Why We Cancel

Cancel Culture

In a previous post, I explained “why we love evil ideas” (https://fakenous.net/?p=2896).* I think of this as a followup on that: why do people like “canceling” other people?

(*Some people complained that not everyone really loves evil ideas. I suppose I could have titled it “Why belief systems containing very obviously harmful ideas attract more followers than you would expect”, but who would read my blog if it was written like that?)

Some people claim not to know what cancel culture is, or not to believe that it exists. I’m not going to try to give a precise definition, because that’s boring, but here are a couple of examples from the last few years.

Justine Sacco

Justine Sacco was a communications director for InterActive Corp. (the company that owns Match.com, Dictionary.com, and Vimeo). In 2013, as she was heading to visit family in South Africa, she tweeted the following joke: “Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get AIDS. Just kidding. I’m white!” Then she got on her plane.

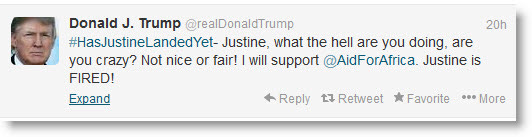

During the next several hours, Twitter exploded with outrage posturing over her “racist” tweet, which became the number one trending topic on Twitter. Ex.:

“In light of @Justine-Sacco disgusting racist tweet, I’m donating to @care today.”

“How did @JustineSacco get a PR job?! Her level of racist ignorance belongs on Fox News. #AIDS can affect anyone!”

“All I want for Christmas is to see @JustineSacco’s face when her plane lands and she checks her inbox/voicemail”

“We are about to watch this @JustineSacco bitch get fired. In REAL time. Before she even KNOWS she’s getting fired.”

Sacco was quickly fired. Later, she apologized for the tweet. The mob succeeded in ruining her life for a few years. She has kept her head down since then. (https://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/15/magazine/how-one-stupid-tweet-ruined-justine-saccos-life.html)

James Damore

James Damore was a software engineer at Google. In 2017, he posted an essay called “Google’s Ideological Echo Chamber” to an internal company message board. The essay argued that the gender imbalance in the tech industry, especially among programmers, could be due to differing interests between men and women, rather than sexism. He also warned that Google was suffering from ideological bias that produced an echo chamber in which dissent was suppressed. Google rebutted this by immediately firing Damore. Enraged critics attacked Damore for his “sexism”. Google CEO Sundar Pichai explained:

“we strongly support the right of Googlers to express themselves … However, portions of the memo violate our Code of Conduct and cross the line by advancing harmful gender stereotypes in our workplace. … To suggest a group of our colleagues have traits that make them less biologically suited to [engineering] is offensive and not OK.” (https://blog.google/outreach-initiatives/diversity/note-employees-ceo-sundar-pichai/)

(Translation: "Of course we completely support free speech, as long as that speech parrots our far-left orthodoxy.") For the Damore essay, see: https://gizmodo.com/exclusive-heres-the-full-10-page-anti-diversity-screed-1797564320. Gizmodo was the first to post Damore’s “anti-diversity screed”. If you look at it, what you’re going to notice is that it is not the least bit offensive or sexist, nor does it remotely suggest that any of Damore’s colleagues are biologically unsuited to engineering, nor is it anti-diversity (it is explicitly pro-diversity), nor is it a screed (it is the most mild-mannered questioning of woke ideology that you could think of).

Etc.

Those are, of course, far from isolated instances. Many instances of cancel culture have appeared over the last several years. If you want to hear more insane cases, try https://www.blockedandreported.org.

What typically happens is that someone says something that is obviously not the slightest bit racist or sexist but that alludes to race or sex in some way that extreme left-wing activists don’t like and claim to find “offensive”. Sometimes, the person didn’t even mention race, as in the case of the professor (Greg Patton) who pronounced a Chinese word that happens to sound like the n-word (https://www.npr.org/2020/09/16/913693813/professor-is-at-center-of-controversy-over-chinese-word-that-sounded-like-racial). Sometimes, the reaction is triggered by someone digging up something that the target said many years ago, as a teenager. In the n-word cases, the outrage is typically triggered by someone’s merely mentioning (not using) the word.

An online mob arises expressing the wildest outrage, as if they just learned that the target person was a serial killer. The mob reacts before they have time to learn the facts of the case, demanding that the target be fired. Often, the target issues an abject apology that reads like the script of a hostage video, but then is fired anyway. Also, often the cancellation target receives threats of violence and may be harassed by “journalists” (as when Sacco was photographed at the airport after landing, or when a New York Post reporter started following her to the gym).

Why do people do things like this?

The Charitable Interpretation

The charitable interpretation is that people are doing what they claim to be doing – that the mobs are people who are very concerned about social justice and equality, that they care about the plight of women and minorities in our society, and that they are trying to combat discrimination.

You can probably guess that I don’t buy that. And you can probably guess why.

First, in most cases, it’s just obvious that the target is not expressing racism or sexism. To accuse them of such generally requires fairly blatant dishonesty. Now, I’m well aware that human beings are capable of a lot of pretty big errors. In my years among the chattering class of society, I’ve heard some amazing falsehoods asserted seriously. Still, the plain factual errors involved in these cases strike me as too much to be accident. It has to be that people are trying to find something to be outraged about. At best, they’re blinding themselves to any non-racist, non-sexist interpretation; at worst, they’re outright lying.

E.g., in the Sacco case, it was obvious from the start that she was making a joke, not seriously asserting that white people are immune from AIDS. She was actually making fun of racism. In the Damore case, people just straight out lied about what he said. In the Greg Patton case, there was no question whatever that he was saying a Chinese word, not the n-word in English, but people still acted outraged and demanded that he be fired (unsuccessfully, though he was temporarily suspended).

Second, what ends could one reasonably anticipate achieving as a result of one of these pile-ons? Suppose you’re deeply concerned about the welfare of women and minorities. How does harassing, intimidating, and trying to ruin the life of Justine Sacco after she made a joke on Twitter, help black people? Try tracing out the mechanism from the Twitter pile-on to … now black people are better off. I submit that it was totally implausible that that would help black people. And because that’s obvious, it’s implausible that the mob was actually trying to help black people.

The Correct, Uncharitable Interpretation

Malice

The uncharitable interpretation: people like to cancel other people because they are malicious. The members of these Twitter mobs are simply terrible people.

Because malice is generally considered socially undesirable, you can’t expect most people to come right out and own that motivation (see the “social desirability bias”). But sometimes, they come pretty close to it, as in the last two quotes from the Sacco case above: “All I want for Christmas is to see @JustineSacco’s face when her plane lands and she checks her inbox/voicemail”; “We are about to watch this @JustineSacco bitch get fired. In REAL time. Before she even KNOWS she’s getting fired.” Those make clear that the writers were taking joy in the thought of ruining someone’s life. They weren’t just regretfully taking up the necessary steps to prevent a greater harm.

You might assume that this is an unlikely interpretation, to be avoided if any more charitable interpretation exists, because presumably most people are not evil. But as explained in my earlier post (https://fakenous.net/?p=2896), we should have no such presumption. Human beings have a natural impulse to hurt and dominate each other – there is tons and tons of evidence of this from history, anthropology, and evolutionary psychology. Not everyone is equally aggressive, of course, but some significant portion of humans are high in aggression. People are also highly tribal, so they tend to feel hostility toward what they see as rival social groups. Which is why in primitive societies, people frequently attack neighboring tribes and try to murder them (especially the men). (https://fakenous.net/?p=2223)

But in our current society, you’re not allowed to just murder people, so we need another outlet for our aggression. That’s why people can take pleasure in ruining other people’s lives. That’s the core explanation.

Ideology

You might think this explanation fails because it doesn’t explain the role of political ideology and why the cancellations are always directed at allegedly racist/sexist/transphobic/etc. people. My account of that: it’s a rationalization. Because although people like hurting each other, they also, at the same time, have at least some small sense of morality and a desire to think of themselves as good rather than evil. So normally, you would feel some sort of guilt or shame after ruining someone’s life, if you’re a normal (non-psychopathic) person.

So what people often do is to cook up moralistic rationalizations for harming others. If we can invent some story about how the people we’re harming are “the bad guys”, then we get the best of both worlds, so to speak: we get to feel self-righteous while simultaneously indulging our primitive impulses to hurt and destroy.

Witch hunt signaling

Then of course there is the standard witch hunt dynamic. If your village is conducting a witch hunt, you’d better denounce some witches; otherwise, people will start to suspect that you’re a witch. If the witch hunters are winning, you want to position yourself as on their side. So even if almost everyone knows that the whole thing is bullshit, you can still get most people pretending to be concerned about witchcraft, to show that they are with the witch hunters and not the “witches”.

You might think online communities are different because you can easily leave such a community if they're acting crazy, whereas it is much harder to leave your real community. However, it seems that many people are emotionally attached to their online communities. Our tribal instincts get triggered by these pseudo-communities, making us (wrongly) feel that we need to stay and seek status in them, however toxic they might be.

Hurt and offense

A corollary of the above is that I don’t take seriously people’s claims to be psychologically damaged by words that were obviously not meant in a hostile way. E.g., in the Patton case, a group of students wrote a letter complaining about their trauma: “We are burdened to fight with our existence in society, in the workplace, and in America. We should not be made to fight for our sense of peace and mental well-being at Marshall.” Talk about drama queens.

I don’t believe that anyone was traumatized by hearing that word. Rather, I believe those kids wanted the feeling of exerting power over their professor. The cheapest way to seize power in American universities is to claim to be harmed by someone’s words, or accuse someone of racism, sexism, etc.

Conclusion

Don’t fall for the cancellers’ posturing. They haven’t been hurt, they don’t care about justice, and they’re not trying to help anyone. They’re trying to hurt and dominate other people.