectify me. This would be enslaving rather than virtuous. So how can virtue be?

The problem is principled. Finite subjects, however well-intentioned, can by nature fail to recognize and preserve my subjectivity in their demands upon me. The act of delivering my subjectivity to a loved person can never be known beforehand whether it will succeed to be either virtuous or enslaving by itself. Adding an impersonal mediator per the above cannot perform this function either in itself. A question arises here: would selfishness be virtuous? Can't the person be virtuous by orienting towards itself? The classical individualist self-fulfillment? Most of us recognize not. Selfishness is a vice and it's not excellent nor leads to flourishing, but is corruptive. But why? Few analyze this, but it seems clear under this analysis: it fails to recognize that mutual recognition is required because the self is not complete, which is why we are always acting in relation to an otherness. If the otherness is merely objects and not subjects, then we receive only objectivity in return, which does not sustain ourselves as subjects. It is objectivizing.

How then is virtue possible? If neither impersonal nor human (in a qualified sense) nor self orientation works can succeed for the same fundamental reason: it is an act of deliverance of my personhood which objectivizes? The main insight, after this analysis, seems to be that virtue is only possible if our act of orientation of our subjectivity is sustained by an actual Person who in principle can never objectivize me and who always fulfills my subjectivity and enriches it. It is neither excellence nor morality. It is to recognize that they are united: excellence and the other are essentially united in the very essence of personhood so that self-actualization requires and is constituted by love and service. Both the intuitions of recognizing our personhood and of the inherent other-relatedness of existence are proper, justified and fundamental. No compromise is neither possible nor desirable.

I am open to refutation, but think my analysis is quite systematic and solid.