[ This is a guest post by Matthew Adelstein, who, in my opinion, is among the best philosophy students in the world, possibly the best. He also has a blog. —mh ]

1 Introduction

Utilitarians say that you should take whatever action maximizes total well-being for everyone. This is intuitive in most cases; if you can help John a bit or Theresa a lot, you should help Theresa. However, utilitarianism is controversial, with some ordinarily sensible people—like the venerable Michael Huemer—rejecting it. One case where utilitarianism is counterintuitive is the famous footbridge case, or, Bridge.

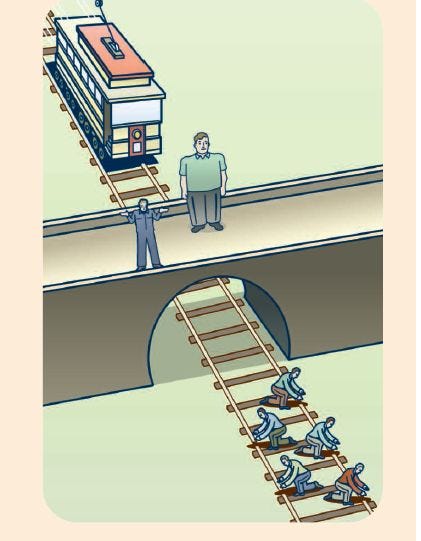

Suppose a train is heading under a bridge, towards five people, about to run them over. The people can’t be moved out of the way. On the bridge is a rotund gentleman who is so large that he could stop the train if you push him off the bridge. Assume you would get away with it, it wouldn’t destabilize broader trust in society, etc.

Common sense suggests that you shouldn’t push the guy off the bridge. You’d be killing someone! Yet utilitarianism holds that pushing him off is the right thing to do. Who is right?

Here, I’ll argue that utilitarianism is right. I’ll argue that the judgment that you shouldn’t push the guy off the bridge is even more counterintuitive than the judgment that you should. (For a fuller account, see here.)

2 Good to Happen, Good to Do

Rather than thinking just about what you should do, let’s ask: would it be good if the man simply fell off the bridge? (Suppose that a gust of wind or a particularly powerful moral fact blew him off the bridge.)

It seems the clear answer is yes. In this case, no one’s rights would be violated, but one person would die instead of five. It’s worse when five people die than when one does, so if the man fell off the bridge naturally, that would be a very good thing.

Here’s a plausible principle: if it would be good if X happened, you should do X (assuming it doesn’t trade off against doing other things). For example, if it would be good if John was pulled out of the ditch he’s in, then you have a reason to pull him out of the ditch.

If this is right, because it would be good if the man fell off the bridge, then you should make him fall off the bridge. So you should push him.

Probably those perversely opposed to pushing people off bridges would simply deny the principle. Yet the principle is quite intuitive. It would be odd to think that though you should want a gust off wind to push the person off the bridge, you shouldn’t do it yourself. Furthermore, because it’s more abstract and intellectual, the principle is less likely to be subject to error. While culture and evolution give us more specific advice about concrete scenarios—thus potentially biasing us—these abstract intellectual intuitions are more plausible candidates for pure deliverances of reason.

Here’s another weird consequence of the anti-pushing view: sometimes it’s bad when perfect people are put in charge of things. For example, suppose that currently a perfectly moral person is asleep. They were given a sleep potion so that their muscles are all maximally tense in a way such that if they were awake, they’d have to exert immense effort to keep them sufficiently tense. They’re being swung by a rope so that they’ll knock the man off the bridge. However, they’ll only knock the man off the bridge if their muscles are tense.

The anti-pushing view implies it would be a very bad thing if they were to wake up. Upon waking, they’d have to exert immense effort to make sure they push the person, while if they remain asleep they’ll naturally push them. Because the view holds it’s wrong to push the person, if they wake up, something terrible will happen—five extra people will die, as they won’t continue tensing their body so that the person is pushed. But surely it can’t be bad to put a perfectly moral person in charge of a process. Putting people who do the right thing in charge shouldn’t make things worse.

3 Undoing Wrong Things

Here’s another plausible principle: suppose you do something wrong. Before it’s had any effects, you can undo it. Seems that you should. Things that shouldn’t be done should be undone.

But now suppose that you have pushed the man off the bridge. Before the train has hit him, you can pull him back up to the top off the bridge, so that the train will hit the five people rather than him. It seems wrong to do that. But that action would simply be undoing the original action.

Thus: You should undo an action if it’s wrong, but you shouldn’t undo pushing the man off the bridge, so pushing him off the bridge isn’t wrong.

There are two ways to get around this. First, you can think you sometimes shouldn’t undo wrong actions at no cost. Yet this seems highly bizarre and implausible—definitely a cost of the no-pushing view.

Second, one could hold that you should undo the action and pull the person back onto the bridge. Aside from just seeming implausible, this view has an even worse consequence. Consider the following case:

Catapult: A train is going to hit five people. You can push a large man off a bridge to stop them from being run over. Not only will the large man stop the train, he’ll fall on a button that will launch the five people out of harm’s way.

Catapult seems relevantly similar to Bridge. The only difference is that if you push the man off the bridge, in Catapult, the people saved will also get launched to safety. However, that doesn’t matter at all because they’re safe either way. So we can make the following argument:

If you shouldn’t push the person in Bridge, you shouldn’t push the person in Catapult.

If you shouldn’t push the person in Catapult, you should undo your action if you push the person in Catapult.

You shouldn’t undo your action if you push the person in Catapult.

So it’s false that you shouldn’t push the person in Bridge.

I’ve already discussed premises 1-2. So the only premise in doubt is premise 3. But premise 3 seems extremely obvious. Undoing Catapult involves moving one person onto a bridge, saving his life, while also moving five people onto the train tracks, so that they die instead. Surely that’s wrong!

It’s even more obvious if we add a long time delay. Suppose that the train takes 100 years to arrive and all the people will be in comas for 100 years. In the year 1920, you pushed the person off the bridge in the catapult scenario. Then, 95 years later, you can undo Catapult before your action has affected anyone—moving the five people you saved back onto the track while moving the one person away (assume you have to either do both of these things or do neither). It seems obviously wrong to do that.

4 The Big Guns (Suitcases!)

Let’s modify Bridge so that there are six people—conveniently named p1, p2, p3, p4, p5, and p6—who are all in suitcases, and you don’t know which persons are in which suitcases. One suitcase is on the bridge, while five are on the tracks. If you push the top suitcase, you’ll kill the person in it but save the others. You have no idea who is in the top suitcase. Call this case Suitcases. I claim:

You should push the person off the bridge in Suitcases.

If you should push the person off the bridge in Suitcases, you should push the person off the bridge in Bridge.

Therefore, you should push the person off the bridge in Bridge.

I have two arguments for (1). First: pushing the suitcase is better for everyone in expectation. Every single person—p1, p2, p3, p4, p5, and p6, none of whom know their positions—would want you to push the person in the suitcase on top of the bridge, for it reduces their risk of dying from 5/6 to 1/6.

Second—and bear with me, for this case is about to get a bit complicated (it’s not original to me)—imagine there’s a second, parallel track with six suitcases, one on top of the Bridge, five below the bridge. Each suitcase on the parallel track is filled with sand rather than people and a train is heading towards it.

So to recap, there are two trains, 6 people on one side of the track, with one on top of the bridge, and 6 suitcases of sand on the other side of the track with one on top of the bridge. If you do nothing, the five people on the one track and the five suitcases of sand on the other will all be hit and the people will die.

Now suppose that there are six buttons: button 1, button 2, etc.

Button 1 does two things:

(i) It switches out person p1 with the parallel sand suitcase. So, for example, if p1 happens to be nearest to the right on one track, button 1 would make p1 trade places with the sand suitcase nearest to the right on the other track. If p1 happens to be on top of the bridge, button 1 would swap out person one with the sand suitcase on top of the bridge.

(ii) It knocks the suitcase on top of the bridge on the sand suitcase side off the bridge so that it stops the train from hitting the other five suitcases.

It seems you should push button 1. After all, button 1 doesn’t affect anyone other than p1 and it reduces p1’s risk of death from 5/6 to 1/6—instead of p1 dying if she is in any of the bottom five suitcases, now she will only die if she’s in the top suitcase.

Button 2 swaps out p2 with the parallel sand suitcase, button 3 swaps out p3, and so on. It seems by the same reasoning, you should push buttons 2-6.

If you should press all the buttons individually, then if there was a single button that simply had the effect of pressing all six buttons, you should press that button. But that button would simply move the people over and push the person off the bridge. Thus, because you should press every button, and the buttons together simply push the person off the bridge, you should push the person off the bridge.

So far I’ve argued that you should push the person off the bridge in Suitcases. Now I’ll argue for the second premise, “If you should push the person off the bridge in Suitcases, you should push them off the bridge in Bridge.” There are four good arguments for this.

First, suppose that you push the person in Bridge with your eyes closed, never seeing them, so you don’t know whom you’re pushing. It seems like if it’s fine to push the suitcase in Suitcases, then it’s fine to push the person in Bridge if your eyes are closed—in each case, everyone is better off in expectation. But if it’s fine to push the person with your eyes closed, then it’s fine to push them in Bridge with your eyes open.

Second (as argued by the brilliant Caspar Hare) suppose you should push them when they’re in suitcases but not if you can see them and they’re outside of suitcases. How much about them do you have to know for it to be wrong to push? Suppose that the person’s ear pokes out of the suitcase—you can see the ears of everyone involved but nothing else. Should you push them then? Knowledge about people comes in degrees, and any threshold delineating an amount you need to know about the person in the suitcase before it’s wrong to push them is arbitrary and implausible.

Third (per Kacper Kowalczyk’s excellent paper) imagine that all the people are in suitcases at 12:00. However, by 1:00 they’ll have exited the suitcases. You have the option to push the person at either 12:00 or 1:00. Suppose additionally that everyone will be better off if you push them at 1:00 than 12:00—perhaps the person in the top suitcase will scream for the hour if you push them at 12:00, leaving everyone greatly traumatized. This view implies that you should push them at 12:00 but not 1:00, even though everyone would be better off if you push them at 1:00.

Fourth (per Ryan Doody’s paper), on this view, it’s very bad to see into the suitcase and witness the identities of the people, for when one does so, they’ll no longer be able to permissibly take an action that saves four lives on net. This seems to imply that it would be very good, if one was about to be forced to peek into the suitcases, to blind oneself so one couldn’t see the people’s identities. This is highly counterintuitive.

Thus, premise 2 is also on firm ground. If both premises are right then you should push the large man off the bridge. This is a bit counterintuitive, but the truth often ends up being a bit counterintuitive. In this case, we have several powerful converging lines of argument for revising the verdict of common sense.

I subscribe to Adelstein's Substack, so I feel a bit shortchanged to have to give up some Huemer to get more Adelstein. Adelstein is so prolific I can’t keep up with his output. Huemer is so interesting that I would like to have more than I can handle.

I think critics of utilitarianism can quibble with these sorts of thought experiments and intuition pumps on their own terms. But they always silently side-step my major objection, which has to do with the epistemic aspect of the assumptions. An agent who is perfectly well informed about the consequences of their actions would be justified in at least being tempted by a version of utilitarianism. The situation is not clear for ordinary agents, or if it is clear, it is clearly in opposition to even fairly complicated and sophisticated utilitarianism. In a slightly more realistic scenario, there is a non-zero probability that pushing the fat man will make things worse, perhaps resulting in his death together with the five persons in danger. With that slight reframing of the thought experiment, the conclusion is reversed. Perhaps the basic concept remains, but only when agents have sufficiently strong confidence in their understanding of a situation. Such situations might exist, but tend to be of small importance.

Still working through your undoing and suitcase cases, but I’m not persuaded by the arguments preceding those cases.

Background: I am myself unsure about the normative theoretical truth, but I find it plausible that there are (moderate) deontological constraints against certain sorts of actions. That’s to say, it seems to me there are cases in which an action would bring about more utility (or whatever constitutes value simpliciter) than refraining from it, but is nevertheless wrong. That’s mostly a matter of intuition, not inference. I have that intuition about actions like murder, including actions like pushing the person in the footbridge case. That’s why I hesitate to affirm the morality of that action.

That hesitation isn’t reduced by reflecting on the principle that “if it would be good if X happened, you should do X (assuming it doesn’t trade off against doing other things)”, nor by reflecting on claims like “it can’t be a bad thing to put a perfectly moral person in charge of a process” and “Putting people who do the right thing in charge shouldn’t make things worse”. I’ll explain why.

Re the principle that “if it would be good if X happened, you should do X (assuming it doesn’t trade off against doing other things)”. The sorts of deontological intuitions I have about cases of murder – including in the footbridge case – seem to undermine it. E.g., suppose an elderly tenant in a lodging house is not a happy person, and is somewhat ornery to boot, slightly decreasing the happiness of the other people in the house. Two possibilities: (a) he lives another ten years, or (b) a bottle of poison accidentally falls over and spills into his evening tea, killing him tonight. Suppose total utility is slightly higher if (b) than (a). If I understand the principle correctly, it follows that – putting aside irrelevancies, and assuming an accident isn’t in the cards – you should poison him. But that evokes the very sort of anti-murder intuitions that make me hesitate to affirm pushing in the footbridge case. Maybe they’re inaccurate, but my point is that the principle doesn’t seem to add to the case for pushing.

Re the claims that “it can’t be a bad thing to put a perfectly moral person in charge of a process” and “Putting people who do the right thing in charge shouldn’t make things worse”. Insofar as I find constraints against murder plausible, I find it plausible that perfectly moral people would refrain from murder in some cases in which murder would maximize utility. Indeed, the intuition that perfectly moral people would do that is identical to the very intuitions favoring the anti-murder constraint in the first place, with the additional stipulation that the agent involved is morally perfect. So again, it doesn’t seem like anything has been added that might bolster the case for pushing the person in the footbridge case.