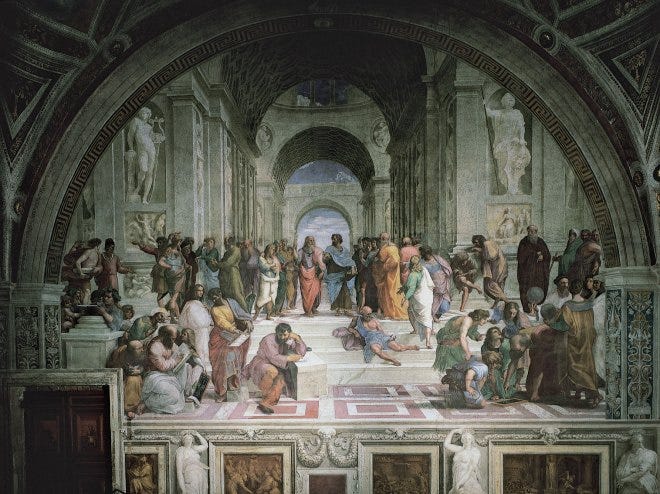

Some of you might know that there is a split in contemporary philosophy between "analytic" and "continental" styles, but not know what this split is about, or why analytic philosophy is better. This is to remedy that.

I. About Analytic Phil

Analytic philosophy is mainly written in the English-speaking countries (England, America, etc.). Think of people like G.E. Moore, Bertrand Russell, A.J. Ayer, and most people in the high-ranked philosophy departments in the U.S. today.

"Analytic" philosophers used to be people who thought that the main task of philosophy should be to analyze language (explain the meanings of words), or analyze concepts. But now they are basically just people who do philosophy in a certain style (regardless of their substantive views).

What is that style? There is generally a fair attempt to say what one means clearly, to give logical arguments for one's theses, and to respond (logically) to objections to one's arguments.

Also, there is still a fair amount of attention paid to questions about the meanings of words, or the logical and semantic relations among concepts, that are of philosophical interest. If an analytic philosopher is discussing justice, you can usually expect discussion of such things as the meaning of "just"; how the concept of justice relates to such concepts as those of fairness or rightness; etc.

II. About Continental Phil

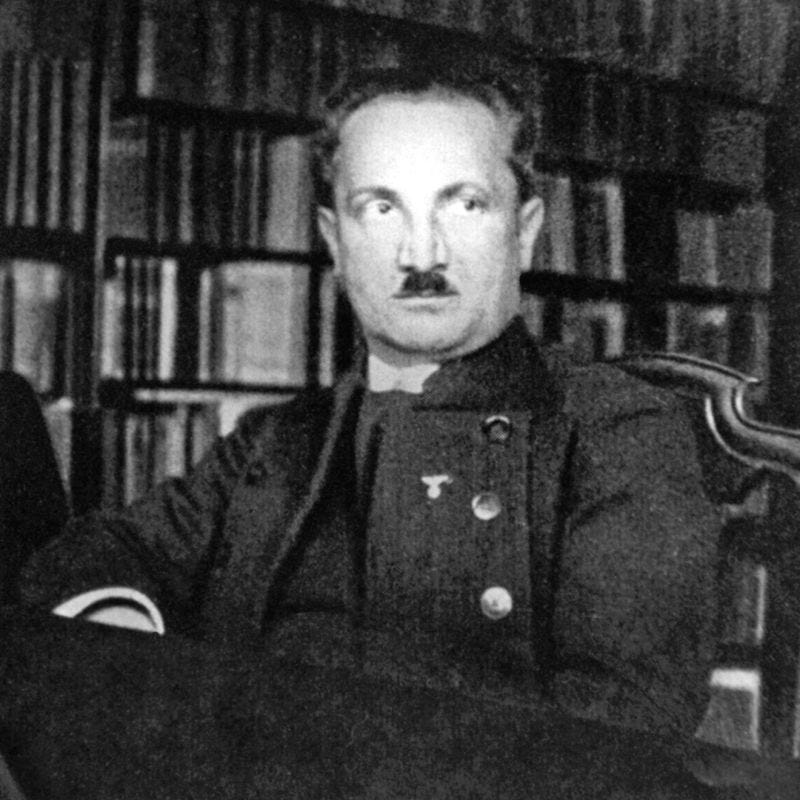

Continental philosophy mainly comes from continental Europe, especially France and Germany. Think of people like Heidegger, Foucault, and the existentialists.

The style is largely the opposite of that of analytic phil. Continental writers are generally much less clear about what they're saying than the analytic philosophers. They won't, e.g., explicitly define their terms before proceeding. They use more metaphors without any literal explanation, and they use more idiosyncratic, abstract jargon.

When they advance an idea, they sort of give arguments for it, but it's hard to isolate specific premises and steps of reasoning. A continental author would never tell you that he has three premises in his argument, and then write them down as statements (1), (2), (3) (as analytic philosophers often do). You also would find a lot less effort to directly address objections or confront alternative theories. They say things that are supposed to lead you along a line of thought. It's just that at the end, it's very hard to answer questions like "How many premises were there?", "What was the 2nd premise?", and "What was the first objection?"

There are also certain doctrinal themes. Works of continental philosophy are much more likely than analytic philosophy to communicate some kind of subjectivism or irrationalism. That is, you are more likely to find passages that (when you sort of vaguely figure out what they might be saying) seem to be arguing that reality depends on observers, that it is not possible or not desirable to think objectively, or that it's not possible or not desirable to be rational.

Philosophers generally tend to lean to the left politically. But Continental philosophers tend to lean very far left (more so than other philosophers).*

*Aside: Heidegger, a scion of Continental philosophy, was literally a Nazi, which is a "right-wing" view. So a more complete statement would be that continental philosophers are more likely to hold crazy and horrible extreme political views, like communism and fascism.

III. Carnap v. Heidegger

One can't mention the analytic/continental divide without mentioning the disagreement between (continental philosopher) Martin Heidegger and (analytic philosopher) Rudolf Carnap. In "The Elimination of Metaphysics through Logical Analysis of Language," Carnap discusses nonsensical utterances that can be made in natural language (http://www.ditext.com/carnap/elimination.html). He gives as an example the following excerpts from Heidegger:

What is to be investigated is being only and—nothing else; being alone and further—nothing; solely being, and beyond being— nothing. What about this Nothing? . . . Does the Nothing exist only because the Not, i.e. the Negation, exists? Or is it the other way around? Does Negation and the Not exist only because the Nothing exists? . . . We assert: the Nothing is prior to the Not and the Negation. . . . Where do we seek the Nothing? How do we find the Nothing. . . . We know the Nothing. . . . Anxiety reveals the Nothing. . . . That for which and because of which we were anxious, was 'really'—nothing. Indeed: the Nothing itself—as such—was present. . . . What about this Nothing?—The Nothing itself nothings.

(Note: that is much clearer than most of Heidegger's writing.)

Carnap goes on to explain (using predicate logic) how in a logically proper language, such statements could not be formulated.

IV. Analytic Philosophy Is Obviously Better

Many people interested in Continental philosophy are perfectly nice people. That said, analytic philosophy is obviously better. Why?

A. Style

My description above of the difference between the two schools should make it clear why I say analytic phil is better. These things:

Clear theses

Clear, logical arguments

Direct responses to objections

I would say are the main virtues of philosophical (or other intellectual) writing. And by the way, I don't think my description of the difference between Continental and Analytic Phil is very controversial. I think almost anyone who looks at samples of the two kinds of work is going to notice those three differences.

Why are those things important? Because (and I assume this without argument) philosophical work has a cognitive purpose. The purpose is to improve the reader's knowledge and understanding of something. The purpose is not, e.g., to confuse people, to impress people with your vocabulary, to enjoy the contemplation of complex sentence structures, or to induce people to shut up and stop questioning you.

For a work to increase the audience's knowledge and understanding, it is generally necessary that the reader understand what the work is saying. Therefore, clear expression is a cardinal virtue of philosophical writing.

Also, to increase a reader's philosophical knowledge and understanding, one generally has to give the reader good reasons for believing what one is saying. That is because, in most cases, philosophical ideas that are worth discussing are not so self-evident that readers can be assumed to see their truth immediately upon their being stated. Usually, one's main thesis is something that other smart people would disagree with.

Thus, if the reader is going to rationally adopt your position, they will generally need reasons. Also, they will generally need to understand what is wrong with the main objections that other philosophers would raise. If, instead, they adopt your view because of your rhetorical skill, because they're impressed with your sophistication, because you've confused them too much for them to think of objections, etc., then they will not have acquired knowledge and understanding of the subject.

So, giving logical arguments and responding to objections are also cardinal virtues of philosophical work.

You might think this is all trivial and in no need of being explained. But it appears that many people (who prefer the Continental over the Analytic style) don't appreciate these points.

B. Doctrines

The other thing to point out is that the substantive doctrines most commonly associated with continental philosophers are false.

(1) There is an objective reality.

For example, when you close your eyes, the rest of the world doesn't pop out of existence. The world was around long before there were humans (or even non-human observers). The Earth has been here for 4.5 billion years, whereas human observers have only existed for 20,000 - 2 million years (depending on what you count as "human"). Therefore, the world doesn't depend on us.

What's the objection to this? As far as I can tell, there is one main argument against objective reality. A version of it first appeared, as far as I know, in Berkeley. Berkeley's argument was something like this (my reconstruction):

If x is inconceivable, then x is impossible. (premise)

It is not possible to conceive of a thing that no one thinks of. (premise)

Explanation: if you conceive of x, then you're thinking of it.

Therefore, [a thing that no one thinks of] is inconceivable. (From 2)

Therefore, [a thing that no one thinks of] is impossible. (From 1, 3)

If there were objective reality, then it would be possible for there to be things that no one thinks of. (From meaning of "objective")

Therefore, there is no objective reality. (From 4, 5)

(David Stove refers to this argument as "the Gem", and he has awarded it the prize for the Worst Argument in the World.)

Here, I will just point out the equivocation in (2). In analytic speak, it's a scope ambiguity. The problem is that 2 could be read as either 2a or 2b:

2a. Not possible: [For some x,y, (x conceives of y, and no one thinks of y)].

2b. Not possible: [For some x, (x conceives: {for some y, no one thinks of y})]

Reading 2a is needed for the premise to be true, but reading 2b is needed for 3-6 to follow.

Usually, the argument for subjectivism is stated a lot less clearly. Usually, people say something that sounds more like this:

"It's impossible for us to know anything without using our minds/conceptual schemes/perceptions/etc. Therefore, we can only know things-as-we-conceive-them/as-we-perceive-them/as-our-minds-represent-them/etc. Therefore, it makes no sense to talk about things as they are in themselves. Therefore, the idea of 'objective reality' just makes no sense; it's meaningless."

I'm doing my best to make sense of the sorts of arguments I've heard and to make them sound sort of logical, but when you hear actual subjectivists talk, it's usually much less clear than that. (Bishop Berkeley was actually the clearest subjectivist.)

Anyway, the above statement is essentially a (more muddled) version of the Gem, and it basically has the same mistake. The mistake is confusing the statement that a given object of knowledge is represented by a particular mind with the idea that its being represented by that mind is part of the content of the representation.

In other words: I can only imagine the Earth when I'm imagining it. It doesn't follow from this that I can only imagine the Earth as being imagined by me. I.e., it doesn't follow that I can't picture the Earth being there back when I wasn't around. (And it would be very silly to deny that I can do that.)

(2) Be rational & objective.

I'm not going to discuss at length why you should think rationally. I think that's basically a tautology. (Rational thinking is just correct thinking. If there was a good reason for 'not being rational', that would just prove that the thing you're calling 'not being rational' is in fact rational.)

But I am going to just comment on what's going on when a thinker starts attacking rationality or objectivity. To be fair, few people will outright say, "Hey, I'm irrational, and you should be too!" (Mostly because "irrational" sounds like a negative evaluative term.) But you can hear people rejecting central tenets of rationality, such as that one should strive to be objective and consistent.

So here's what I think is going on when that happens: the thinker knows that he himself is wrong. He doesn't know this fully explicitly, of course; he is self-deceived, and is trying to maintain that self-deception. If you're wrong, and you want to keep holding your wrong beliefs, then you kind of implicitly know that you need to avoid thinking rationally or objectively. You also have to avoid letting things be clearly stated. Fog, bias, and confusion are the key things that are going to help you keep holding false beliefs.

(Alternately, the thinker may simply want other people to hold false beliefs, and know that bias and confusion are the keys to making that possible.)

So when I hear someone more or less attacking rationality and objectivity, or trying to avoid clear formulations of ideas, I take that as almost a proof that most of the rest of what that person has to say is wrong.

(Still ahead next week: What's wrong with analytic philosophy.)