Against History

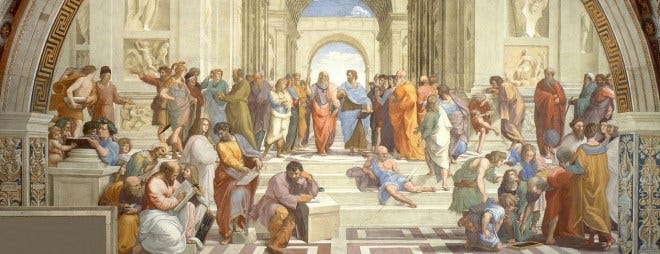

In my previous two posts, I attacked Continental philosophy and Analytic philosophy, respectively. But some philosophers remain unoffended, so now it's time for me to attack the third main thing that people do in philosophy departments: the history of philosophy. I don't understand why we have history of philosophy. I've taken several courses in history of philosophy, and listened to many lectures on it over the years, and occasionally I have raised this question, but no one has ever told me why we have this field.

1. What Is History of Philosophy?

Don't get me wrong. I understand why we read historical figures, and why we cover them in classes -- because the famous philosophers of the past are usually interesting, and they gave canonical formulations of very important views that are often still under discussion today. They also tended to have a breadth of scope and a boldness missing from most contemporary work.

What I don't understand is why we have history of philosophy as a field of academic research. For those who don't know, philosophers in the English-speaking world have whole careers devoted to researching a particular period in the history of philosophy (almost always within Western philosophy), and sometimes just a single philosopher.

What are these scholars trying to find out? Are they looking for more writings that have been lost or forgotten? Are they trying to trace the historical roots of particular ideas and how they developed over the ages? Or are they perhaps trying to figure out whether particular theories held by historical figures were true or false?

No, not really. Not any of those things. Scholarship in the history of philosophy is mainly like this: there are certain books that we have had for a long time, by a certain list of canonical major figures in philosophy. You read the books of a particular philosopher. Then you pick a particular passage in one of the books, and you argue with other people about what that passage means. In making your arguments, you cite other things the philosopher said. You also try to claim that your interpretation is "more charitable" than some rival interpretation, because it attributes fewer errors, or less egregious errors, to the great figure.

What you most hope to do is come up with some startlingly new way of interpreting the great philosopher's words, one that no one thought of before but that turns out to be surprisingly defensible. It's especially fun to deny that the philosopher said one of the main things that he's known for saying. For instance, wouldn't it be great if you could somehow argue that Kant was really a consequentialist?*

*Kant might actually be a consequentialist -- just a weird kind of consequentialist, who thinks that a good will is lexically superior to (of infinitely greater value than) any mere object of inclination.

2. History of Philosophy Isn't History or Philosophy

Now, let's suppose that you have a really good historian of philosophy, who does a really great piece of work by the standards of the field, which also is completely correct and persuasive. What is the most that can have been accomplished?

Answer: "Now we know what philosopher P meant by utterance U." Before that, maybe some people thought that U meant X; now we know that it meant Y.

This is of no philosophical import. We still don't know whether X or Y is true. You might think that, because the great philosopher thought Y, this is at least some evidence for Y. But that would be extremely weak evidence (almost all of the major doctrines of the major philosophers are false). It would also be a crazy way of going about investigating the issue. It would be much better to just directly consider what philosophical reasons there are for believing Y.

It is also of minimal historical import. "What thoughts were occurring in the mind of this specific person, when he wrote this specific passage?" is technically a historical question. But it is a trivial historical question, unrelated to understanding any of the major events in history. It's not as if, for example, we're going to understand why Rome fell, if only we get the right interpretation of Aristotle's Metaphysics Gamma.

Even when it comes to purely intellectual history, what is historically important is how Aristotle was understood by the people who read him, whether or not what they understood was what Aristotle truly meant.

Historians of philosophy, in brief, are expending a great deal of intellectual energy on questions that do not matter.

You might ask: What's wrong with that? At least the historians seem to like what they're doing, so it's interesting enough to them. True. But intelligent people are a scarce resource in society. It's fine for you to use your brainpower on questions that don't matter. But the rest of society has no reason to pay you for doing that, when there are important questions that society would benefit from having more brainpower devoted to.

3. Why Do We Have History of Philosophy?

Why, then, does this field of academic research exist?

Because research-oriented philosophy departments (like all philosophy departments) have courses in the history of philosophy. When they hire someone to teach these courses, they think they have to hire someone who specializes in history of philosophy. That person will also be expected to do research in addition to teaching, since they are at a research school. So they do the stuff I described above.

A solution: You don't actually need a historian to teach history of philosophy. Any ordinary philosopher can teach history of philosophy, because any ordinary philosopher can read a few major works of the given historical figure, and explain them well enough for undergraduate students. The more complicated, subtle interpretive questions that scholars in history of philosophy debate are not suitable for undergraduate courses. Scholars in history might even be worse at teaching it than ordinary philosophers, since the history specialists are more likely to confuse students by talking over their heads and getting lost in small interpretive details.

So, just hire any philosopher.

4. When History Is Bad for You

The Problem with Religious Texts

Being too focused on history of philosophy is bad for your mind, in something like the way that being overly religious can be bad for your mind.

Religious people are sometimes prevented from looking at and understanding the real world, because of their focus on a religious text. If you take the Bible, the Koran, etc., as a sacred text, then you might try to understand the whole world in terms of it, and thus have an overly narrow perspective. There is also a good chance that the book contains errors or misleading passages, and that the religious person will arrive at false beliefs by trying to rationalize those errors.

Folie a Deux

The great texts in the history of philosophy are not treated quite like religious texts. But they aren't treated entirely unlike religious texts. Historians commonly treat their chosen historical figures with more respect and deference than you would treat any contemporary figure, and probably more than you should treat any human being. They try everything in their power to avoid admitting that the great philosopher was wrong or confused about a major philosophical point.

Almost all philosophers are mostly wrong. But if you spend too much time studying a particular philosopher, you get drawn into a sort of folie a deux, in which you start to perceive the world in terms of that philosopher's ideas. Most historians of philosophy appear to believe that the philosopher they study was basically right (though they do not argue for this in their work, which, as noted above, focuses instead on exegesis).

Prima facie, it's really unlikely that you should be a follower of some philosopher of the distant past (say, over 200 years ago). One reason is that human knowledge as a whole was in a completely different state two hundred and more years ago. Science scarcely existed when most great philosophers wrote. Even philosophy has developed a great deal in the last two centuries. Contemporary philosophers have the advantage of access to earlier philosophers' work, as well as more rigorous training, and fruitful interactions with a very large, diverse, and active group of other professional philosophers.

Now, if your philosophy basically corresponds to that of some philosopher who lived hundreds or thousands of years ago, then you're basically saying that none of the vast expansion in human knowledge that has occurred since then, nor any of the work done by philosophers themselves in the past couple of centuries, is philosophically important. None of that has taken us significantly farther, when it comes to philosophical questions, than some guy who lived in prescientific times.

I think that's super-unlikely.

Please Don't Be an Aristotelian

To give one important example, there are people today who are followers of Aristotle. I think that's crazy. If Aristotle lived today, there is no way that he would be an Aristotelian. If we brought him through time to the present day, he would swiftly start learning modern science, whereupon he would throw out his outdated worldview, and he'd probably laugh at the modern Aristotelians.

Aristotle might have been the greatest thinker of all time. But being a great thinker, even the greatest, is not as important as having access to the accumulated human knowledge of the last 2,000 years. This is why the work of much less-great thinkers who are born today is more likely to be correct than the work of Aristotle. Aristotle's philosophical method is largely about reconciling the opinions of the many and the wise (the endoxa). But of course, those would be the opinions of the people of his day -- who knew next to nothing.

To be a little more specific, Aristotle's philosophy is shot through with teleology. Things are supposed to have built-in goals or functions -- not just conscious beings and artefacts, but everything in nature. This is just a completely false conception of the world. It's not a dumb thing to think if you're living 2,000 years ago. But we now have a vast body of detailed and rigorously tested scientific explanations of all manner of natural phenomena. Natural teleology -- purposes or 'functions' that exist in nature apart from any conscious being's desires -- contributes nothing to any of them.*

*I know that someone is now going to post a comment claiming that natural functions appear in biology. But evolutionary functions are not equivalent to Aristotelian teloi. All biological phenomena are explicable by mechanistic causation.

So if you're still talking about natural functions, I think that's kind of like a doctor who's still worrying about imbalances of the four bodily humors.

Look Outside the Text

Part of the attraction of doing history of philosophy, I believe, is its insularity: one can simply dwell entirely within the world of Philosopher A's texts. You can read all of those texts, and you can know that there will never be any more, since the philosopher is now dead. (Though, admittedly, there will be more secondary literature.)

If you're a regular philosopher, you have to worry about objections and evidence that could come from anywhere. Some philosopher could devise a completely new argument that you have to address. Some scientific development (not even a development in your own field!) could cast doubt on one of your theories (unless, of course, you have carefully defined the questions you talk about so that they are 'purely conceptual'; see previous post).

If you're a historian, you don't have to worry about all that, because you're not arguing that any philosophical thesis is true. You're just saying that some philosophical thesis is supported by the texts. That makes life simpler and easier.

But that is also why history of philosophy is bad for you. Because people actually should think about the big questions of philosophy. And when we think about them, we need to do so in a way that is open to the many different considerations that are relevant to the truth.

We should think, for example, about what is the right thing to do, not what Kant said was the right thing to do; we should think about what is real, not what Plato said was real.