I’m generally sympathetic to deontological ethics, especially rights theory. But some years ago, I discovered this paradox for deontological ethics.*

[* “A Paradox for Weak Deontology,” Utilitas 21 (2009): 464-77.]

1. Background

There is a core type of intuition that drives many deontologists: There are certain ways of harming a person that are thought to be impermissible, even if they would create a larger (but comparable) benefit or prevent a larger (but comparable) harm of the same kind for someone else.

For instance, it’s wrong to murder an innocent person, even if doing so would somehow save two innocent lives. It’s wrong to steal money from someone, even if doing so would let you give twice as much money to someone else. It’s wrong to torture someone, even if doing so would stop someone else from being tortured twice as much.

That isn’t all of deontology, but it is a very important, prominent, and widely accepted part of deontological ethics.

This, by the way, is not supposed to apply to all harms. E.g., some say that it matters whether a harm is aimed at (either as an end or a means) or is instead merely a foreseen side effect of an action. Aiming at harm is said to be worse. Thus, e.g., some think that in war, you can bomb a military target, even if doing so causes collateral damage, as long as the overall benefits outweigh the harms. However, you cannot expressly target civilians (killing the same number of civilians as in the collateral damage case), even if doing so produces greater overall benefits than harms.

So let’s say that a “proscribed harm” is the kind of harm that you’re not allowed to cause, even if it produces a greater, comparable benefit for others. This might involve a harm that is aimed at, or that treats someone as a mere means, or something like that.

2. The Problem

Example 1: Torture Transfer

You’re visiting Guantanamo Bay one day, and you somehow get separated from the tour group. You happen upon a room where two people are being unjustly tortured. Call them P1 (for “prisoner 1”) and P2. P1 and P2 are hooked up to a device that passes a painful electric current through their bodies, causing each to suffer, say, 5 units of pain.

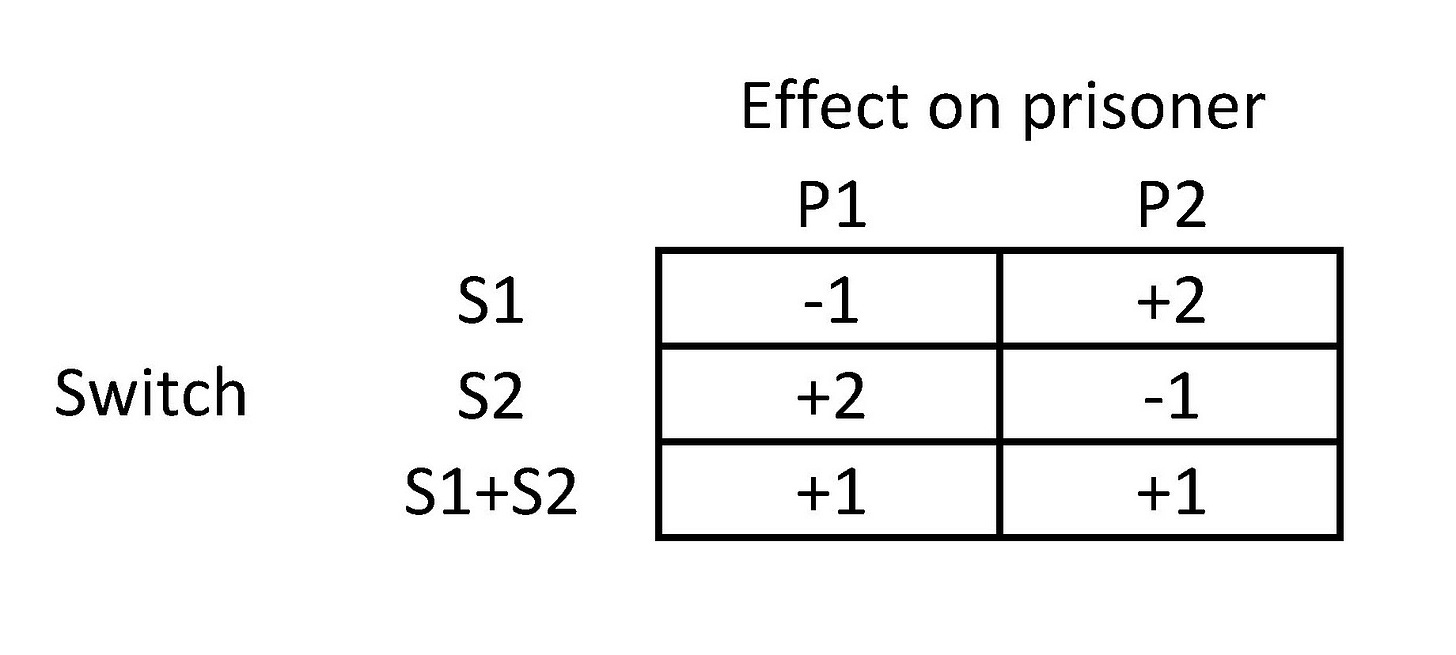

You are unable to release either prisoner, nor can you shut off the machine. However, there are two switches on the torture device, S1 and S2. Somehow, you figure out that if you flip S1, it will increase the P1’s torture by 1 pain unit, but it will also decrease P2’s torture by 2 pain units. If this matters to you, assume that the increase to P1’s torture will serve as a means to reducing P2’s pain (e.g., the switch would not work unless someone was in P1’s chair and receiving an increment in torture). Similarly, if you flip S2, it will increase P2’s torture by 1 unit, as a means to decreasing P1’s torture by 2 units.

Your only options are to flip only S1, flip only S2, flip both switches, or flip neither. See the diagram (negative numbers represent more pain; positive numbers represent relief from pain).

What should you do?

On standard deontological views, it is wrong to flip S1, since this tortures P1 (more), as a means to reducing P2’s torture. Similarly, it is wrong to flip S2.

However, it seems that it is not wrong to flip both S1 and S2, since doing so reduces both prisoners’ torture.

In other words, it looks as if what you should do depends on how you individuate actions: If you look at S1 and S2 as separate actions, both are wrong, so you can’t do either. But if you consider “flipping S1 and S2” as a single action, that action is permissible and perhaps obligatory, since it reduces 2 people’s torture without causing any other harm.

But the permissibility of some behavior cannot depend on our method of individuating actions, since there is no objective fact as to whether “flipping S1 and S2” is really one action or two.

Example 2: Bank Transfer

This is like the previous case, but with theft instead of torture. Say you’ve managed to hack into a bank, and you want to help two bank customers by giving them extra money in their accounts. For some odd reason, you can’t just do this directly. Rather, you have a hack H1 that will steal $1 from customer C1 but simultaneously give $2 to customer C2. You also have a hack H2 that will steal $1 from C2 in order to give $2 to C1. (If you’re worried about counterfeiting or causing inflation, assume that the extra dollar in each case will be deducted from your own bank account, so there will be no change in the total money supply.)

As mentioned earlier, it is wrong to steal from someone, even if doing so lets you give more money to someone else. So it seems that it is wrong to initiate H1. Similarly, it is wrong to do H2.

However, it is fine to do (H1+H2), the combination hack, which merely enriches C1 and C2 by $1 each. (See diagram again.)

Generalization

In general, assume that there is some way of harming a person, such that it’s impermissible to harm someone in that way, even if doing so prevents a greater harm of the same kind to others. Then it seems that you could imagine a collection of actions, each of which taken by itself harms a person in the proscribed way, but where the collection benefits everyone and leaves no one worse off in any respect.

It’s counter-intuitive to say that a set of actions that benefits some people while leaving no one worse off in any respect is wrong. It’s also counter-intuitive to say that each of the individual actions could be wrong, yet the whole set be permissible. So there’s pressure to say that each individual action is permissible, and thus that it is not wrong to harm a person as a means to benefitting someone else by a greater amount.

3. Solutions

That’s it. I don’t have a good solution. But I can’t leave without addressing the most obvious solution you might think of.

The most obvious solution is to modify your deontological theory so that the individual actions are not deemed wrong in the above cases. Thus, we might say that it is wrong to harm another person in certain ways, unless one is also going to perform (or has already performed) another action (or series of actions) such that the set of actions leave the victim no worse off in any respect. This would have the consequence that S1, S2, H1, and H2 are permissible.

Basically, the claim is that it’s okay to do S1 because you’re also going to do S2, and it’s okay to do S2 because you already did S1. So we avoid saying that two wrongs make a right, so to speak, and we avoid giving different evaluations of the behavior depending on how actions are individuated.

Though this is natural on its face, it will force us into some weird implications in other cases. Suppose that you’re in the torture room, as in the Torture Transfer case above. This time, however, you see that someone has already flipped S1. You’re unfortunately suffering from some memory problems, and you can’t remember whether it was you who flipped S1 or someone else. Is it permissible to flip S2?

It’s bizarre to think that it makes a huge difference whether the S1-flipper was you or someone else—that you have to figure that out before you decide whether to flip S2. But that is what our above formulation of deontology implies. (Suppose that you and a friend are both in the torture room, and you agree that you should flip both switches. It would be bizarre to think it makes a big difference whether the same person flips both or instead each of you flips one of the switches.)

Suppose we fix that. We could say that it’s permissible to harm one person to produce a benefit for someone else, as long as your action would be part of a series of actions (by any set of people) that would collectively leave the victim no worse off.

Now imagine that you’re in the torture room again, and you see that S1 has been flipped. But this time, you are unsure whether S1 was flipped by a human being, or instead got flipped by a machine malfunction, or instead S1 just started out in its current position (so prisoner P1 started out getting more intense torture than P2). It’s also quite strange that it should make a huge difference which of these things is the case. (Imagine that you were planning on flipping both S1 and S2, but just as you were reaching out to flip S1, a machine malfunction made S1 flip by itself. It would be bizarre to think that now you can’t flip S2.)

Suppose we modify the deontological principle to agree with that too. Then we wind up saying that it’s okay to harm one person to produce a greater benefit for another person, as long as the beneficiary started out worse off than the victim in the given respect.

But I’m highly confident that it doesn’t matter who started out better off (it’s not the case, e.g., that unhappy people have more stringent rights than happy people).

So a consequentialist would say:

It doesn’t matter (to the permissibility of flipping S2) whether you previously flipped S1 or someone else flipped it.

It doesn’t matter whether another person flipped S1 or a machine malfunction flipped it.

It doesn’t matter whether S1 was flipped by a machine malfunction or just started out flipped.

It doesn’t matter whether one person starts out worse off than another or not.

So it doesn’t matter whether S1 has been flipped or whether the two prisoners are instead in the same situation.

So it’s permissible to flip S2, regardless of whether S1 has been flipped.

With that, we would be abandoning the deontological constraint.

My friend Jay Moss wrote an email to Huemer about this paper:

I recently read your article "A Paradox for Weak Deontology," and I have some issues with the argument you present.

"Torture Transfer" is an interesting hypothetical. It raises some interesting questions about individuating actions, how the moral wrongness of an action depends on the broader "plan" that it's a part of, whether the fundamental unit of moral analysis should be actions vs plans, etc. but I don't think it's a problem with deontology per se. Anyway I would deny the 2nd and 3rd premise.

Adjustment 1 is permissible because it's permissible to violate someone's rights if (1) doing so is necessary to provide sufficient compensation to that person and (2) you actually plan on providing such compensation. For example, let's say that Mary is drowning in the ocean and the only way to rescue her is to knock her unconscious (since drowning victims tend to flail which endangers themselves and the rescuer). In this case, presumably most deontologists would agree that knocking Mary unconscious is permissible because (1) doing so is necessary to rescue her and (2) you actually plan on rescuing her.

Now, the one trick here is the phrase "is necessary". Typically, when we speak of one action being necessary for another action (such as the drowning person example), we're talking about causal necessity, i.e. action X is permissible if X is causally necessary for action Y, where Y sufficiently compensates the "victim". But in the Torture Transfer case, what I mean is moral necessity, i.e. action X is permissible if X is morally necessary for action Y, where Y sufficiently compensates the "victim". For example, let's say that in the drowning case, I can actually save Mary without knocking her unconscious.

However, for whatever reason, I can do this only if I drown 5 other innocent persons (e.g., I know that if I try to save Mary without knocking her unconscious, she will flail so much that I need to steal a flotation device used by 5 other people). Now, in this case, knocking Mary unconscious is not causally necessary to rescue her (i.e. I could just drown the 3 other innocent persons and save Mary without knocking her unconscious).

However, knocking her unconscious is morally necessary to rescue her (if I don't knock her out, then rescuing her [which involves drowning 3 innocents] would be impermissible). Thus, I'm justified in knocking Mary unconscious, because (1) doing so is morally necessary to rescue her (which I'm assuming is "sufficient compensation" for the knockout) and (2) I actually plan on rescuing her.

Adjustment 2 is permissible for similar reasons, except in the reverse. Adjustment 2 is permissible because it's permissible to violate someone's rights if (1) doing so (or at least having had a plan to do so) is necessary to make a previous action morally permissible, (2) the previous action has been performed, and (3) the previous action sufficiently compensates the "victim" for the current rights violation (the compensation came before the harm).

Unfortunately, I think the only hypotheticals that work for this are fairly similar to the Torture Transfer case. But I think the principles themselves make sense. Also I've been speaking of these as examples of permissible rights violations, but you might not classify an action as a rights violation if the "victim" is sufficiently compensated. Maybe, but it doesn't really change the argument much. Also, permitting rights violation so long as there is sufficient compensation isn't consequentialist, since I'm focusing on if the compensation is directed to the same person such that they are better off after the compensation.

Another way around this might be to adopt a kind of two-level deontology, similar to rule-consequentialism. E.g. under rule consequentialism, actions are not the fundamental unit of moral analysis. Rules are the fundamental unit of moral analysis. First, we talk about whether rules are good/bad (in a consequentialist sense). Then, actions would then be judged as right/wrong based on their accordance to the best rules.

You could apply similar reasoning to a two-level deontology. E.g. you might say that it's not actions that are the fundamental unit of moral analysis. Rather, first, we would talk about whether rules or plans or norms are right/wrong in some deontological sense (e.g., a plan might be wrong deontologically if it's execution on net results in the infringement of an individual's autonomy/freedom.

Note that this is not rule consequentialism, since it's not saying that a plan is permissible if it limit someone's autonomy/freedom so long as someone else's autonomy/freedom is promote; rather, it's saying that a plan that involves local limitations on someone's autonomy/freedom is permissible so long as that person's total freedom/autonomy is promoted).

Then, actions would then be judged as right/wrong based on their accordance to the best plans/norms/rules (as judged by the deontological theory). I'm not saying I accept this, but this is something I've thought about before and it doesn't strike me as implausible.

Either way, I think the spirit of the response here is that deontologists don't need to fetishize individual actions in a vacuum in the way that the hypothetical suggests. I don't think there's a good reason to believe that our moral assessments of an individual's actions shouldn't be sensitive to other actions made by an agent (even if those other actions have no causal relevance to the current action) or the broader plan that the agent is trying to carry out. I think any plausible moral theory is going to assess not just individual actions in a vacuum, but rather the collections of actions based on their relation to the broader plan/project that the agent takes to motivate the individual actions.

This is somewhat similar to Kant's point that we cannot judge acts in a vacuum. Rather we should judge the act and the maxim that the agent takes to justify the act. Perhaps a similar point can be said here: rather than just judging an action, we judge the act, the maxim, and/or perhaps the guiding project that motivates the act. And our judgment at each level of analysis can be sensitive to deontological considerations without falling prey to these kinds of hypotheticals.

Dr. Huemer replied:

Some things to think about:

(a) Say we have the principle:

It's permissible to violate A's prima facie rights if (i) one plans on providing adequate compensation, and (ii) the prima facie rights-violation is necessary to provide that compensation.

Is it necessary that A consent, or may one do so without consent? If A must consent, then stipulate in my scenario that A doesn't consent.

Suppose you say A need not consent. Is it permissible for someone (say, the government) to take your house without your consent and destroy it, provided that they later pay you adequate compensation? Assume the compensation exceeds the value of the house, yet you did not consent. This strikes me as impermissible.

You might say that taking the house wasn't necessary to providing the compensation, since the government could have given you money anyway. But suppose that the government gets the money that they're going to pay you with from Walmart, which is paying the government for the land that your neighborhood is on. So they wouldn't have the money unless they were able to deliver the land to Walmart.

(b) Suppose that I perform Adjustment 1 without intending to perform Adjustment 2. (Or perhaps, at the time I do Adjustment 1, I haven't yet decided whether to do Adjustment 2.) This, on your view, is impermissible.

Then, after I perform this wrongful action, I reconsider whether I should do Adjustment 2.

Would this be permissible? It seems that the answer is no, because Adjustment 1 was impermissible, and it will continue to have been impermissible regardless of whether I do Adjustment 2, because I did not have the required intention when I did Adjustment 1. It is counterintuitive that the two actions are now both impermissible.

(c) Suppose that I just performed Adjustment 1, and I can't remember what my intentions were at the time. Is it now permissible for me to do Adjustment 2? It is counter-intuitive that I must figure out what my intentions were in order to know whether I may do Adjustment 2.

(d) A more tangential but interesting point: The scenario is somewhat reminiscent of this version of the Organ Harvesting case discussed by Judith Thomson: Assume the five sick patients are all sick because the doctor deliberately infected them with diseases of different organs. Later, he realized that murder is wrong, so he wants to remedy his mistake. So he comes up with the plan to kill 1 healthy patient and transplant the organs to the five people he infected. Would this be permissible?

Thomson says no (as any deontologist will agree). But note that if he doesn't kill the healthy patient, then the doctor will have murdered 5 people; if he kills the healthy patient, he will only have murdered 1 (since the other 5 will survive). And murdering 1 is surely less wrong than murdering 5. So why shouldn't he kill the healthy patient?

I think this might be relevant, because it seems to suggest that you can't really make up for a rights-violation, or redeem a previous wrong, by committing another rights-violation (even if the latter would compensate the victims of the previous action). At least, that's one way of interpreting the lesson of the example.

Thinking about it, in both situations you are describing, available actions don't seem to cause proscribed harms. In the torture case, one's goal is to reduce the net amount of pain caused, and someone experiencing more pain is an unfortunate side-effect. The bank hack case is similar.

Compare with the trolley problem. In the regular trolley problem, I think it's permissible to switch tracks, and the resulting death is merely collateral damage. However, my intuitions say that if you had to actively push someone onto the tracks to stop the train, that would be impermissible.

Perhaps the difference between those is whether someone's suffering is an accidental effect, or an instrumental part of your goal. Likewise, in the torture case, if only one person was connected to the machine, flipping the switch would have no downsides.

I'm not sure this actually a consistent distinction, but let's suppose so. Then, maybe a thought experiment involving obviously proscribed harms would give us more insight into the problem.

I struggle to think of one though: the generalized example you gave almost seems to rule cases like Organ Harvesting out.

EDIT: re-reading this post, I notice your stipulation about the harm in the torture case being instrumental to increasing the overall welfare. I still think it does not make it a proscribed harm, though.

Consider: normally, murdering another person to save one's life is impermissible. However, if someone credibly threatens to kill you unless you kill another person, I feel like you're at least excused in doing so. The adjusted Torture Transfer case is similar: it's as if a malevolent force pre-arranging this situation for you makes it morally responsible for rights violations caused.